Coincidentally, considering the time of year, “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding”, a mystery story by the Queen of Intrigue, Agatha Christie, popped up as we were tidying the house for the season. Appropriate reading, we thought, for the December 25th weekend.

This brings to mind one especially bookish childhood Christmas, in the early ’60s, when we woke up to find at the foot of the Christmas Tree a bright splash of detective fiction: “The Body in the Library”, “The Murder at the Vicarage”, “Crooked House”, “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd” – it was an embarrassment of Christies.

It was the year Christie fever had taken hold – a condition that 10-to-13-year olds of a certain disposition are prone to; in our case it remained uncured for the next five or six Christmases, until we moved on to other literary thrills, of the more Advanced Level category.

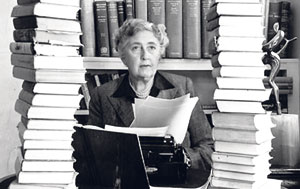

|

| Agatha Christie averaged a book a year during her most productive years. |

The result of that early reading affliction was that for the rest of one’s life the sight of an Agatha Christie could trigger a particular excitement – a frisson that associated mystery books with Christmas flavours and atmospherics. In fact, “a Christie for Christmas” has become a seasonal gift slogan in English-speaking societies the world over.

When we were very young we visited two aunts – great-aunts, in fact – who kept a home that lived Christmas 356 days a year. It was a home stocked with food of a highly Christmassy order, the larder and the refrigerator perennially filled with cakes, puddings, desserts and sweetmeats.

It was also a home filled with books. Sweet treats and books alike awaited all who called on Agnes Spittel, former headmistress of St. Paul’s Milagiriya Girls’ School, and Lottie Jansz, former teacher at Bishop’s College, Colombo.

The Christmas season itself was a time of elaborate preparations and generous proportions, when the sisters undertook the curing of a giant leg of pork to last the season; the distilling of litre upon litre of red-tinted lovi-lovi wine; the beating, mixing and baking of dozens of Breudhers, and the putting together of spice-laden, eggs-intensive Christmas Cake, Love Cake, and Jaggery Cake, all to be given away, and all made to Grandma Elinore Zilia Spittel’s 19th-century Dutch Burgher recipes.

These precious family recipes were eventually shared with lovers of good food when the sisters, as retired teachers, opened a cookery school, Cuisine Milagiriya, back in the Forties. The cookery classes were held at the Vicarage of St. Paul’s Milagiriya, where Lottie’s husband, Canon Paul Lucien Jansz, one-time Sub-warden of S. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia, was Vicar. The idea of the culinary school came from Canon Jansz, scholar, linguist and himself an appreciator of fine dining.

After the Vicar’s death, in 1953, the sisters moved to Police Park Terrace where they continued to hold their cookery classes. By the end of the ’50s, the sisters had decided they were through with teaching and closed the cookery school so they could live in undisturbed retirement. Visitors – family members, friends, fellow teachers, former students, parishioners and well-wishers – continued to call, and no one left without enjoying a typical Cuisine Milagiriya treat.

In their retirement, the silver-haired sisters – Agnes wore her hair short, while Lottie boasted a magnificent, almost ’20s-style “platinum blonde” head of naturally wavy and sheeny hair – would spend much of their time reading. There was always a book – in hand or at arm’s reach.

|

| The majority of Christies are set in the Twenties, Thirties and Forties. |

The books in the sisters’ home were tidily arranged, on shelves and inside glass-fronted almirahs. Scattered among the nut-brown Dickens, the black velveteen Thackeray, the gilded devotional books, and the small-print dictionaries and language primers were dozens of detective stories, all first-edition Crime Club hardcovers.

As a long-ago birthday gift to his wife, Canon Lucien Jansz had placed a standing order with his London book dealer to send Lottie twice a month the “best thriller” published each fortnight. These books arrived regularly, and Canon Lucien Jansz would inscribe them on the inside cover in his singular handwriting, in green or red or purple ink. The volumes opened to the words “Lottie’s seventeenth book, September, 193-”, “Lottie’s 37th book, February, 194-,” and so on. Lottie was a dedicated consumer of mystery fiction.

The fortnightly passage of mystery books from England to the Vicarage of St. Paul’s Milagiriya, Ceylon started in the ’30s, ran through the ’40s, and halted abruptly in 1953, with the sudden demise of Canon Lucien Jansz.

From her rattan lounge chair, as she read The Book of Common Prayer or the Daily News, Lottie would watch us through the corner of her thick spectacles. She did not approve of 11-year-olds losing themselves in mysteries. Ever the teacher, she believed firmly in schoolbooks and homework first, and light reading a far second, or to be avoided altogether. When we sought permission to borrow, she would say, her eyes hard and no-nonsense, “You may have the book, but class-work comes first. Remember that.”

We studiously went through all the detective books, but the two we most enjoyed were “A Murder Is Announced” and “The Sittaford Mystery”, both Agatha Christies. The first had an appetising apple green cover, the second an orange barley cover.

We wanted more, but that was all there was. The absence of more Christies was a mystery and called for an investigation.

