Writing to remember

View(s):Having lost everyone who was nearest and dearest to her in the tsunami of 2004, Sonali Deraniyagala tells Smriti Daniel that her book ‘Wave’ is a memorial as well as a learning process that love never dies

Sonali: Finding comfort in the written word. Pic courtesy Ann Billingsley

Floating on her back, for a moment all Sonali Deraniyagala could see was a perfectly blue sky. Overhead, a flock of storks flew in formation. Later she would write, ‘Painted storks, I thought. A flight of painted storks across a Yala sky, I’d seen this thousands of times.’

A beat and then Sonali was swept back into the nightmare, caught in the maw of a charging tsunami that devoured everything in its path. Before the day was done it had taken from her all those she loved most in the world: her two young sons, her husband, her parents. She was found caked in blood, water and black mud. Her rescuers later reported that she could not stand – instead she was spinning and spinning as if still in the grip of churning water. It would be years before she really found her feet again.

When Sonali began writing ‘Wave’ the first thing she wrote about was being carried by the wave itself – “how utterly bewildering an experience it was, as well as being terrifying and mostly being extremely painful physically. That’s when I remembered things like watching a flock of painted storks fly above me. The strangest things,” she muses, “and when you just write it down they seem even stranger.” Sonali is speaking to me on Skype from New York City where she works at Columbia University. The whole of the book was written there, Sonali curled up in a corner of a bed in an apartment she found on Craigslist five years ago, typing for hours. Writing had emerged as a way for her to make sense of what had happened. “Maybe that’s what allowed me to be so honest…Here was the unfathomable and I was trying to kind of make it comprehensible to myself.”

The memoir has found immediate acclaim, has been reviewed widely and bears on its cover praise from Joan Didion and Michael Ondaatje, both people Sonali considers her literary heroes. Ondaatje’s encouragement in particular was key in her decision to publish such a personal account. “It was gradual, coming around to the notion that I should publish. I was pretty self-conscious of course but then it happened so fast, the publication, that I didn’t have time to dither…” In fact the book was barely edited, and made ready for bookstores in just over a year’s time.

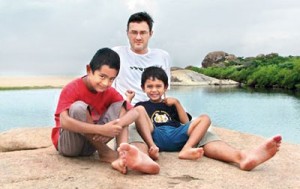

The place they loved: Steve, Vikram and Malli at Yala in August 2004, a few months before the tsunami

It was launched on the 5th of March – a month of birthdays. Her elder son, Vikram would have turned 16 on the 3rd and Sonali herself marked her 50th year. Birthdays and anniversaries are difficult for her, she usually chooses to travel with a friend, picking places that are wild and open. In facing an Artic landscape for instance, Sonali had discovered that there was room for her grief there. That nothing got in the way of remembering. “In a city, a part of you is always ducking and diving from reminders, whereas I think the vastness allowed me to hold it so that the grief could breathe and somehow it worked. I realised quite early on, that I always felt relief there…relief not in forgetting but relief in remembering.”

This time, instead of escaping, she saw ‘Wave’ launched with little hoopla. She had already decided against any kind of a formal event and her publishers supported her decision to largely eschew interviews, T.V appearances, readings and signings. Still, she’s unlikely to ever regain the anonymity that allowed her to work and live beside people who didn’t know her story. Someone who once found herself cringing ‘to be bereft in a way that cannot be imagined,’ now has strangers approaching her in public. “It’s a relief that people know and I don’t have this false identity,” she says. “On the other hand I’m not at ease with the details that people do know. I don’t know how I feel about it. I have to work that one out.”

Most people assume the experience of writing was intended to be cathartic, originating as it did in a suggestion made in a therapist’s office. Instead Sonali found it allowed her to simply be with her family. “By writing I was able to open up memory and to open up my heart really, to be back to who I was with them, and to keep them close.” Much of the time, it was her children she thought about. She writes: ‘Mum. Sometimes I find it hard to believe that I was their mum. Even as I recalled fragments of their birth or recall how I reassured Malli as he peeked from behind a tree, the truth that I was their mother is veiled in confusion. Was it really me who could predict a looming earache from the colour of their snot, who surfed the internet looking for great white sharks and who cuddled them in blue towels when they stepped out of the tub?’ There seems barely room enough to add her grief for her husband and her parents, but add them she must. ‘How hideous,’ she writes, ‘that there should be a pecking order in my grief.’

Though it was what she now wanted above all things, memory hadn’t always been her ally. In the immediate aftermath of the tsunami, Sonali shuddered away from it. The sight of a flower, a blade of grass, of bats taking to the air on a Colombo evening, were unbearable reminders of her family. Like thousands of other Sri Lankan families, she waited for news, unable to entirely deny the possibility that they were alive. It took them four months to identify her husband Steve and younger son Malli’s bodies. They had been buried in a mass grave.

She struggled with a sense of profound shame, of being cursed. She had no answer when one woman wondered what she had done in a previous life to deserve this. She planned her suicide and for a spell became hopelessly alcoholic. “If your whole life vanishes in an instant, at that point you can’t even really feel the grief, the main thing is just terror. If I was alone in a room for two seconds I felt like I was going to pass out. I needed something to numb the terror.” Really, Sonali will tell you, drinking herself into a stupor seemed a reasonable thing to do.

As friends and family became increasingly concerned, a part of her enjoyed letting go so utterly, becoming a crazy person like the one in the poem Vik wrote in class: ‘Craziness is like jellybeans jumping in your head. Craziness is bonkers and bonkers is the best.’ Determined to protect her from herself, her friends stood outside her bathroom door, sat by her bedside as she slept, counted her stash of pills and went walking with her in to Yala without guides. Her friend Lester trailed her as she went out late at night looking for a turtle giving birth out on the beach. Having known him since they were 18 and being beyond any pretence of civility, she remembers screaming at him. “When he came back to England, a lot of my female friends went to see him and they were all crying and saying ‘How is she? How is she?’ and he goes, ‘Stroppy as ever.’ We do laugh about it now.”

That there is laughter and joy in this book comes as a surprise to those who choose not to read it for fear that even second hand, the sorrow will prove unbearable. But there is, and over the course of this interview Sonali laughs more than once, in a warm, deep burble that’s infectious. (“While I was writing it, I thought it was quite funny in lots of bits,” she says.) Her ability to reconcile her loss with a life that goes on is a balancing act, and therapy remains vital. What Sonali cannot do is turn her back on any of it. “We were gloriously happy as a family and that makes the loss even more devastating…It is intolerable, but to feel intolerable pain is worthy of what I lost. That’s the way I look at it. They deserve that, that I feel every bit of their loss,” she says, adding, “It’s actually very enriching in that it opens you to joy and it keeps you alight.”

She faces it head on with every trip to Sri Lanka, making it a point to visit both the site of the hotel and the Yala museum re-furbished to honour her boys. The latter is where her rescuers first took her and a place Vik and Malli often visited. “I think it’s a lovely museum,” she says. “It’s great when you see kids there, pressing their noses against the glass cabinets. It’s so sweet.” The building work overseen by friends and funded by schoolchildren in England has resulted in a memorial that celebrates some of the things Vik and Malli loved best in all the world.

‘Wave’ is a memorial too, in its own way. Only this one is constructed out of words and memories, constructed out of the way Vikram, whispering a reverent ‘malli’ gave a newborn Nikhil his nickname, out of the onion peel and the single eyelash Steve left in their house in Friern Barnet, out of the taste of her mother’s cooking and the smell of her father’s cigar. In reading it you grieve with her, you survive the unimaginable beside her and in the end you are comforted, elevated, made stronger by the knowledge that love endures. It’s what she knows and what she hopes you will see.

“That’s what my big learning has been,” says Sonali. “Love doesn’t die. That’s what made me who I was then and that’s what makes me who I am now.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus