News

Rural lad with a childhood passion for animals turns researcher on jumbos

Ashoka demonstrates to some youth in Dahaiyagala how to set a night-vision camera.

Two researchers in a jeep in the dead of night in the jungles of Uda Walawe – one is fast asleep and snoring loudly, but the other is awake, peering into the darkness.

Suddenly there looms a darker-than-the-night shape, very close to their vehicle. Closer it comes, 50m away but drawing still closer. Bleary-eyed Ashoka Ranjeewa, 34, may be, but he realises the danger. He is in a quandary — should he wake up his friend and stop him from snoring loudly?

There is no time for a decision, for the huge, wild elephant is upon them and Ashoka too pretends to be asleep, although through slit-eyes he watches the pachyderm.

Just one foot away from the jeep, the elephant stops short, looks inside, takes a whiff of this strange thing, raises his trunk and walks away into the Dahaiyagala corridor in close proximity to the Uda Walawe National Park (NP).

A moment of danger, but this elephant is no stranger to Ashoka who was engrossed in the study of the human-elephant conflict (HEC) last year. It was an elephant he had dubbed ‘155’, when he was immersed in another study within the Uda Walawe NP back in 2007.

“Then we thought it was a ‘seasonal visitor’ seen once or twice a year,” says Ashoka, explaining that the elephant was once again spotted near the fence of the park bordering the Tanamalwila Road, awaiting tasty morsels such as fruit and kitul branches from passers-by in 2009.

When the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) put up a second fence to prevent the elephants from seeking hand-outs, ‘155’ disappeared, only to be found much later splattered with gunshot wounds which the DWC veterinary surgeons treated.

Ashoka noting details of a house damaged by elephants in Danwel-odaya.

The midnight rendezvous with ‘155’ last year made Ashoka look at the many photographs he had taken of this elephant back in 2007, with the realisation dawning that once the feeding at the fence ended, he had most probably gone into crop-raider mode.

For Ashoka, elephants are not an acquired passion, but creatures which fascinated him even as a child. With his home being 500-600 metres from the border of the Uda Walawe NP, even as a boy of about four he was used to seeing elephants in his garden. “Their footprints amazed me and their size left me stunned,” he says, also quite familiar with the HEC.

While his education was at the Godakawela Kularatne Central College, his basic Degree in Social Sciences he obtained from the Sri Jayawardanapura University, followed by a Master’s in Environmental Sciences from the Open University.

In the gap between the Advanced Level examination and admission to university back in 2001, he worked as a Research Assistant studying the ‘Mobility patterns and habitat use of the identified Uda Walawe Park elephant population’, getting to know many of them closely.

After his degree, it was a stint as a journalist, reporting on environmental issues. It was then, trapped in the asphalt jungle that is Colombo, that he wondered why he should not return to his village and engage in the work he loved.

Ashoka goes back to his study of elephants at the park – there are about 800 to 1,200, he says, and he can identify around 350 adult cow elephants and about 400 mature bulls.

When asked, he explains that their shapes and their ears are the clue to their identification and he has not only given names but also numbers for some of his favourites.

Cow-elephant Amali knows him very well and whenever the jeep he is in parks close to her, not a glance does she cast his way, even though she is with her baby. However, when another jeep attempted to do the same, she was quick to show her displeasure, bypassing his vehicle to charge the intruder.

Then there is the handsome bull elephant ‘141’ in very good shape. There are little de-pigmentation patterns on his ear-lobes, says Ashoka, explaining how the males are able to suppress their musth whenever there is another dominant male around.

Pointing out that some bulls pay a visit to the Uda Walawe Park when they are in musth, he says that there are others whose home is the park, be it the dry or wet season.

Ashoka should know because the research for his Master’s revolved around the “unique phenomenon” of bull-elephant groups. Sometimes finding 8-10 stud bull-elephants together, he was curious to get some answers. Were they permanent associations or just random cliques?

A social network analysis by him found that the bull-elephants got-together randomly. But he had his suspicions that these random groups were formed to raid crops in the villages bordering the Uda Walawe NP.

This and much more became his next project which he carried out last year, expanding to gather information from where the seasonal males came from once a year.