If Lottie Jansz was receiving the “best” detective book of the fortnight, and if “Sittaford” was the first of Lottie’s fortnightly thrillers and “A Murder Is Announced” the last she received, we are left with two full decades of unaccounted for Christies. The reigning Queen of Crime’s books would surely have been on the London bookseller’s list. We did some calculating: “The Sittaford Mystery” came out in 1931 and “A Murder Is Announced” in 1950; the two decades between were some of Christie’s most productive years, when she wrote more than 30 novels. And yet Lottie Jansz had only two Christies in her collection. What had happened to the other 30 or so titles that she should have received?

There was only one solution to The Mystery of the Missing Christies: They were stolen! Borrowed, never to be returned, by the hundreds who called at the Vicarage during the’30s and ’40s.

By our late teens we had moved on to other things and would not pick up another Christie until many years later, when, rummaging through a second-hand bookshop in the Far East, we found a deliciously lurid-looking paperback (dark blood oozing out of occupied armchair pierced by ornamental dagger) of “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd”, the classic 1926 whodunit with the unguessable conclusion. “Ackroyd” employs a narrative trick that can be used only once in mystery fiction.

We took the book home and, reading for old time’s sake, settled into a story we recalled only patchily from 30 years back. The typical Christie elements were all there – the cosy English village setting, the likeable eccentrics, the arch, playful dialogue. One chapter made us laugh out aloud. A game of Mah Jong is in progress. The main characters are discussing the murder investigation as they play their hands, the conversation moving in a counterpoint of whimsy and gravity, dancing between play and foul play. (As we chuckled, through the window of our Happy Valley apartment came the clatter of a real Mah Jong game – that pervasive tiles-on-table rattle that is built into the background noise of any Chinese community.)

“The Murder of Roger Ackroyd” brought back blissed out teen years of steady book consumption. The detective story, as a genre, was a joy, and still was. “Roger Ackroyd” had it all – the easy-going early chapters, the suspenseful scene-setting ahead of the murder, the tensions of the investigation, and the change of tempo and temperature when, in the last swift pages of an otherwise sunny and breezy narrative, the atmosphere drops from cool to chilly to freezing as the killer is cornered.

And, of course, there were the entertaining digressions – Christie’s humour was part of the treat. (The writer, who was married to an archaeologist, remarked that “an archaeologist is the best kind of husband a woman can have – because the older she gets, the more interested he becomes in her.”)

And there was something else in that serendipitous reading experience – something sensed and finally understood, as we mused, Christie in hand, in that Chinese city far from home. The book had a familiar warmth – like a gift from long ago, a gift from a great-aunt long departed. What was it? Suddenly, we knew.

The world of an Agatha Christie English mystery is reflected in the world of the British Empire’s outposts. The ’20s, ’30s, 40s storybook Englishness extends into the colonial Ceylon of the early and mid-twentieth century. The English town and village life, the Anglican Church milieu, with the vicarage at the centre of things, the vicarage tea parties and the vicarage jumble sales, and the rest of it – all are present in the colonial inheritance. That explained our subliminal shock of recognition on reading a Christie.

And then we saw, clearly, yet another level to this familiarity. This time it was a familial familiarity.

The family albums go back two generations, showing aunts and uncles dressed in ’20s, 30s and ’40s styles. These were the years the Christies were coming out at the rate of at least one a year.

The Christie social set had women in flapper fashion, with dropped waistlines and bobbed hair, or in empire-waisted gowns and butterfly sleeves. They wore cloche hats, pillboxes, berets and brimmed hats. These were the same clothes and hats that great-aunts in Ceylon wore when they went to weddings and the races. In their heyday, Agnes and Lottie and sisters were fashion-savvy ladies.

And there was more to all of this familiarity.

As a vicar’s wife, Lottie for 35 years presided over vicarage tea parties, vicarage Christmas parties, vicarage luncheons and dinners; the foods served at these functions were the kind of foods people at a vicarage party in a Christie mystery would consume – raisin cakes, scones and cucumber sandwiches, Charlotte Russe, custard puddings, and semolina cakes.

When we first met our great-aunts, they were already elderly, though sharp-minded, widows and spinsters – not unlike (come to think of it) the silver-haired Mrs. Christie herself, and her famous lady detective, Miss Jane Marple.

This was a world of scholarly clergymen, elderly eccentrics, retired Army officers, home-visiting doctors with black bags, and retired persons visiting solicitors to draw up their last wills. The difference was that in the world of an Agatha Christie, an innocuous bottle of smelling salts, a phial of aspirin, a glass of wine, or a dish of plum pudding could turn sinister.

Agnes was born in February 1883, her sisters Lottie in March, 1887, Marian (the grandmother we never met) in July 1888, Bessie (Elizabeth) in May 1892, and Beatrice in October, 1896. Agatha Christie was born in December 1890. The Spittel siblings were compulsive readers, and Agatha Christie was a part of their reading universe.

When we open a Christie, the two worlds – a dated England and a colonial Ceylon of great-aunts and uncles – come together, overlapping and blending artistically .

In her introduction to “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding”, Agatha Christie writes that the book “recalls to me, very pleasurably, the Christmases of our youth. … What superb Christmases they were for a child to remember. … The Christmas fare was of gargantuan proportions. … Oyster Soup and Turbot … Roast Turkey, Boiled Turkey and an enormous Sirloin of Beef. … We then had Plum Pudding, Mince-pies, Trifle and every kind of dessert. … How lovely to be eleven years old. … What a day of delight. …” |