|

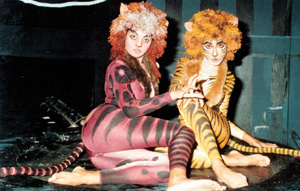

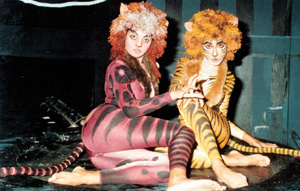

Memories: A scene from the

1994 Cats production |

The performance by the Workshop Players on the night of Sunday, March 4 was met with a spontaneous standing ovation as the curtains came down. Sitting down amidst something so euphoric, felt almost mean; and yet, I could not stand up for a performance that I honestly believed did not warrant an ovation. The theatre that night was certainly filled with enthusiastic prolonged applause, but what was significant about that moment really was the dimension of recognition.

What could have easily tipped that evening was the feeling that here was an exhibitionist, albeit endearing, family parading a rather self-indulgent ritual together. Instead, despite the ridiculous glitches in production, there was the sense of the carnivalesque –the practice of inverting order –and consequently, here were the children enjoying the licence to mimic, to inhabit the place of, the father. What was being recognised in the performance itself, and its response, was the contribution made by one man to a theatre culture of a society in terms of a body of work, a generation of players and a theatrical and cultural memory that is born of the experience of seeing a landscape of work in performance.

Read in that light, the lines, ‘memory, all alone in the moonlight, I can smile at the old days,’ from one of the opening acts were poetic dramaturgy. Noeline Honter singing Memory from the musical Cats was iconic – more so because that moment could not be simply received. There was a sense of a split self somehow; sitting in the present, but responding from a different place, a different time.

Remembering is rarely an act of simple recall. Elizabeth Jelin articulates it best in her text State Repressions and the Labors of Memory: She describes the processes of ‘memory’ as complex; a labour where the mind that is consistently subjective, identifies, digests and tries to make sense of both personal and collective experiences. Although located in a completely different context, it is possible to draw on her understanding of memory to express something of the sensation I experienced during some moments of the performance.

In these moments, I was a teenager again, burning with the desire to be on a stage, envious and hopeful seeing young people making it there. I was paralyzed by the liveness of the cats of 1994 (completely embodied, compared to the preening pretention of the ones of the present). The scene was playing, the song continued, but I was seeing the cats from the past, running off the stage in the interval, creeping up behind you and finally settling in the window ledges in the foyer of the Lionel Wendt. I saw Mr. Mistoffelees, and the Jellicle Cats and the Gumbie Cat who sits and sits and sits and sits.

And this, for me, was what was intriguing about the performance; its ability, and its project in some ways, to manipulate memory – sometime artistically (the playing of Fagin from Oliver by Manoj Singanayagam), but mostly through the emotion generated in performance(the ensemble playing of Lion King and Sanith and Surein de S. Wijeratne’s rendering of Pumbaa and Timon).

Ruwanthie de Chickera’s performance in Les Miserables was a highlight. It’s the first role I saw her in (ages before I knew her). Her moment on stage, amidst an ensemble, was for me when the nostalgia of remembering and the aesthetics of performance came together most successfully. She possesses a craft of character playing that is concrete and a style of performance that is joyous. And I saw that embodiment of character again that evening, in Serala Athulathmudali playing Christine. The sense of vulnerability that Serala’s Christine managed to hold onto in the small movement of her hands, despite the sheer power of her voice and presence, captured for me, in the larger scheme of things, the vulnerability of the creative work.

The excerpt from The Phantom of the Opera was interesting not just in terms of the playing of the scene. Here was a piece that we, as an audience, didn’t have a previous reference point for in performance; and thus, no theatrical memory. Where then do our memories come from? From a different landscape: Invested in the build up of publicity campaigns, and excited talk of fire-proofing the Lionel Wendt stage for pyrotechnics. And then of candles lit and stage-doors closed.

What this meant was that the musical theatre culture centred in Colombo, and spearheaded by Jerome de Silva, had not just entered, but had also scratched the surface of the world of contemporary playing – where economics, licence and ownership were setting the parameters for the act of performance. The realities of copyrighted work hit hard, and Phantom was closed down. And while the principles of intellectual property and artistic ownership are not to be contested, it is important to recognize that through the Workshop Players a specific world of performance opened for the audiences of the English stage in Sri Lanka in the 1990s. And this was the world that we glimpsed in this anniversary performance.

Jerome de Silva belongs to a time when directors of the English theatre in Sri Lanka were trying to push the limits of conceptualising and staging performance. However, in no way was the work culturally located, nor did it speak to the political realities of the time like the work of the Sinhala theatre of the 1990s. Ruwanthi de Chickera records this in her article ‘Aspects of the Theatre,’ where she notes,“Although these were definite attempts to throw back the curtains of English theatre, the improvisations tended to remain within certain “safe” zones” (www.frontlineonnet.com).Reviewers of the time like Regi Siriwardene demanded activism in the English theatre, writing against what was perceived as “a popular formula for escapism” that had begun to appeal to the English-language theatre audiences (www.frontlineonnet.com).That said, Jerome’s work explored, and celebrated, the theatrical style and spectacular staging of the Broadway show – and, though it can be argued his work was not particularly original, he consistently delivered within the aesthetic he had chosen.

Given this history, the evening was disappointing. Aspects of it just did not work, especially in the latter stages of the show, for different reasons: The absolute lack of creativity in imagining space and stage, the one-dimensional flatness of the badly-projected film (which, for the most part was unclear), the sometimes amateurish performances, and the heart sinking moments when the memory of the performance overshadowed the actual performance moment on stage. The playing of Evita as the closing act, and the projection of what is to come, served only to alienate; inadequate interpretation and unconvincing playing could not sustain the rush of feeling inspired by the opening acts. All this was forgivable in the face of the malfunctioning sound system.

Still, the magic of live performance lies in the sensorial; in that which is recognized, in an experience shared, and a moment in time collectively remembered. And, on evenings such as this, when that memory is invoked with an enthusiasm of spirit, that is what we stay for. It is important to note this, for this was a production advertised to a paying audience – and it is significant that a culture of spectatorship demands of its theatre makers and performers’ responsibility and reflection in their work. If not, despite the history, experience and memory recognized, and celebrated, this work remains amateur. A ‘professional theatre’ – is not easily defined. However, what was significant about the early Workshop years was that the ethos of a professional theatre was embedded in the work. Maybe this is what I remember; maybe this is what I missed. |