No permanent rivals in geopolitics

View(s):It equally applies to geopolitics as well: “There are no permanent enemies in geopolitics either”. The point I wanted to get across is that Sri Lanka, being a small country that is strategically located in the Indian Ocean, cannot afford to be a party to geopolitical rivalries in the region.

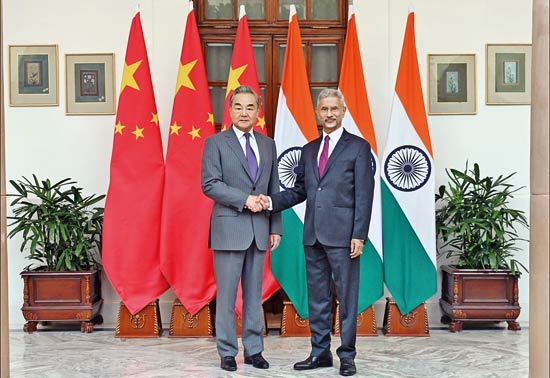

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar in New Delhi. Courtesy - news.cgtn.com

Instead, Sri Lanka must continue to play economic diplomacy, not political diplomacy. In fact, Sri Lanka has played it fairly well. Up and until now it remained a friend of all and an enemy of none although there were times that the country became a victim of geopolitical rivalries.

New chapter

For today’s column, I remembered the above comment due to an interesting incident last week that was caught up by international media: In a significant diplomatic overture, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar in New Delhi on August 18, 2025, marking a renewed push to stabilise and recalibrate Sino-Indian relations.

The high-level engagement comes amid a thaw in bilateral ties following years of tension, particularly after the deadly border clashes in Ladakh in 2020. India and China have had a tense relationship for decades—not just since the 2020 border clash in Ladakh.

Their rivalry goes back to the 1962 war and has continued with regular military standoffs and deep mistrust. They’ve often competed for influence in South Asia and beyond, whether through trade, infrastructure, or diplomacy. So, when their foreign ministers met about two weeks ago, it wasn’t just about solving recent problems—it was part of a much bigger effort to manage a long-standing and complex rivalry in the region.

Perhaps, it was not a coincidence as some observers believe India’s more pragmatic engagement with China came in the wake of President Donald Trump’s antagonistic treatment of India—through tariffs and public criticism. The meeting could be seen as part of India’s effort to diversify its strategic options and signal that it won’t be boxed into a one-sided alliance.

Perhaps, it was not a coincidence as some observers believe India’s more pragmatic engagement with China came in the wake of President Donald Trump’s antagonistic treatment of India—through tariffs and public criticism. The meeting could be seen as part of India’s effort to diversify its strategic options and signal that it won’t be boxed into a one-sided alliance.

It is quite unlikely that the US would be silent after this. Ironically, a new chapter of power rivalry might begin now.

“Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai”

They are the two largest emerging world powers with almost one-third of the global populations with fast-growing middle class. Both ministers emphasised the importance of strategic clarity, mutual respect, and peaceful coexistence, underscoring their commitment to transforming differences into dialogue rather than disputes. The meeting was framed by the broader geopolitical context, including shifting global alliances and economic uncertainties.

Wang Yi reiterated China’s readiness to expand cooperation and eliminate disruptions, calling for both nations to act as responsible powers in shaping a multipolar world order.

Jaishankar, in turn, stressed the need for a fair and balanced approach to multilateralism and emphasised India’s priority of maintaining peace and stability along the Himalayan frontier.

This dialogue coincides with the 75th anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two Asian giants, offering a symbolic moment to reflect on past challenges and future possibilities. India was one of the first few countries to recognise the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1950 although their “brotherhood” bondage was broken with border disputes in the 1960s.

Since the 1980s, there was a period of gradual normalisation through agreements on peace and confidence-building, while trade and cultural ties expanded. In the 2000s both countries were growing to be the regional and global power houses. Economic interdependence grew, and bilateral trade expanded, but strategic tensions simmered—especially around China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2013.

