News

Sterile males to tackle war against dengue

The latest weapon that Sri Lankan authorities are to brandish against the deadly dengue-carrying female mosquitoes is sterile males. The Sterile Insect Technique to prevent mosquito breeding is to be introduced next year (2014), the Sunday Times learns.

Tests being carried out

Under the ‘Sterile Insect Technique’, laboratory-bred male mosquitoes which have been rendered sterile through irradiation will be introduced to the environment to mate with female dengue mosquitoes in the wild, said Prof. W. Abeyewickreme, Professor in Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya and Chairman of the Industrial Technology Institute (ITI) who is coordinating this programme.

Such mating will not bring forth any larvae, he pointed out. This programme is being carried out by the Molecular Medicine Unit of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, the Anti-Malaria Campaign (AMC), the ITI and the Atomic Energy Authority (AEA) in collaboration with Austria’s Insect Pest Control Laboratory in Seibersdorf.

The Sunday Times understands that along with Sri Lanka, countries such as Pakistan, Thailand, the Philippines and China will also implement this technique to fight dengue.

Explaining that the dengue vector is Aedes aegypti in urban areas and Aedes albopictus in semi-urban areas, especially in natural breeding habitats such as plant axils, Prof. Abeyewickreme says they have already established an insectary and mosquito-rearing facility at the AMC’s Entomology Unit.

Having adequate numbers of mosquitoes now, the Sri Lankan team is in the process of “sexing” them, through ‘mechanical’ and ‘behavioural’ approaches for sex separation.

Going into technical detail, he said the ‘mechanical’ separation possible at the pupal stage will include: Sieving methods using standard sieves; Fay-Morian glass plates sex separation systems with required modifications; and adjustable opening separation systems.

‘Behavioural’ separation is possible at the adult stage due to the blood-seeking behaviour of females, it is learnt. In these two Aedes species, the female mosquito feeds on blood while the male mosquito feeds on nectar. Once the “sexing” is done, the male mosquitoes will be sterilised by irradiation, according to Prof. Abeyewickreme, who explains that the pupa will be put into chambers and exposed to X-rays or Cobalt 60 rays at the AEA. The separated female mosquitoes will be destroyed.

Thereafter, the sterile male mosquitoes will be let loose to mate with the female mosquitoes in the environment, the result of which will be non-viable progeny.

Reiterating that the fight against dengue should be multi-pronged, Prof. Abeyewickreme quoted the findings of a five-year cross-site research and capacity-building programme between 2006 and 2011. The six countries which were part of the study were Sri Lanka, India, Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines.

This study on ‘Eco-Bio-Social Research on Dengue in Asia’ states: “……..The evidence generated suggests that vector management would be more sustainable when involving several partners including local communities; that targeted water container interventions achieve a significant reduction of dengue vectors (in India, Thailand, Sri Lanka and Myanmar); and that novel non-insecticidal intervention tools (such as rectangular water container covers in India, sweeping nets or dragonfly nymphs in Myanmar and copepods in Thailand) could well complement or replace other interventions.

“The prospects of a forthcoming dengue vaccine and — if ethically sound and acceptable by society – the use of genetically-modified vectors will add further tools for finally achieving a more comprehensive prevention of dengue virus transmission.”

With regard to the development of a vaccine, Prof. Abeyewickreme is quick to point out that even when he was a medical student the promise was that a vaccine would be developed in five years. More recently, at the conference on ‘Dengue: The Way Forward’ organised by the Health Ministry in Colombo on October 16, Prof. Duane Gubler who is the Founding Director of the Signature Research Programme in Emerging Infectious Disease at the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore also promised a vaccine in five years.

The “five years” have been a long time in coming, says skeptical Prof. Abeyewickreme, adding that it has been a perennial promise. This is why a multi-pronged approach is necessary to fight dengue, he stresses, pointing out that an integrated programme which includes vector control, community mobilisation and household level waste management as well as good clinical management of dengue patients in hospitals is vital.

Can we be happy with the present situation, he asks, underscoring the importance of vector control. The vector in the case of dengue being the Aedes mosquito, we see an adaptation by them to the environment as well as the dengue virus, he says.

