“It may without an exaggeration be said,” wrote James Longden, the governor of Ceylon, in 1880, “that there are no forests left of such value as to require or justify the creation of an expensive Forest Department.” Such had been the devastation of Sri Lanka’s forests under the British in their first century of ruling the island. Almost the entirety of the Central and Sabaragamuwa Provinces had been cleared for cultivating the crops that remain the mainstay of our economy: first cinchona, the plant from which the anti-malarial compound quinine is derived, and when that failed, coffee, tea and rubber.

|

Despite Longden’s skepticism, however, a Forest Department was eventually established in 1887, two years after the enactment of the Forest Ordinance, the main effect of which was to regulate the harvesting of timber from crown lands (all forests had in 1840 been vested in the crown through the Waste Lands Ordinance). It would be more than a century hence, in 1990, that Sri Lanka would prohibit logging in natural forests altogether, though even then only administratively, through a cabinet decision, rather than by a law that also binds the government. As a result, the government has retained for itself the right to clear forests when the exigencies of “development” so demand: hydroelectricity schemes, irrigation reservoirs, roads, village expansion and the like.

Today, the original 15,000 square-kilometre extent of Sri Lanka’s rain forests finds itself reduced to a number of tiny fragments that together add up to about 800 sq. km. That’s rather less than the area of Yala National Park. Sinharaja is just one of these fragments and, at 110 sq. km., substantially smaller than Yala Block I. By comparison with Yala it receives very few visitors, largely because being a dense rainforest, spotting charismatic animals like leopards in daytime is almost impossible. That, however, is not a bad thing. While Sinharaja offers little by way of recreation for the rubber-necked element of society, it offers a great deal to the serious naturalist. And of these there have been a good few. As for the rest of us, well, it is good to know it is still there.

But in the early 1970s it came within a whisker of not still being there. Anxious to provide the world with a continued source of cheap bathroom doors and pantry cupboards, the government had set up a Plywood Corporation with factories at Kosgama and Gintota, with the raw materials to be supplied from Sinharaja. This precipitated one of the most sustained campaigns of public protest, probably the first time an environmental cause had received such broad support in the country. Many conservationists of legend cut their teeth defending Sinharaja, whether by generating scientific information, advocacy, publicity or simply shouting very loudly. I was 15 at the time and only peripherally aware of the fuss, but the whole conservation alphabet from Abeywickrema to de Zylva came alive and, though the United Front government stood its ground, the project was finally abandoned following its ouster in 1977.

In 1978 Sinharaja became part of UNESCO’s network of international biosphere reserves. Then, in 1988 it became Sri Lanka’s first National Wilderness Heritage Area and was shortly thereafter listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I write “listed” advisedly, because that, unfortunately, is about all that happened. Nothing changed. The forest is surrounded by agricultural land and is subject to all the usual forms of attrition: illegal logging, hunting, plant collecting and the like, despite the best efforts of the Forest Department. It is, after all, an impossible boundary to defend: hundreds of kilometres, much of it without road access whether from inside or out. And even with the Forest Department having only recently absorbed a US$ 27 million loan from the ADB “to increase the value and sustainability of Sri Lanka’s forests”, little has happened save for fence posts (not amounting to an actual fence) being planted on the forest’s perimeter.

To its credit, however, the Forest Department has tried. It has given dozens of scientists access to the forest as a centre for research, resulting in some outstanding discoveries. Thanks to them, we now know a lot more about Sinharaja’s fauna and flora than the pioneer defenders of this site did in 1972. Some of this work, such as the experimental forest plot lovingly maintained and monitored by Professors Emeritus Nimal and Savitri Gunatilleke for the past 33 years, have produced outstanding science of internationally-recognized quality. So has the work of Professor Sarath Kotagama and his students in the field of bird ecology and behaviour. Sadly, neither of these projects is geared to provide information to casual visitors (this would cost money, a commodity from which the concerned scientists are anxious to shy away at any cost). Then again are the interesting ecologial studies on amphibians and small mammals by Professor Mayuri Wijesinghe and the discoveries of new species of frogs and mammals by Drs Madhava and Suyama Meegaskumbura. A lot is has happened and is happening; still more is urgently needed.

