I was there, once upon a time, long ago

View(s):Concluding our series of well-known Naturalist Rex I. de Silva’s memoirs ‘From ocean depths to the stars’

Night in a watch hut

I once spent a moonlit night in a cultivator’s watchhut. I hoped to encounter a cross-section of the wildlife inhabiting the area. Disappointingly, apart from a few wild boar, there was not very much to see or hear, apart from the snorings of my companion. Nevertheless an army of “creepy crawlies” explored me, and I spent much of the night alternately slapping or scratching various parts of my anatomy.

Floods

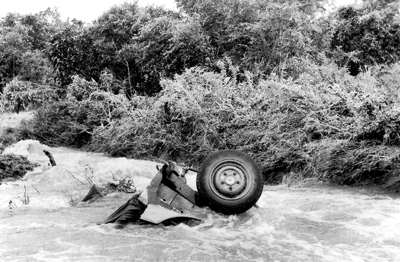

December 1957 saw the heaviest rains on record in the Eastern Province. The Senanayake Samudra spilled over for the first time since completion of the dam. There was severe and large scale flooding leaving hundreds marooned, many in the jungles.

This Land Rover was swept off the road by flood waters near Kondawattawan. December 1957 (Plate 6).

The Navy, Police and a unit from the U. S. Navy Seventh Fleet mounted rescue operations, and additional boats were made available by the Gal Oya Development Board (GODB) for volunteers to assist in the rescue operations. Bevis and I joined one of these groups.

Due to the high water levels we were able to take the boats into the jungles from where we rescued several people. Some who had climbed trees to escape the floods gave us anxious moments as their arms and legs had “frozen” in position and it caused them extreme pain when their limbs were moved in the rescue efforts.

Much worse affected was the wildlife. Over one thousand wild boar were drowned, together with a smaller number of deer. Elephants were unaffected by the floods which apparently also did not have a noticeable effect on leopards and bears, judging from the absence of corpses. A few unscrupulous individuals started to collect carcasses of the drowned wild boar and offer them for sale, until the Police intervened to stop the practice, but not before a large number had been sold.

Veddahs

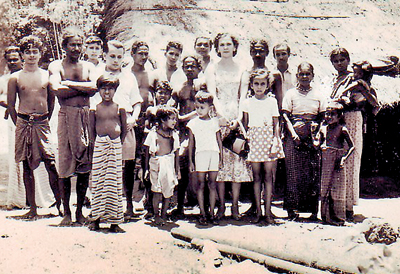

My interest in Veddahs was first aroused when a school teacher began to read to us from Dr. R. L. Spittel’s books Savage Sanctuary and Wild Ceylon. She was obviously a great admirer of Dr. Spittel and her stories fascinated my nine year old mind. I hoped that someday I would meet these Veddahs and learn more about them. One can imagine my excitement when my dreams came true some years later and my family moved to Amparai in the Gal Oya Valley. The “Valley” included most of the hunting grounds of the Bingoda Veddah clans (plate 10).

Mullagama in the mid 1950s: Kaira (3rd from left), Gama? (6th from left), the writer (7th from left), Handuna at my left shoulder, my mother (next to Handuna) and Poromala at her left shoulder. (Plate 10)

When the Senanayake Samudra began to fill many of the Veddahs living on the future reservoir bed were temporarily relocated to Mullagama. Shortly after, the area surrounding the Senanayake Samudra was declared a protected area (the Gal Oya National Park) and Veddah families living there were also moved to Mullagama.

The village was divided into two parts; the prosperous Sinhala village surrounded by lush groves of oranges (Pani dodang) and separated from it by a stretch of fallow land was the poverty stricken Veddah village.

In the 1950s there was no road to Mullagama; just foot paths and a cart track and I estimate that the distance from my home to the village was around 12 miles or so.

I frequently walked to Mullagama from my home. Sometimes, if I was lucky, I would meet a friendly carter who would give me a lift part of the way. One memorable journey was on a full-moon night where the forest was all silver and black, as beautiful a sight as one could imagine.

But beauty also concealed the beast so I went armed mainly for protection against bears. Many village hunters applied a little chunam (lime paste) on to their foresights for improved shooting at night. Not having access to chunam, I applied toothpaste on my gunsight but never had occasion to use it in this manner. On reaching Mullagama I would settle in the little one-room school house which never seemed to be in session. There Kaira and I would plan the day’s activities. After a day or two I would walk back home. It was thus I learnt of the jungle and its inhabitants.

