Big strides in keeping little hearts alive

View(s):The Lady Ridgeway Hospital’s Paediatric Cardiothoracic Unit reaches the milestone of 1,307 surgeries of which 1,070

were ‘major’ in 2014. Kumudini Hettiarachchi reports

Adjacent rooms with muted instrumental music playing in the background cutting out the hustle and bustle of the cries of children and the sound of worried parents rushing about.

Purposeful are the teams scrubbed up and green garbed in the two rooms, for in their hands they are holding two tiny hearts.

Dedication and skill: The team headed by Dr. Munasinghe. Pix by Indika Handuwala

The hearts, one of a year-old baby and the other of a 10-day-old newborn, are undergoing major surgery in the Cardiothoracic Operating Theatres of the Lady Ridgeway Hospital (LRH) for Children, Colombo, under the skill and expertise of the teams headed by Consultant Cardiothoracic Surgeons, Dr. Mahendra Munasinghe and Dr. Kanchana Singappuli, respectively.

We see these heart operations on February 2 and the Paediatric Cardiothoracic Unit is pulsating with joy, for it has notched up a record 1,307 surgeries last year (2014) of which 1,070 were ‘major’ ones.

As the little hearts are made to stop beating, stilled and emptied to enable the surgical teams — ably supported by the anaesthetist, perfusionist and nursing teams — to perform complex surgery, the heart-lung machines (ventilators) take over the vital task of keeping the babies alive.

In wonderment, the Sunday Times team too, masked and gowned, looks on as Dr. Munasinghe’s ‘blue baby’ from Katugastota has three of the four major defects in a condition called Tetralogy of Fallot are corrected, with the fourth automatically righting itself.

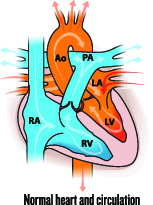

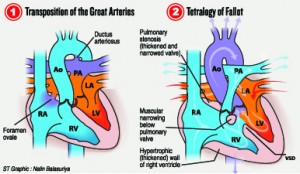

Dr. Singappuli, meanwhile, who is dealing with a tinier baby-heart is attending to a different complex defect – the Transposition of the Great Arteries. (See graphic)

The Paediatric Cardiothoracic Unit has reached a major milestone, explains Dr. Munasinghe when the Sunday Times meets him a week later, only to find that the one-year-old has already left with his parents for their humble home in Katugastota.

The unit’s heart surgeries are performed by Cardiothoracic Surgeons Dr. Munasinghe, Dr. Singappuli, Dr. Y.K.M. Lahie and Dr. P. Ratnayake.  Working in tandem with them are: Consultant Anaesthetists Dr. A. Perera, Dr. D. Jayawickrama and Dr. M.M. Premaratne along with Consultant Cardiologists Dr. Duminda Samarasinghe, Dr. S. Perera and Dr. R. Morawakkorala and junior doctors and Operating Theatre, Intensive Care Unit and ward nurses.

Working in tandem with them are: Consultant Anaesthetists Dr. A. Perera, Dr. D. Jayawickrama and Dr. M.M. Premaratne along with Consultant Cardiologists Dr. Duminda Samarasinghe, Dr. S. Perera and Dr. R. Morawakkorala and junior doctors and Operating Theatre, Intensive Care Unit and ward nurses.

This unit opened in 2007 has been dealing with the heart problems of children and it was in 2014 that we jumped the 1,000-mark, points out Dr. Munasinghe, justifiably proud of this achievement.

Located on the ground floor of the LRH, in the Cardiothoracic Operating Theatres four to eight surgeries are performed every day. This unit has carried out the largest number of heart operations by a single unit in a year, he says.

It is linked to the Paediatric Cardiac Unit of the University of Arizona, Phoenix, America and the University of Southampton, United Kingdom, which in comparison carry out only about 300-350 surgeries per year, it is learnt.

Each year, according to him, 2,500 children are born with congenital heart disease of which 1,400 require surgery. Jogging the memory of Sri Lankans, he recalls how before the unit was opened numerous were the photographs of pathetic children in the newspapers, with parents seeking help from the public for heart operations. But not any more.

Before 2007, a few paediatric cardiac surgeries had been performed at the National Hospital, Colombo, and the Karapitiya Teaching Hospital, Galle, in the state sector and some private hospitals in Colombo. A few parents who could collect the money would take their children abroad.