|

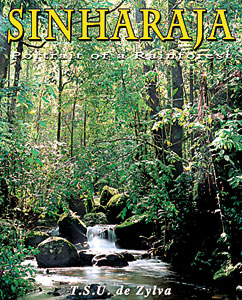

For the casual visitor, however, there is little to see. Granted, ever more twitchers (bird-watchers who travel to the ends of the earth to glimpse a rare spares) flock to Sinharaja to mark off one or more of its special and spectacular endemics, such as the Blue Magpie, Spurfowl or Green-billed Coucal. But the vast majority of folks who visit this site come away having achieved little other than to sample the atmosphere, or have had their own blood sampled by the abundant leeches. And it is to this constituency that Dr T. S. U de Zylva addresses his Sinharaja: Portrait of a Rainforest.

When T. S. U de Zylva’s Birds of Sri Lanka: a selection of fifty-six colour pictures was published in 1984, so wonderful was its quality that it became an immediate classic. It showed in the sharpest colour the kinds of intimate bird images previously seen only in Henry & Wait’s 1927 Coloured plates of the birds of Ceylon. For Dr de Zylva is a purist. He uses mainly Hasselblad cameras with 120 mm film (Fuji Provia 100, of course, ideal for the verdant hues of a rainforest): no digital shutterbug he. And so spectacular have been his results over the years that he has written and wholly or partly illustrated several excellent books, including Sri Lanka Jungle Profiles (1988), Wings in the Wetlands: A Photographic Portfolio (1996), Images of birds: a random selection of the birds of Sri Lanka (2000), A photographic guide to birds of Sri Lanka (2001, 2008) and now Sinharaja. I possess them all and, recently myself having taken up bird photography in Sydney, can only marvel at the labour, inspiration and blind luck that has gone into each of the images in these books.

Sinharaja: Portrait of a Rainforest is a richly-illustrated naturalist’s miscellany of Sri Lanka’s most treasured rainforest. Dr Zylva is at home here, knowing this forest intimately since first joining (in his own, modest, self-effacing way) Thilo Hoffmann to lobby for its protection through the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society in the early 1970s. The photos are excellent, of course, and come from both the western (Kudawa) and Eastern (Thangamale-Morningside) ends of the forest, or so I conclude from photographs of waterfalls. They range from sweeping landscapes to close-ups of ants and termites; and no, birds don’t get pride of place in this de Zylva opus. In fact, I was pleasantly surprised not to find the mandatory image of a Red-faced Malkoha anywhere in the book.

De Zylva’s Sinharaja is a kind of ‘enthusiast’s guide’ to this incredible piece of Sri Lankan real estate. Accompanied by a personal and informative text (Latin names are used sparingly and only when no common names exist), the photos succeed in conveying the atmosphere of the forest: damp, green, shadowless, almost completely lacking in direct sunlight, bringing to the fore the author’s skill in low-light photography. The text and pictures follow an order of sorts, focusing alternately on sites (e.g. the fishes of Maguru Wala) and phenomena (e.g. “Where are the flowers?”). And the text is almost always informative, dripping with snippets you want to remember so you can show off to your friends on your next visit, like the names of the mosquitoes whose larvae inhabit the broth in the pitchers of pitcher plants.

Sinharaja contains 136 pages of pure bliss, with each page evoking the author’s affection for this unique forest. It has clearly been for him a labour of love, and it is clear he could want nothing more than the continued protection of this treasure for all time. You cannot open this book without wanting to go there.

We need to remember that much of Sinharaja (including almost all that is accessible by the public) has been “selectively logged”. It is far from being a pristine forest, though a small, near-primary forest area does persist towards the middle. The result of this disturbance, despite it having been four decades ago, is that increasing numbers of alien species have become established in the forest, potentially a grave threat. No amount of protection will make these go away.

The need of the hour is for sustained, science-based conservation-management interventions that will ensure that the evolutionary processes that have gone on for millennia continue uninterrupted. This calls for an immense amount of scientific research, not just through weekend visits, but through decades of meticulous observation as done by the projects of the Professors Gunatilleke and Kotagama. Also urgently needed is renewed zeal from the Forest Department to invest more in conserving this forest. Dr de Zylva’s plea, “My beloved countrymen, please keep it this way” while apposite, may not be enough. We need to make it better. |