Making magic in the museum

My conversation with Sir Roy Strong–who last month delivered a lecture in Colombo on “Shakespeare’s Gardens’ as part of the run-up to the Fairway Galle Literary Festival to be held in January–is sprinkled with fact checking and cautious corroboration.

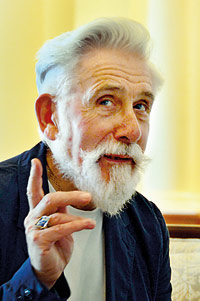

Sir Roy as Charles I based as the painting by Sir Anthony Van Dyke. Pic by John Swannell

There are snippets of information which are seemingly incongruent with the snow-haired gentleman with heavily lidded eyes and well-manicured beard sitting across me. Does he really ride a tricycle? Why a tricycle and not a bicycle? Was his 75th birthday gift to himself a personal trainer?

Was his 80th birthday project really a photography series recreating his favourite famous historical figures? Sir Roy receives the questions with an unflappable expression and a piercing twinkle in his eyes.

Now aged 80 and travelling through Sri Lanka, his penchant to blaze through stereotypes is a lingering trait of his early years and he’s used to the incredulity of strangers.

Years ago, an 18-year-old Roy Strong wrote a letter to his teacher professing a desire to one day become the director of the National Portrait Gallery in London. Like most adolescent ambitions, it was perfunctorily written and then forgotten.

The letter was resurrected when he actually did become the youngest director of the National Portrait Gallery at the age of 32 and then six years later, went on to become the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

A product of the 1944 Education Act which opened up possibilities of financial support and scholarships for those unable to afford it, Roy Strong was in the company of many renowned figures of the period who used their education as a vaulting pole, going on to become crucial figures in Britain’s cultural scene.

His mother in particular, took pains to make sure that her three sons were educated. “It was a magic period where you can actually ascend.

And I got there – but I always knew what I wanted to do,” reminisces Sir Roy. “I was director of the Portrait Gallery at the age of 32 and a director of the V&A( Victoria and Albert Museum) – not keeper of a department – at 38.

And that, in its turn, presented problems because you have everything you’ve dreamed of at a very young age and then you have to think ‘well, what are you going to do with the rest of your life?”

The National Portrait Gallery that Sir Roy inherited during his directorship was a dreary one and the cultural prognosis – hampered by the post-war climate – was bleak.

Shaking the establishment out of its apathy and contending with the austere post-war atmosphere which hung over Britain was going to be a daunting task.

Out of sync with the common man, London museums of the sixties had all of the severity and deference but none of the warmth.

With dwindling finances (Sir Roy had to axe an entire department at the Victoria and Albert and also began to charge admission fees – both moves drawing much criticism) and unusual commissions and acquisitions (exhibits like paraphernalia belonging to the Beatles for instance or Annigoni’s 1969 severe portrait of the Queen), Sir Roy kept pushing both establishments out of their cultural comfort zones and leaving his mark on London’s cultural scene.

Before his tenure, photography was not permitted in the National Portrait Gallery and neither were portraits of living people. Later at the V&A, he managed to prise the museum out of the clutches of the Department of Education, allowing it to raise funds privately and giving it more control over staffing and acquisitions.

“I was an unusual museum director. I brought a high sense of theatre and excitement,” reflects Sir Roy. “I’ve always been loyal to the idea of museums being monuments to scholarship but they’re also monuments of communication to a very wide audience.”

Looking back, he notes that his dual approach to curation was integral in his profession – “You must lift the public to paradise and excite them but you must occasionally do things which also claw at them”.

There’s a mourning ring on his fingers – jade green inscribed with Sir Roy’s coat of arms and the initials R and J intertwined with them.

Sir Roy Strong in Colombo: Taking museums to a wider audience. Pic by Indika Handuwala

While he carries around this reminder of his late wife, Julia Trevelyan Oman, in Herefordshire lies a horticultural monument of love, bearing witness to their 32-year marriage.

These days, Sir Roy’s greatest source of contentment, is The Laskett, the four acre garden that he and his late wife, once tended to.

When Sir Roy and his wife purchased the house and garden, they surveyed the vast space with its three-feet high grass and untended fields with dismay. Julia had a knack for design and gardening but Roy was indifferent to it.

Within a few weeks however, what began as a ‘gigantic folly’ soon became a deeply personal labour of love between both husband and wife who tended to it for three decades.

Inspired by Italian gardens like the Villa Lante and by those of Tudor and Stuart England, the garden grew to be an extension of both husband and wife.

As for the answers to my questions – Yes, Sir Roy keeps fit on a racing tricycle. “Never had a bike as a child, and I can tell you, you can never learn balance at 77,” he solemnly informs me.

This year’s photography series with John Swannell combined Sir Roy’s twin interests of dress and history and depicts Sir Roy being transposed into different historical roles, channelling the personalities of Henry VIII to Rasputin and Emperor Augustus.

Although not intended to mark his birthday, it coincided with his 80th birthday and was a timely photography project.

Before we wrap up our conversation, Sir Roy mentally maps out his plans for the year ahead. There’s a book on Shakespeare’s gardens and the second volume of diaries to be published next year and also an exhibition of his clothing on display as well.

For now, he’s interested in his travels around Sri Lanka, “I think the important thing when you’re older is to always have new projects.

And this is why I come to a place like Sri Lanka or I take people to India. I’m reading and learning about things that I knew nothing about. I’m not going over things I’ve done for years and Sri Lanka is a voyage of excitement.”