My Grandpa who ‘ran away to sea’

One day, around noon, two schoolboys were walking home from school. It must have been about 1883, and the boys were from S. Thomas’ College at Mutwal. Mutwal and Kotahena were, then, the home of upper-middle-class people, many of them Burghers.

On all these ships he sailed he was the only man from Ceylon and so he was called “Ceylon” by his shipmates on every one.

The two friends were Burgher boys and, like all their clan, they were adventurous and independent. School did not, probably, hold much attraction for them. They lived very close to the busy port of Colombo, though Galle was yet the country’s main port. With the coming of steamships the port of Galle was proving to be a risky haven. In fact, soon after this fateful day, Colombo was chosen as our main port and Galle became a peaceful back-water.

The two schoolboys ambling back home after school knew nothing of this, nor would they have cared. Ships, though, fascinated them, as they have fascinated boys throughout history. Ships of many countries; seamen of many colours speaking queer languages; majestic sailing ships, tall-funneled paddle-wheelers, some still carrying sails for an emergency; flags of many nations, the smell of coal and gritty black smoke, bullock carts trundling over cobblestone roads carrying cargo from the warehouses, nattamis pushing their hand-carts and loudly cursing all who crossed their way – all the hustle and bustle of a busy port open to the sea (there was no breakwater, then). So the two boys were probably exchanging tall tales about shipboard life on board exotic countries they sailed to.

By-and-by, they came up to the entrance to the port and hung around it, drinking in all the strange smells and sounds. Suddenly they saw, pasted on a window in an office, a large notice: “CABIN BOY WANTED”. One, the more adventurous of the two, made a quick decision and walked boldly in. Boldness was his friend: soon he was back with a beaming smile – he had got the job! Now came the ticklish question of telling the family, who were sure to sabotage the adventure. Flushed with success, he made another quick decision. He persuaded his friend to take his books home, two days later, and tell them that the vagabond “had run away to sea”. By the time this was done the ship and the new (and probably seasick) cabin boy had sailed away.

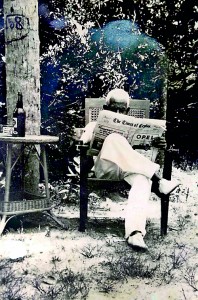

From the family album: Lloyd Oswald Felsianes enjoying his morning read

That boy was my mother’s father, Lloyd Oswald Felsianes, and his story gives me a link to the “Great War” that was meant to save Civilization a hundred years ago (but didn’t) but only began a race for domination which goes on today. It is the story of a peaceful man caught up in a war he had no interest in. So let me say something about my “Dehiwela Grandpa”.

My earliest memories are of him in his late seventies or early eighties, a wiry man of average height, about 5ft. 5 or so with close-cropped white hair, white moustache, and a large, pitted, pink nose. Always dressed in white singlet, white slacks and white deck shoes, he chewed sticky stumps of “baccy” (chewing tobacco). A very faded, sepia picture (since restored) shows him in his ‘thirties, on shore leave in Singapore. It shows him in a dark three-piece suit and he sports a watch-chain.

He had tattoos on his forearms, one of a mermaid – he assured us that he had seen them! He told us he had sailed the seven seas, on many ships and right round the world. What ship did he sign on? We don’t know but, somewhere along the line the cabin boy became involved with the Engine Room and became – as my Mother remembered – an “Engineer”.

And so, after sailing the seven seas, the prodigal returned home in the late 1890’s, married and settled down in Dehiwela with his family, working on the cargo-cum-passenger “Lady” ships (“Lady Blake”, “Lady McCallum” and “Lady Havelock”) which the Ceylon Steamship Co. Ltd. operated around the island. (I remember the High Priest of Seruwavila temple telling me “Api may ratata aawey naven – We came to this country by ship”: that “country” being Trincomalee!). One of them would leave Colombo on a voyage round the island on every other

The medals that were awarded to Lloyd Felsianes

Wednesday. She would sail round the southern coast, stopping at Galle, Hambantota, Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Point Pedro, Jaffna, and end up at Pamben. She would make the return trip to Colombo every other Friday. The round trip took eight days. The ships are no more: the “Lady Havelock” came to grief in Batticaloa in the cyclone of 1907 and her boiler, which Grandpa must have tended, was said to be yet at rest in a garden opposite the Rest House – at least, till the tsunami.