Taking the environment as an example, he adds that although the Aedes mosquitoes usually breed in clean water, there is evidence now that they also breed in polluted water.

While Aedes aegypti the main vector is a container-breeder, the other vector, Aedes albopictus, breeds in natural habitats such as ornamental plants and also in economic plantations like banana and pineapple. Can we ask people to destroy crops that bring an income to them, he asks, pointing out that the only way is vector control.

Dealing with community mobilization, Prof. Abeyewickreme cites an intervention in the Gampaha district from February 2009 to February 2010, that the Faculty of Medicine, Kelaniya University, carried out with the support of the WHO’s Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

The results had found that the coordination of local authorities along with increased household responsibility for targeted vector interventions with regard to solid waste management is vital for effective and sustained dengue control.

Tie-up sought with UK based Oxitec

Discussions have been held with Oxford-based Oxitec on collaborations in the development of the Sterile Insect Technique in Sri Lanka, said Prof. W. Abeyewickreme. It is better for us to develop this technique among our mosquitoes rather than bringing in a strain of mosquitoes from another country, he said.

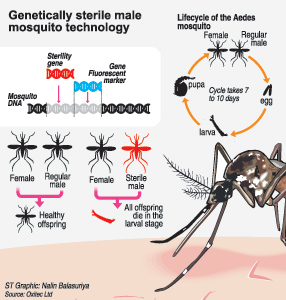

Oxitec has developed a genetically-sterile male mosquito technology which can eliminate the dengue vector, the Sunday Times learns. It is better not to import a foreign strain as in the Sterile Insect Technique, after mating with mosquitoes in the wild only about 85% of the lab-engineered males die, said Prof. Abeyewickreme. “There is the possible danger of the balance males (14.5%) mating with females in the wild and producing a new strain with a different genetic make-up.”

We have asked Oxitec whether we could get their collaboration in training our staff, he said, adding that a concept paper has already been submitted to them through their local partner Omega Global Pte Ltd. Citing an example of how mosquitoes from Oxitec which is in the United Kingdom could differ from those in Sri Lanka, ITI’s Medical Entomologist Dr. Nayana Gunathilaka of the Biotechnology Unit said the “swarming levels” could be different.

Sri Lankan mosquitoes can fly up to gutter-level or even higher elevations and those from Oxitec may not be able to do so because they come from a different geographical region. However, a gene-mix of our higher-flying mosquitoes and those imported from the UK may cause trouble, he says.

Last week, when the Sunday Times met Oxitec’s Field Studies Director Dr. Kevin Gorman, he described the technique they have designed to bring mosquito numbers down as “something new, safe, friendly to the environment, sustainable and affordable”.

Referring to a small, four-month “demonstration trial” among 2,000 people that Oxitec carried out in the Caribbean’s Cayman Islands in 2010, Dr. Gorman said it reduced the mosquito population by 80% within four months. Rearing the mosquito in a laboratory in the Cayman Islands with eggs sent from the United Kingdom, he said they separated the males from the females in the pupa stage through manually-operated machines. These males carry a lethal gene and a marker gene. When the males are released into the wild, they go looking for the females and mate with them. When the eggs that the females lay thereafter hatch, the progeny die as larvae or pupa.

After such releases, mating and death of the progeny, the next generation of mosquitoes in the wild is smaller. The marked males having performed their duty also die after three days, said Dr. Gorman who was in Sri Lanka to attend the Dengue Tools Consortium sponsored by the European Union.

When asked about the risks, he said it was self-limiting technology. The male mosquito does not take blood-meals from humans but feeds only on nectar, so there is no contact with humans. Usually, an “inevitable impact” when controlling a pest is that there comes about an ecological niche or hole.

But Aedes aegypti is an invasive species, not a native. When invasive species come in, they push out native biodiversity. “If however, we get rid of the invader, native biodiversity could bounce back to fill that niche,” he added.Pointing out that the programme has been a success in Brazil, Dr. Gorman said there are deliberations and assessments currently being carried out in India, Panama and the United States of America.

comments powered by Disqus