News

Elders’ homes: A devolved subject makes monitoring difficult

The absence of a monitoring and regulation mechanism for elders’ homes has led to profiteering by unscrupulous groups preying on the misfortunes of one of society’s most vulnerable groups, a Sunday Times investigation found.

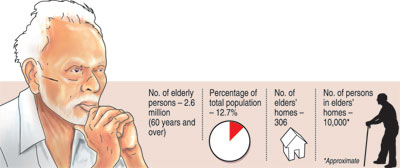

Over 2.5 million Sri Lankans are now over 60-years-old, according to the 2012 Census of Population and Housing—a massive 12.4 percent of the population. It is expected to rise to 27.6 percent by the year 2050.

Records reveal that there are 306 elders’ homes in the country, says the Ministry of Social Empowerment and Welfare. These include State-run homes and private ones. The latter is subdivided into two categories: non-profit care homes and fee-levying ones. The Ministry estimates there to be around 10,000 elders living in these homes.

But the actual number of elders’ homes—and the number of aged in them—is much higher, the Government concedes. Loopholes in the law are blocking authorities from keeping track of them all.

The Protection of the Rights of Elders Act of 2000 was the first comprehensive legislation to promote and protect the rights of the elderly. A National Secretariat for Elders and a 15-member National Elders’ Council (NEC) was set up to formulate policies for the treatment of the elderly. It is chaired by Secretary to the Ministry of Social Empowerment and Welfare. But social services is a devolved subject under the 13th Amendment. So the task of implementing national policy on elderly welfare is the responsibility of the Department of Social Services in each province. To further complicate this, the different Provincial Councils have given varying powers to their Departments.

The Western Province has some of the worst issues. Ten years ago, a Charter was drawn up for its Department of Social Services. At the time, there was no great problem of elders’ homes operating as businesses, said B. H. C. Shiromali, Director of the Western Province’s Department of Social Services.

So, the Charter only required private, non-profit elders’ homes to be registered with the Department. It did not cite penalties for non-compliance. The power to shut down unsuitable homes is not vested with the Department. It lies with the Provincial Council Minister in charge of social services. It can be a lengthy and time-consuming process, Mrs. Shiromali accepts.

The Government has set aside limited sources for elders’ homes. In the entire country, there are only four, fully State-run institutions: at Kaithady in Jaffna, Saliyapura in Anuradhapura, in Kataragama and in Mirigama.

Managed by the Western Province Social Services Department, the Mirigama home can house 240. Only those without living relatives or guardians, and bedridden elders, are admitted. No other home in the Province accepts bedridden aged.

In 2014, after repeated complaints about private elders’ homes in the Western Province, the Department did a survey which found 159 such homes. Seventy-eight of them were unregistered. There are still others that the Department has not identified, Mrs. Shiromali said. The vast majority of unregistered homes were found to be the ones that levied fees.

‘Mobile elders’ homes’ are another challenge. They are set up in rented premises, are strictly business-oriented, and lack even basic facilities. The main problem is that they have no set location. The managements move operations very quickly, making it difficult to track them down. A few days after official inspections, the homes shift elsewhere.

Not all unregistered homes are in poor condition. The authorities have found some non-profit and fee-levying institutions providing excellent service, and taking good care of their residents. But there were others with terrible conditions that made it impossible for anyone, let alone the aged, to live in them.

At one fee-levying home in Wattala for example, officials found more than 20 men and women living in a house with worms emerging from under the tiled floor. It was found that a poultry farm had been sited here earlier.

But the home was not closed down. It is still in operation, as are many others that the authorities found to be substandard. There were several reasons for this. The Department had no power to shut them down, Mrs. Shiromali said. And neither the residents nor their guardians wanted it to happen. The guardians were afraid they would be constrained to take back the residents; the residents feared they would have to move somewhere worse.

Homes also have no standard fee-levying structure. Differing amounts were charged for the same types of rooms and services. This lack of transparency meant many were being duped into paying more for basic facilities and care.

While one or two of the worst homes were subsequently ordered closed down, this was not a solution to the problem. “It didn’t take long for us to realise we can’t settle this issue using existing laws and through force,” Mrs. Shiromali elaborated. As such, authorities offered advice and assistance to the operators of these homes on improving their standards.

The response so far has largely been positive, according to her. Most of those who operated the homes, even the fee-levying ones, were doing a service to the community but were unaware about the finer points of setting up an elders’ home.

The Sunday Times visited several elders’ homes in the Western Province as part of its investigation. We visited both registered and non-registered homes. The homes covered included non-profit homes and fee-levying ones. What we found was that there was no clear standard for the homes. Some seemed well maintained while others seemed to lack basic facilities. Even those that were well-maintained had issues that raised concerns.

The management at all the homes made it clear that they were not prepared to accept an elderly person who was not capable of taking care of themselves. The reason given was lack of space for such persons, together with the shortage of staff to look after them. “There’s not enough staff and elders here look after each other’s needs. It’ll be difficult for us to care for someone if they are not even capable of walking unassisted,” one of those in charge of a care home we visited in Wattala said.

At one elders’ home in Kelaniya, which is run by the authorities of a temple, there were some 40 residents, both male and female, living in separate halls. The female section, which is visible as soon as one enters the premises, had 10 persons living in one hall, which had an attached bathroom.

One female resident turned verbally abusive when we inquired if there was a place to fill our water bottle. Another resident quickly came and ushered her aside, before apologising and explaining that the woman “is like that to everyone,” hinting that she was suffering from some form of psychiatric illness.

There was no proper fee levying structure either, just as officials found. Shared rooms ranged from Rs.8,000 upwards, while single rooms went up to about Rs.15, 000. At one so-called ‘exclusive’ home run by the authorities of a church in Hendala we were told selection was based on a face-to-face interview. A non-refundable deposit of Rs.50,000 was also required.

In July, last year, the Sri Lanka Standards Institute (SLSI) issued an SLS certification prescribing the requirements for elderly care homes for resident elders. Accordingly, elders’ homes that meet the required standards are awarded SLS Certification 1506. The standards needed to obtain the SLS certification however, are extremely rigorous. The certification’s scope covers everything, from emergency response and psychosocial care, to the positioning of windows and washbasins inside the care home. At present, it is not mandatory for an elders’ home to obtain this certification.

The Protection of the Rights of Elders (Amendment) Act No. 5 of 2011 made it mandatory for any institution providing residential care for elders to register with the National Elders Council if the institution has more than five residents.

As such, by law, the elders’ homes should register. Officials at the National Secretariat for Elders stated while they had been registering elders’ homes, the process had been halted temporarily until they were able to introduce more amendments such as making the SLS certification mandatory for elders’ homes. “It is unfair for us to insist on the SLS certification instantly. We want to educate those running elders’ homes regarding what is expected of them and give them a period to adjust,” a senior official at the secretariat, who declined to be named, told the Sunday Times.

Meanwhile, regulating elders’ homes is expected to be furthered streamlined by next year, once the SLS standard is made mandatory.

For those already in elders’ homes, the focus is not on keeping them confined there. They should be given the opportunity to take part in religious programs, go on trips and encouraged to work on learning new skills, such as making handicrafts which can be sold to earn an income. No matter how good the care is, it still cannot compensate for the sense of loss they feel at the home. “Those living in an elders’ home will never truly be as happy as those living among their children and relatives. This is why our second focus is on encouraging people to take care of elders in their own homes,” Mrs. Shiromali pointed out.