“Unfortunately, 99% of the parents just could not find the money, amounting to anything between Rs. 600,000 and several million rupees. So the children were very sick and would be in and out of hospital. Many also died,” says Dr. Munasinghe with emotion.

Slowly but surely, the Paediatric Cardiothoracic Unit has been built up, performing surgeries free of charge. Many are those who have helped the

Heart stopping moment: Surgery being performed on a one-year-old

unit along the way, individuals as well as companies and multinationals sending their ‘mite’ in the form of a few hundred to millions of rupees, he says.

“The Health Ministry has always responded whenever there was a need, but when there has been a sudden shortage of consumables, a donor has been found and the LRH has never-ever had to ask the parents of the sick children for a cent,” he says, adding that items such as soap, pampers and even bus-fare have also been provided to these families due to the generosity of donors.

He points out that sometimes people are quick to find fault and highlight a few shortcomings but the value of the free health system which provides preventive and curative care is hardly acknowledged. “Sri Lanka is probably one of the few countries in the world where heart surgery is performed free of charge.”

| Complex operations Premature babies weighing as little as 600gms or teenagers up to 16 years old, as well as emergency cases rushed straight from the ambulance to the operating table, newborns on the verge of death or those with congenital heart disease. All these victims of heart troubles from the remotest corners of Sri Lanka undergo life-saving surgery at the LRH Paediatric Cardiothoracic Unit. In the congenital heart disease of Tetralogy of Fallot in the blue baby we saw that day, earlier there would have been only palliative care available in Sri Lanka. The four defects he had were – a large hole between the two lower chambers of the heart; the aorta partly arising from the right ventricle (usually should be left ventricle); the right ventricular outflow valve being obstructed by abnormal heart muscle growth; and a thickened right ventricle. “It was a complex intra-cardiac repair,” says Dr. Munasinghe, adding that when you tackle the first three issues, the fourth gets corrected automatically. A mass of scissors seem to be in the tiny chest, as the team systematically, slowly, slowly stops the heart and bathes it in cold saline to cool this vital organ to reduce the oxygen demand by the heart muscle. The different-coloured lines on the beeping monitor indicate the status quo of the little one. The ECG is a straight green line, for heart activity has been halted, blood pressure is maintained with the red line rising and dropping in peaks and valleys, while the blue line shows oxygen saturation is 100%. Like a craftsman, Dr. Munasinghe shapes a white patch from an artificial material called gortex to create a new valve for the defective and narrowed one. After a while, we step into the adjoining OT and find Dr. Singappuli working on the 10-day, 2.2-kilo baby girl. Here it is an arterial switch which is happening, for instead of the aorta arising from the left ventricle of the heart and the main pulmonary artery from the right ventricle it has happened the other way round. So Dr. Singappuli will make the switch of the main arteries and re-implant two tiny coronary arteries to the new aorta. These are just two of the complex operations performed at the unit. The others include atrial septal defects; ventricular septal defects; atrioventricular canal defects, univentricular repairs; total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage; partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage; valve surgery; valve repair or replacement; truncus arteriosus and the list goes on. Where young surgeons are reluctant to tread A crisis is looming with regard to heart surgery in Sri Lanka, warns Dr. Mahendra Munasinghe, pointing out that young surgeons are reluctant to take up this speciality. To the question ‘Why?’ the answers seem obvious – to be a heart surgeon there is a need for longer training (at least seven-eight years), while it is difficult work with numerous risks, a demanding job and fewer rewards. Backing up his concerns with facts, he says that in 2005 there were only two cardiothoracic units at the National Hospital and Karapitiya and only three heart surgeons. Ten years on, there are four units – with the earlier two and the LRH and the Kandy Teaching Hospital – with only 13 heart surgeons. “We have lost quite a few heart surgeons who have understandably sought greener pastures abroad or in the private sector and will lose more when others retire.” With the Association of Cardiothoracic Surgeons signalling the red-flag of an impending crisis, the urgent need is to attract young surgeons to this field, he says, suggesting that the incentives to young heart surgeons should be based on training and skills, like any other specialized field. The country needs to look after them. Currently, a heart surgeon’s salary is less than that of a bank clerk. Act now or this field will be crisis-ridden in about five years, adds Dr. Munasinghe. |