The two ministers acknowledged the guidance provided by the recent Modi-Xi meeting in Kazan, which laid the groundwork for restoring trust and institutional mechanisms. While no breakthrough was announced on the boundary issue, the tone of the meeting suggested a shared willingness to pursue de-escalation and long-term resolution through sustained engagement. As Wang Yi noted, the revitalisation of China and India should be complementary—not competitive—setting a precedent for regional stability and global cooperation.

Triangular geopolitics

Another influential big partner during Cold War era was the USSR – Union of Soviet Socialist Republics – that existed from 1922 to 1991, comprising many of today’s Central Asian and Eastern European countries including Russia and Ukraine. The USSR was one of the two superpowers during the Cold War, rivaling the United States in global influence, ideology, and military strength.

Although India followed democratic socialist and non-aligned political ideology, both Russia and China had command economies with centralised planning which was also adopted by India. The USSR played an influential role in economic and political spheres in post-Independent India as well as Sri Lanka.

It was in this geopolitical backdrop that Sri Lanka made its attempt to be a founding member of the ASEAN – Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 1967. On Malaysia’s invitation, the centre-right political leader and the then Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, Dudley Senanayake prepared to secure a seat at the ASEAN founding table in Bangkok.

Despite verbal confirmation from Thai officials who waited for Sri Lanka’s presence, it did not turn up for the Bangkok Declaration which gave birth to ASEAN. And Sri Lanka never got that opportunity again, as ASEAN too confined its membership only to Southeast Asian nations.

RCEP and BRICS

Later it was revealed that the geopolitical pressure and the internal opposition leaning towards non-aligned movement were influential and instrumental in closing that opportunity. But today, both India and China have entered FTAs with ASEAN, while Russia remains a strategic partner of ASEAN.

The group of six countries that have FTAs with ASEAN is known as “ASEAN + 1FTA”, meaning the ASEAN plus the six countries with individual FTAs with it – China, India, Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand. The most recent development is their Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership – the so-called RCEP. Although India was also a partner in these negotiations to set up RCEP, at the last stage it opted out.

Apart from that, all three superpowers are members of the BRICS group of countries as well – this group includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. BRICS has been working to reduce its dependence on the US dollar, which raised concerns in Washington—especially during the Trump era, when such efforts were seen as a challenge to US financial power. Although BRICS is not openly anti-US, its push for a more balanced global system including de-dollarisation intent carries strategic weight.

While China–India geopolitical tensions have historically posed challenges to cooperation within both RCEP and BRICS—particularly in areas like trade integration and leadership dynamics—recent diplomatic engagements suggest a cautious thaw. This has enabled incremental progress in BRICS coordination and reopened discussions around regional trade frameworks, even if full strategic alignment remains elusive.

Open economy of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s decision to liberalise its economy in 1977 marked a bold, unilateral shift in policy—undertaken without waiting for regional consensus. At the time, the geopolitical climate in South Asia was unreceptive to such openness, particularly given India’s strategic sensitivities. Sri Lanka’s pivot toward US and Western development assistance placed it at odds with prevailing regional dynamics.

Domestically, the country soon found itself engulfed in twin conflicts—an armed separatist struggle in the North and the JVP-led insurrection in the South. India’s involvement in both the trade liberalisation aftermath and the Northern conflict, including its role in the peace process, left a complex and often detrimental imprint. Sri Lanka continues to bear the scars of navigating this uneasy balance between internal reform and external influence.

In the decades that followed,Sri Lanka’s economic and political trajectory has frequently been influenced by the strategic leverage of external powers—particularly India and China. Perhaps, that time is over now; recent shifts in Indian Ocean geopolitics, which increasingly see India and China engaging in parallel rather than adversarial terms, may offer a rare opportunity. If harnessed wisely, this evolving dynamic could be a gamechanger—not only for regional stability but for Sri Lanka’s own development path.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor at the University of Colombo and Executive Director of the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) and can be reached at

sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk and follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).

Hitad.lk has you covered with quality used or brand new cars for sale that are budget friendly yet reliable! Now is the time to sell your old ride for something more attractive to today's modern automotive market demands. Browse through our selection of affordable options now on Hitad.lk before deciding on what will work best for you!