Somewhere during this period, he came to know a POW in somebody else’s war: the Boer War. We don’t know anything about this except for a gift the POW had given him. It was a pipe, for smoking, carved out of the root of a tea bush. Along the stem he had carved “Boer Camp, Diyatalawa” and, on the bowl, the coat-of-arms of the Orange Free State.

But the “Ceylon Steamship Company” wound up in about 1908 and he had to fend for his wife and three small girls. Having divorced and re-married by this time, a berth on a merchant vessel was no longer an option and so he joined the Colombo Port Commission as a Tug Driver. My Mother remembered two he worked on – “Samson” and “Goliath” – perhaps because of their Biblical names, but there may have been others, too. It was a quiet life in a port that was becoming increasingly busy. Ships were not berthed alongside the quays then, but were anchored in the stream, with bows facing the prevailing monsoon wind. When the monsoon changed, the berthed ships were swung round to face the wind again. So the Tugs were always tuned to wind and wave and it was a most routine job.

But all that changed, a hundred years ago this month, when the Great War caught up with him. Colombo was an important port for the British Empire, because of sea-borne trade and travel. The Indian Ocean became a happy hunting ground for German submarines, and raiders. The greatest fear was of the “Emden” which was cruising, preying on merchant shipping: ships were sunk, cargo taken over and also the ships’ crews and passengers who were treated humanely and sent home by various ships that were spared from a watery grave to serve this humanitarian purpose. But, although she entered the popular Sinhalese vocabulary, the “Emden” never did sight Ceylon, though sailing past her. Not so another raider, the “Wolf” which was a raider and mine-layer. The “Wolf” laid mines in the Approaches to Colombo Port which, accounted for the British freighters “Worcestershire” (7175 tons) and “Perseus” (6728 tons) even as late as 1917. Clearly, Colombo had to secure the Approaches by sweeping and clearing mines laid.

But all that changed, a hundred years ago this month, when the Great War caught up with him. Colombo was an important port for the British Empire, because of sea-borne trade and travel. The Indian Ocean became a happy hunting ground for German submarines, and raiders. The greatest fear was of the “Emden” which was cruising, preying on merchant shipping: ships were sunk, cargo taken over and also the ships’ crews and passengers who were treated humanely and sent home by various ships that were spared from a watery grave to serve this humanitarian purpose. But, although she entered the popular Sinhalese vocabulary, the “Emden” never did sight Ceylon, though sailing past her. Not so another raider, the “Wolf” which was a raider and mine-layer. The “Wolf” laid mines in the Approaches to Colombo Port which, accounted for the British freighters “Worcestershire” (7175 tons) and “Perseus” (6728 tons) even as late as 1917. Clearly, Colombo had to secure the Approaches by sweeping and clearing mines laid.

But Fleet Minesweepers could not be spared. The Port Commission had to fend for itself and “make do”. The tugs “Samson” and “Goliath” were refitted with minesweeping equipment, and they worked as minesweepers to keep the entrance channel to the harbour clear of mines. Much later, in the early years of the next World War, they were called upon to do the same duty for training the fledgling Ceylon Naval Volunteer Force. So we know what they must have looked like as Minesweepers: “Samson”, for example, was fitted out with Mk.V Oropesa minesweeping gear and Lewis guns and had two Officers, an Engineer and a crew of 37.

And what of my grandfather? He must have carried on, as usual. Minesweeping was a defensive task and the Tugs were not called upon to fight. There were no aerial attacks to fear and danger lay beyond the harbor entrance. He remained a merchant mariner; he was not mobilized: he was just doing his job for the Port. Yet, his work was – as the war work of other merchant mariners – was appreciated.

When the fighting stopped and medals were being handed out, he was not forgotten. He was awarded the War Medal and the Victory Medal both of which were inscribed “DRI. L.O.FELSIANUS. MINE SW.” I still have them, though I had to get the ribbons replaced.

But I was too small to remember much more: he had retired by the time I remember him. He died in 1946, as the second innings of the “Great War” was nearing its end. I must have been about his age when he “ran away to sea”.

He was my first link with ships and wars and seamen: and maybe, just maybe, that’s where the fascination began.