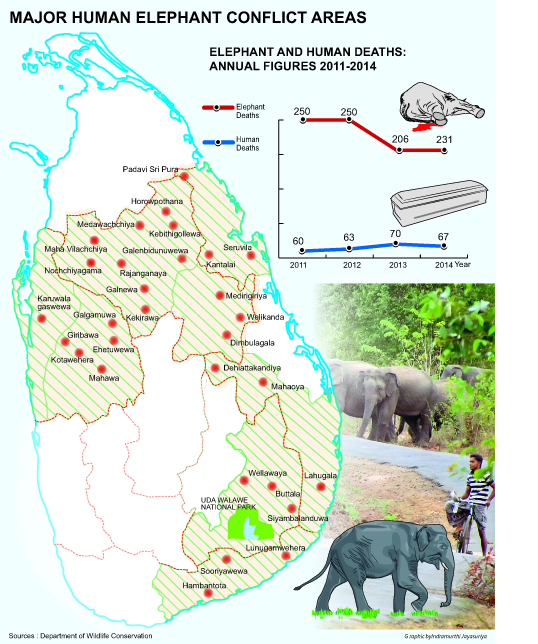

And why would Ashoka need all this information? To try to find information which will help in the mitigation of the HEC which is a lose-lose situation for both humans and elephants, he says.

His research covered many ‘border’ villages of the Uda Walawe NP including Pokunutenna, Laginagala, Neraluwa, Aluthwewa, Kilinbunna, Danwel-odaya, Dahaiyagala and Millagala. He also studied elephant movement in the Dahaiyagala sanctuary and animal corridor on the northern border of the park. The Dahaiyagala corridor links the National Park with Bogahapattiya, a savannah or talawa.

Ashoka’s modus operandi was to visit by day all these paddy and banana-growing villages to study crop-damage by elephants and await the arrival of the elephants in the villages at night.

While getting detailed answers from villagers to understand the human dimension of the HEC, Ashoka’s sojourns found permanent elephant footpaths in the gardens of the villagers.

“There was much hostility from the villagers initially,” he concedes because they are also the victims in the perennial HEC, as much as the elephants.

If the ‘pel-rakina’ menfolk in tree-huts nodded off for as little as 15 minutes on a long night, the elephants would lay bare the fields which they had toiled over, Ashoka was told, with much rancour against the DWC which they accused of not protecting their lives, lands and crops. They were also wary of him and it took a long time including discussions at the Dahaiyagala temple, house-to-house visits and trips in the jeep for youth to watch elephants, before they were convinced that the HEC was a complex matter and data collection was of paramount importance.

Ashoka does understand the plight of the villagers and empathises with them as much as he realises the need to conserve the elephants. “Imagine not being able to leave your home and your fields for a single day, be it to attend a function or a funeral. The men have to protect the crops and the women and children their homes and harvests,” he says.

The housewives came around first and then gradually the menfolk before the villagers could be persuaded to be part of the research effort which would lead to conservation. Thirty villagers have now been trained to collect data on the HEC.

He has proof of the villagers’ plight. “The footprints were very prominent,” says Ashoka, adding that the elephants “were coming and going” as they pleased particularly between 6 and 8 at night. He has also seen how nine bull elephants walked along the main road leading to Pokunutenne while four of the elephants’ favourite haunts have been caught on strategically-placed night-vision cameras.

As many as 25 bulls — sub-adults or those between 10-20 years old but not tuskers — would come to the villages in small groups or alone. About five of them were seasonal visitors to the park.

The lure for these bull elephants which would be scattered in forest patches at the edge of the park during the day and venture out into the villages at night was more nourishing and delicious food outside the park.

While the United Kingdom-based Rufford Foundation’s small grant has gone a long way to conduct this crucial research, many are the people who have supported Ashoka including the DWC’s Assistant Director of the Southern Range, Prasantha Wimaladasa, Uda Walawe Park Warden, Kelum Pathirana, Ranger Nimal Kaluarachchi and Veterinary Surgeon Dr. Vijith Perera; Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando and Dr. Jennifer Pastorini of the Centre for Conservation and Research; and environmentalists Ajith Sandanayake and Subash Tharanga.

The next project, meanwhile, for Ashoka is checking out the effectivity of the electric fence around the park, collaring the elephants to find out habitat use and get stronger evidence whether bull-groups frequently become crop-raiders and more awareness campaigns among villagers.

| Conclusions drawn from the research Here are some of the facts that have come to the fore from Ashoka’s |