The writer’s father, Ian M. De Silva, one-time Chairman of the Gal Oya and River Valleys Development Boards, Honorary Deputy Director of the Department of Wildlife Conservation and Honorary Secretary of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society

Gal Oya valley was once the haunt of the Veddah outlaw Tissahamy (aka “Meenimaruwa”) who was made famous by Dr. R.L. Spittel in his book “Savage Sanctuary”. Tissahamy died and was buried on August 26, 1952 at the Badulla cemetery. A tombstone, courtesy of Dr. R. L. Spittel, marks his grave. Some of the Mullagama Veddahs were contemporaries of Tissahamy and knew him well although it was obvious that many disliked him. All the Veddahs whose images are depicted here were from the Bingoda clans. (For convenience I have subsumed those from Danigala, Rathugala, Walimbe, Henebedda etc. with the Bingoda Veddahs). The outlaw Tissahamy (who was actually half-Veddah) was also of Bingoda stock. In more recent times there have been other Veddahs bearing the name “Tissahamy”. These individuals are sometimes confused with the famous outlaw. The Veddahs I knew were simple folk struggling to survive from day-to-day. They had not achieved the celebrity and political status enjoyed by their (putative) descendents the Wanniya Laetho of today.

There has, rather unfortunately been some misinformation in the media regarding the Veddahs. One documentary (sic.) claims that Veddahs lived in caves until 1985. This is incorrect. Veddahs lived in caves in the nineteenth century and early part of the twentieth, but by the 1940s the last of them abandoned caves and lived in wattle and daub huts. Caves were however used as temporary camps by hunting parties until the 1960s or so.

Another “documentary” shows Veddahs going on the hunt wearing skirts of leaves. To the best of my knowledge no Veddah ever wore such garments, except possibly, in some of their religious ceremonies. A question which has been asked repeatedly in recent years is “Are there any genuine Veddahs left in Sri Lanka, and what is the status of the modern Wanniya Laetho (aka Wannila Aththo) vis-a-vis the Veddahs of yore”? Opinions differ and I do not know the answer but I look forward to a resolution of this question.

The Sri Lankan Veddahs have been studied by scientists and scholars for at least 150 years. Reliable information on these interesting people has been published by Dr. R. L. Spittel, Gamini Punchihewa, the Sarsin brothers, Seligman, Nandadeva Wijesekera and others.

In the mid-1950s Kaira and most of the other Veddahs hunted with decrepit muzzle loaders. An occasional bow and arrow could be seen, but these were mostly ornamental. All the Veddahs I knew were poor shots with the bow and arrow.

Pellet bows were another thing and many Veddahs were skilled in their use. These could be used for killing small game and birds, but their prime purpose was to scare pests away from their meagre crops. (A pellet bow is a short bow with two parallel strings and a pouch set midway. It fires stones.)

Jungle Tide

John Still, author of “Jungle Tide” considered the jungles of Sri Lanka to be comparable to an ocean tide, which retreats when civilizations expand and returns to reclaim its earlier domains when civilizations decline.

The Sri Lankan jungle tide has now retreated farther than ever before. Will it return to regain its lost domains, or has the tide retreated to the point of no return?

Epilogue

The writer’s father’s Rolleicord 5a which is still in good optical and mechanical condition.

I was privileged to have known the Sri Lankan jungle when it was still vigorous and thriving.

I have shared in the lives of its people and creatures and learnt how to survive in the wilds. In my reveries I see a beautiful tank surrounded by jungle, at one margin of which is a wide glade.

The ground is marked with the footprints of water birds: wild boar have recently dug the earth for roots and tubers and crossing the glade are the hoof prints of spotted deer. In the midst of these are the footprints of an elephant and the miniature ones of her baby.

In my mind’s eye I also see a sunburnt youth (plate 7); his cloth hat is battered and he wears canvas boots with holes in them, his khaki shirt has obviously seen better days and one trouser pocket bulges with shotgun cartridges.

He carries an old shotgun and walks slowly with eyes directed to the ground: he is reading the stories that the tracks tell.

Yes; I was there, once upon a time, long ago.

We left Gal Oya in 1960. I never hunted again.

“I am glad that I shall never be young without wild country to be young in” (Aldo Leopold)

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus