News

Pakistani asylum seekers continue in limbo while living on the edge

An influx of Pakistani asylum seekers in Sri Lanka is putting a strain on the authorities dealing with the issue, as religious organisations supporting them are strapped for finances.

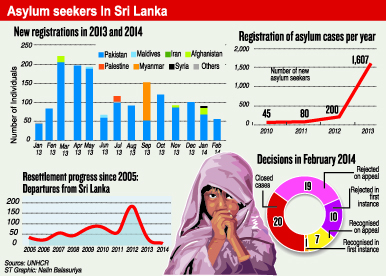

At least 100 more Pakistani asylum seekers arrived in the first two months of this year, after a sudden increase of arrivals since mid 2013.

According to statistics from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in Colombo, in 2013 alone they registered 1,489 asylum seekers, against 102 arrivals in the previous year.

Thus, UNHCR Country Representative M.G. Abbas told the Sunday Times that the organissation was not prepared to handle such a large caseload.

“Our focus was not on asylum seekers. Further, it is important for us to do the refugee status determination in a credible fashion. So we need to get the information and crosscheck the information, we need to review it to add our comments. The crosschecking takes time” he said, explaining the process followed in granting refugee status to Pakistani asylum seekers.

The asylum seekers are Pakistani nationals belonging to Christian and Ahamadi Muslim religious minorities who are seeking asylum on grounds of religious victimisation. They are not given any assistance until their application is processed, which may take up to two years.

“People already here, call their friends and family there. They get the information before they come,” says Moulavi K.M. Muneer Ahmad, of Ahamadiyya Muslim Jama’at mosque in Negombo, where most of the asylum seekers have sought refuge.

A majority of the asylum seekers arrive in the country on tourist visas, before filing applications as asylum seekers at the UNHCRcountry office. With no assistance provided by the UNHCR, the individuals have to fend for themselves or depend on donors.

As visa conditions stipulate that no asylum seeker can engage in economic activity in their host country, a majority of both the Christian and Ahamadi community, concentrated in the Negombo area, are dependent either on assistance given by the church, or on money sent by their relatives.

Those dealing with the refugee community are highlighting both economic and health related issues surfacing in some individuals.

“They are idling in a general sense of hopelessness for them. The futures of the children are in jeopardy,” says Fr Terance Bodiya Baduge, Parish Priest of St. Sebastian’s Church.

The community has a very close relationship with Fr Terance. He has been instrumental in organising the service and looking after the welfare of the Pakistani asylum seeker community. Most of them contact Father Terance whenever they need any assistance. Among them the most common is job placement which is always turned down.

However, the Sunday Times learns that some do work illicitly as shop hands, waiters and in other labour intensive jobs, leaving room for exploitation by employers.

“Most of them get paid only about one third of what is paid to a Sri Lankan. But as they have no choice, they still work,” said a member of the community who did not want to be identified.

Charles* the oldest of four children, was forced to flee the country due to their Christian beliefs. His entire family now lives in a single room in a building rented out by a small community of Christian Pakistani asylum seekers.

Narrating his tale through his teacher from the volunteer teaching centre, he says they would have been killed if they didn’t leave.“Once they tried kidnapping us when we were on our way to school. Luckily the driver of the three-wheeler saved us. So we wanted to get away,” he claims.

Another time his father who is a Pentecostal Bishop was abducted from the church.

“He was kept it jail for over seven hours. They beat him as well,” Charles explains.

His brothers and sister have accompanied their mother to visit their father who has been admitted to hospital suffering from a serious case of dengue.

Living cramped in a single room, with minimum facilities, is not easy. Over 34 people live in the same building as Charles, which has only nine bedrooms. There are three families with small children living in the facility. Similar to this facility are three others in Negombo rented out by Pakistani asylum seekers.

The rent is paid with the financial assistance from an organisation based in Europe called Pakistan Europe Christian Association (PECA). About 30 to 35 asylum seekers live in each building. The agreement with PECA will lapse in May. The community will have to either pay their bills on their own, or look for fresh sources of funding.

They are hoping the church will step in, if PECA does not fund them after May.

“But church funds are also scarce,” says Fr Terance.

Their only education: English lessons for young Pakistani women at the Ahamadiyya mosque in Negombo. Pic by Chathuri Dissanayake

“There are limits to what I can do. The parish is not a rich one”

Maintaining hygiene in overcrowded facilities with very limited resources is becoming increasingly challenging. Already four of their community has been diagnosed with dengue and two are in hospital.

Many others in the Christian community have rented houses on their own. They all congregate once in two weeks at the Holy Rosary Church, Kudapaduwa, Negombo.

The Ahamadi Muslim community living in Negombo is also plagued with health issues. Seven cases of malaria have been detected within the community, by Doctors from the Anti Malaria Campaign. The doctors, who received information on two malaria cases from Ragama government hospital, contacted Moulavi Ahmad regarding the issue.

Approaching the community through the mosque, the doctors were able to diagnose individuals suffering from malaria and treat them. Sri Lanka has not recorded any cases of indigenous malaria for over 18 months, and the authorities had to act fast to ensure the disease did not spread to the local community.

Accessing free services such as medical care is also rather difficult for both communities, due to the language barrier.

“The only thing free for us is medical services, but when we get there, they treat us as if we are not humans, especially the lower staff like security guards, ward boys and nurses. I don’t know why they treat us like that. Maybe because we are not Sri Lankan, or we don’t know their language,” said Eddy*, a Christian Pakistani asylum seeker who has been in Sri Lanka since July last year.

“The only thing free for us is medical services, but when we get there, they treat us as if we are not humans, especially the lower staff like security guards, ward boys and nurses. I don’t know why they treat us like that. Maybe because we are not Sri Lankan, or we don’t know their language,” said Eddy*, a Christian Pakistani asylum seeker who has been in Sri Lanka since July last year.

The children in both communities receive no formal education in Sri Lanka. To help remedy the situation, the church has organised an informal learning space in one of the churches. Four volunteers from the community have stepped in as teachers. They teach four main subjects including English and Mathematics.

“One of the biggest challenges is that we follow an international syllabi and it’s in the English medium” says Sheela*, a volunteer teacher at the centre.

The mosque has organised informal English classes for the asylum seekers’ children. In the absence of a formal education, many in the community are grateful for this opportunity. At present, about 65 children attend the class.

Rafiq Ahamad and 10 members of his extended family have been in Sri Lanka since December last year, living on savings. They decided to come to the country, because they heard it was a good option from asylum-seeking Ahamadi Pakistani’s already in Sri Lanka.

They value their freedom and the sense of security experienced in the host country, more than anything.

“We had to carry weapons everywhere. Anything can happen anywhere,” says Fizza Ahamad, Rafiq’s daughter.But underneath, other worries still persist. Ahamad who is living off his savings says that living expenses in Sri Lanka are mounting.

“I had a thriving family business. I have lost all now. My children went to the best schools there. Here they idle all day. We have no way of earning a living,” he says.

Fizza was studying a pre-med course in College in Pakistan. The studies have come to a standstill. Her siblings’ education has also stopped.

Currently, there are about 1,000 Pakistani Ahamadi Muslims living in Negombo area as asylum seekers, says Moulavi Ahmad.

Rafiq’s family has filed their application for refugee status last December, and still awaits a reply.

“Some have waited over a year for the process to finish, but got no reply,” says Moulavi Ahmad.

Many within the Christian community have not received a response from the UNHCR either. With no prospects for the future, many are idling.

“They should speed the process, recognise the genuine cases. There is a possibility that the situation may become like Sri Lanka’s irregular migration to Australia,” says Fr Terence.

Moulavi Ahmad agrees, adding that the mosque is not able to sustain for long the assistance given.

When contacted the Pakistan High Commission stated that most of the ‘asylum seekers are economic migrants who tend to misuse the visa regimes and travel facilities offered by other countries’.

“In order to achieve their objectives some economic migrants portray a negative image of their native country by fabricating various stories to strengthen their asylum cases with UNHCR,” a statement issued by the spokesperson of the Pakistan High Commission said.

However the mission expressed its confidence in the UNHCR on the organisation’s ability to verify claims made by asylum seekers.

“On receipt of information from the Sri Lankan authorities, the Pakistan High Commission extends all the necessary support. This Mission assists asylum seekers whose claims are rejected by providing visa and passport facilities as well as provision of return air tickets to the destitute Pakistanis,” the spokesperson wrote.

* Names have been changed to

protect identities

| Resource-strapped UNHCR unprepared to deal with Pakistani asylum seekers

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) was not prepared to handle the increased number of caseload, Country Representative M.G. Abbas claimed. “As of today, only 125 have been recongnised as refugees. Last year, the number of asylum seekers went up, with close to 1,500 applications being submitted,” he said. “It is also important to carry out the refugee status determination in a credible fashion,” says Mr Abbas as crosschecking the information received and conducting interviews takes time. “Further the need for interpreters also slowdown the process, and until and unless they are recognised as refugees, we do not provide assistance.” Appreciating the Sri Lankan Government’s move to give asylum space to those who are in need of protection, added that asylum seekers from nine nationalities have filed applications with the UNHCR to date. Mr Abbas also said that he has been working closely with government authorities to address the issue. However, he was not aware of the growing health issues among the Pakistani community living in Negombo, as they have no mechanism to monitor the asylum seekers once they file their applications with the UNHCR. “We have different organisations within the UN country team who can deal with any health situations, if local authorities have issues with accessing the communities,” he said. ‘Lack of resources is limiting the services that UNHCR is able to provide,’ Mr. Abbas said, adding that the organisation is exploring ways of obtaining assistance for the community through various channels. |