Giving life to little hearts

View(s):A joint Lady Ridgeway Hospital -British team of heart specialists take a giant step in the annals of paediatric cardiology in Sri Lanka.

Kumudini Hettiarachchi and Shehani Alwis report

Two mothers from far apart as Talawakelle and Jaffna. Both have been spending their time anxiously at the Lady Ridgeway Hospital (LRH) for Children in Colombo. Now the smiles come easily – no more worries because where there was despair, there is hope.

For Padmarani who supports her family by plucking tea in Talawakelle, life came to a standstill when her nine-year-old daughter Theresa Mary was diagnosed with a major heart issue.

Dr. James Gnanapragasam

Rheumatic fever being the culprit, the danger signals that Theresa was very ill, were apparent. She was having chest pain and shortness of breath and would also faint often.

While humble Padmarani may not have realised the gravity of her daughter’s condition, what she also did not know was that Theresa (pictured above) would become a trailblazer in Sri Lanka. She would be the first in the country to undergo the Ross procedure under the hands of a joint LRH-British team of heart specialists.

Theresa’s vital aortic valve had been affected and she could suffer congestive heart failure, due to blood flowing back from the aorta to the left ventricle. To save her life what was needed was the Ross procedure or pulmonary auto-graft, considered the “top-end of paediatric cardiology”.

This is just what Paediatric Cardiac Surgeons Dr. Iresh Wijemanna, Dr. Mahendra Munasinghe and Dr. Kanchana Singappuli from the LRH supported by Paediatric Cardiologists Dr. Duminda Samarasinghe and Dr. Shehan Perera working in tandem with Paediatric Cardiologist Dr. James Gnanapragasam, Paediatric Cardiac Surgeon Dr. Markku Kaarne and Paediatric Intensivist Dr. Iain MacIntosh from the Southampton University Hospital in the United Kingdom did.

Having performed 10 complex operations–including the Ross procedure on Theresa– during their visit in March, Dr. Gnanapragasam tells MediScene that unlike other teams which fly in from abroad for a quick mission, they were hoping to leave a legacy by working with the LRH doctors to expand as well as strengthen their expertise and skills.

“Surgical operations cannot be learnt from books but through practice and careful observation. We focused on selected cases that are complex and have not been performed in Sri Lanka before,” he says. Before MediScene gets an insight into what the Ross procedure is, a “lesson” on the heart comes from Dr. Gnanapragasam.

Pointing out that a person’s heart would be the size of his/her fist, he urges us to visualise the heart of a baby. In our minds’ eye we see the tiny heart of a newborn, bringing home the reality of how delicate any procedure on such an organ would have to be. To add to the complexity, heart specialists “can never operate on the working or beating heart. While the operation is being carried out the heart has to be externally supported by machines. This process indeed is really stressful to the heart,” he says.

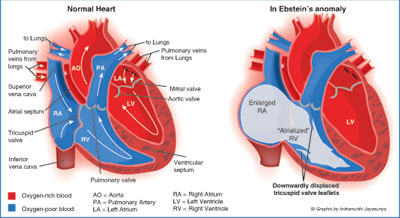

The heart has four chambers, he says, explaining that usually when the oxygen-poor blood from all over the human body comes to the right atrium, it is sent down to the right ventricle and pushed through the pulmonary artery to the lungs where it exchanges the carbon dioxide for oxygen. This is the blood which returns to the heart, but this time to the left atrium, onto the left ventricle, with the aorta then taking the oxygen-rich blood to all parts of the body.

Under the Ross procedure (developed by British surgeon Dr. Ronald Ross way back in 1967), Theresa’s defective aortic valve was replaced by her own pulmonary valve while a substitute bovine valve (bovine homograft) replaced the latter, says Dr. Gnanapragasam.

Stressing the need to be meticulous when dissecting the pulmonary valve to prevent damage, he pinpoints the advantage of this procedure as against the replacement of the aortic valve with a mechanical or tissue valve. Being similar to the child’s own aortic valve in shape, size and strength, the pulmonary valve would do away with the need to replace it as the child grows up, MediScene learns. Another benefit would be that lifelong blood-thinning medication (essential if a mechanical valve is inserted) and its risks could be dispensed with.

Meanwhile, for Alaharani’s son Nisarujan, 14, from Jaffna it was the tricuspid valve that was causing heart trouble. Breathless and panting after climbing even a short flight of steps and always tired, the hospital rounds had begun for them seven years ago, disrupting the family’s home routine and work schedule.

Nisarujan was a victim of a rare and serious abnormality of the heart — Ebstein’s anomaly, a problem with the tricuspid valve.

The tricuspid valve regulates the one-way flow of blood between the right atrium and the right ventricle while the mitral valve does the same job for the left side of the heart, MediScene learns. Giving the tricuspid its name, this valve has three leaflets or cusps – septal, anterior and posterior. The septal is the smallest and is attached to the fibrous ring of the valve.

But in Ebstein’s anomaly, a congenital heart defect (present from birth, the cause of which, whether genetic or environmental, has not been established yet) the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve is not in the right position but displaced towards the apex of the right ventricle of the heart.

In its wake would come a severe valve leak, with blood flowing back into the right atrium from the right ventricle. The atrium would also get enlarged, MediScene learns. This leads to the malfunctioning of the heart and would cause fluid to build up in the body. If not treated, heart failure may be the end result.

It was to meticulously detach the tethering of the tricuspid’s septal leaflet that Nisarujan underwent complex surgery which Dr. Gnanapragasam calls “a kind of tailoring in a way, an art”.

The local and foreign team performed an adapted ‘cone procedure’, folding the extra tissues on the enlarged right side of the heart while reshaping the tricuspid into a cone. Then the valve opens to allow the blood to flow through from the right atrium to the right ventricle, after which it closes by linking up the leaflets.

Commending the LRH heart doctors for work well done in Sri Lanka, Dr. Gnanapragasam says that there has to be expertise to diagnose that an artery has taken an unusual bend rather than just observing that the artery is missing. “Such a diagnosis would slip by quite a lot of doctors,” he says, adding that another step in the right direction was the surgical documentation being scrupulously maintained at the LRH.

Consultant Anaesthetists Dr. Anoma Perera, Dr. Rupika Mahalekama, Dr. Mithrajee Premaratne and Dr. Dakshi Jayawickrama not only supported the surgeries but also handled the critical after-care in the ICU. Running parallel with the surgical programme was another in the Cardiac ICU with Dr. MacIntosh, benefiting the children coming from all over the country.

Plea for cadaveric donation

Why import very expensive valves necessary for heart operations in babies, asks Dr. Gnanapragasam, urging Sri Lanka to put in place a cadaveric donation system to help save lives.

This donation process is happening for corneas and kidneys, so why not for heart valves, he says, requesting that a tissue bank be set up. “This is an essential step in the future.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus