The bigger picture: The artiste and the artisans

How does one describe Tilak Samarawickrema? Architect? Artist? Designer? Or perhaps the sum of all these parts?

Tilak Samarawickrema first came across Ananda Coomaraswamy’s monumental work ‘Medieval Sinhalese Art’ as a young architecture student at the University of Moratuwa in the late ‘60s. Its influence on him would be lasting.

L.S. Samanpura’s Buddha sculptures

He would go on to spend a decade in Italy, soaking in its rich Renaissance traditions and significantly the Bauhaus style, yet return to Sri Lanka to revisit and revitalise the crafts of our ancestors, create modern tapestries drawing on ancient designs whilst also practising as a professional architect.

His new book, a handsome coffee- table volume that was launched this week seeks to draw in all these diverse strands in his life into one absorbing compendium, through a series of articles and reviews that trace this journey complemented by many photographs .

By way of introduction he relies on two erstwhile friends, a Italian critics Bruno Munari and Franco Mirenzi whose early association with him and subsequent appreciation of his work were to prove immensely encouraging. The latter in the preface to the book notes the interconnection between art and architecture in Samarawickrema which can be seen as a leitmotif in his work.

A focal point of the book and indeed one that will be quite a revelation to a new generation less familiar with his work will be his most productive stint with the National Design Centre to which he was appointed as a Design Consultant in 1986. Samarawickrema, perhaps inspired by Coomaraswamy, embraced this opportunity to revive the vanishing crafts of the country and together with his design team traversed the country to unearth skilled artisans. He spent many moons working with them to use the traditional designs and skills to create objects of contemporary interest, whilst also helping them by modernising their technique. ‘Silpa’, the landmark exhibition that was the fruit of their joint efforts brought together some 200 skilled artisans.

It is to Samarawickrema’s credit that he has devoted many chapters of this book to the story of these humble unsung folk. Their accounts are disturbing reminders of how much toil and how little reward their dedication to their craft involves. The pictures of some of their work created in conjunction with the National Design Centre are in contrast, quite stunning in their sophistication, a far cry from the earlier work they were producing. Regi Siriwardena, that eminent critic of yesteryear, writing of Silpa states he could not find one piece that was ugly or lacking in taste, but rather a collection that revealed a wealth of beauty, invention and imagination.

The author hands over the book to chief guest Minister Sarath Amunugama at the launch on Thursday. Pic by Managala Weerasekera

That it was Samarawickrema’s unerring eye for style that resulted in such products is indisputable. He gives an account of how the design team discovered the 70 families in Henawala, a traditional Dumbara mat weaving village languishing in dire economic hardship and the challenge it was to revitalize their craft, strengthening and supporting them till they were in a position to innovate and modernise. The book reproduces for instance on facing pages the deity figures from an ola leaf manuscript and the same figures painstakingly reproduced on Dumbara mats, that after close interaction with the design team the weavers were able to produce.

In one moving account, translated from Sinhala, sculptor L.S. Samanpura talks of the hundreds of Buddha statues he had carved using a variety of materials, yet how he was often unsatisfied with their lack of refinement and how he was able to hone his skills under Samarawickrema’s guidance. Similarly, Samarawickrema’s wife Sriyanthi writes of potter Pubilis of Kelanipura who though making utilitarian ware also had a genius for turning out exquisite figures of bulls, horses and birds, for which sadly there was little appreciation until Silpa. She writes too the story of the Kanatoluwa weavers condemned by caste and hamstrung by poverty. These chapters reveal the sad plight those genuine artisans faced. What became of them? The book provides no answers.

Samarawickrema’s collaboration with the weavers of Thalagune saw his introduction of modern designs to the traditional Dumbara handlooms, his innate ability to fuse the worlds of East and West transposing them to an international audience. The book has some fine examples of the artist’s skill in combining his trademark geometric designs into a traditional theme. Collections of these have been exhibited with considerable success in Norway, Sweden, Germany and Switzerland and at New York’s MOMA ( Museum of Modern Art) Design Store. The book also highlights the constant evolution of his art, the newer tapestries created post 2009, one of which featured on the book’s cover reveals his predilection now for a block design and warmer, softer hues.

Just as his tapestries keep evolving, so too his art – uniquely satirical, it is drawn from a vast panoply: the Sinhala alphabet to French cabaret, bullocks, devil dancers to cricket, the latter his most recent innovation coming in the form of a TV commercial for a leading biscuit manufacturer. His wire sculptures of the figures in his drawings – yet to be exhibited – are also briefly featured.

|

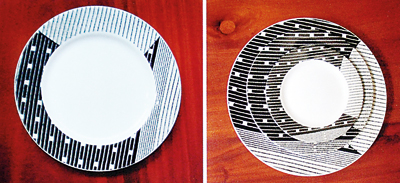

Samarawickrema’s plate design (top) for the Ceramics Corporation and (above) potter Publis’s terracotta figures |

From Samarawickrema the architect, the book presents interesting examples of work done with his own Design Studio and Workshop founded in 1998. A crèche designed for UNICEF in Fort where he himself drew and painted the animal and bird pictures on the walls is in sharp contrast to the modern factory complexes he has built, all steel and glass, sharp angles and cantilevered canopies.

Simple and spare in design, the book is strengthened by a lavish use of photographs which capture the Samarawickrema style more effectively than words. But older readers may find the tiny font size of the text somewhat challenging; some of the pictures also are too small to have an impact.

For those interested in art and design, the book offers an insight into his very distinctive style and the quite significant contribution he has made. Samarawickrema’s creativity, it is clear, is rooted in a firm foundation of knowledge, and spurred by an endlessly questing mind. Forty years old it may be, but his voyage in design is not over by any means.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus