Sunday Times 2

The last hour of Virginia Woolf

Verily, it is the tragic and unusual death that puts many on the Virginia Woolf trail in the first place, the luminous path that leads to the famous

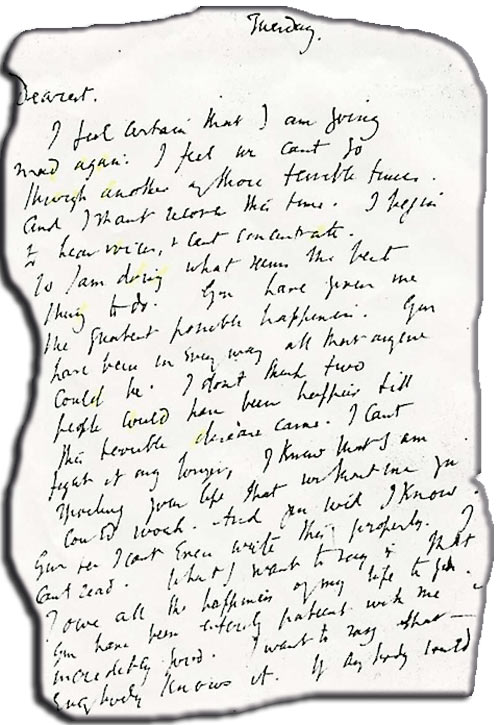

The first page of Virginia Woolf’s handwritten suicide note to her husband Leonard, written on the morning of 28 March, 1941.

modernist books and the famously tragic life. The books and the life have been the subject of hundreds, thousands, of books and articles – biographical and literary, and of an awards-garnering novel and film.

The eminent English writer died 74 years ago yesterday, on March 28, 1941.

The mode of Virginia Woolf’s deliberated death comes as an artistic shock when you first hear about it; the details catch the imagination.

On the morning of her suicide, in her writing cabin in the garden of Monk’s House, the Sussex home of Virginia and Leonard Woolf, the writer penned two notes, one to her husband; the other to her sister Vanessa. She went into the main house and wrote another longer letter to Leonard, and left her home for the last time. She set out on a 15-minute walk, across fields and water-meadows, and on reaching the River Ouse, stopped to fill her pockets with stones, then walked into the river. Left behind on the river bank were her hat and walking stick.

Letters. Stones. Pockets. Walking stick. Hat. River. Death by drowning. Those are the washed-up facts, the pebbles and dry white bones of the writer’s end.

Virginia Woolf, one of the 20th-century writers who brought something new to English Literature with her poetic “stream-of-consciousness” novels, was mentally challenged much of her life. Her battle with madness caused her to endure agonising mood swings, depression and insomnia. She heard voices and was tempted by suicide. When her final state of derangement arrived, she knew she had lost the fight.

The onset of the War and the threat to and destruction of the world she knew, including the damaging of two of her homes by German bombs, would have only intensified her last, killing encounter with insanity.

It was the writer’s death, the newsworthy details, that formed our formal introduction to Virginia Woolf. From time to time, we had heard her name mentioned in background conversation, had seen her books on the shelves of the school and the British Council libraries. She was a vague, wraith-like presence with a haunting name. Virginia Woolf was a name like no other; it contained mood, magic, mystery, even, it seemed, a touch of royalty.

In the Sixties, Younger Brother and self were regular visitors at the home of cousins Stefan and Michel Abeysekera. Their house was round the corner, on New Buller’s Road, in pre-Duplication Road days. The drawing room was filled with the books of classics scholar Vernon Abeysekera, civil servant and diplomat whose last Sri Lankan assignment was as the 36th Government Agent of Jaffna.

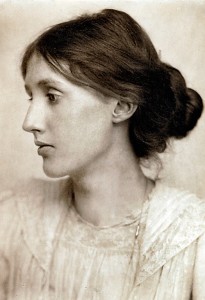

Portrait of Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford

Whenever we picked a volume off the shelf, Vernon’s bookish son Stefan (named by his father after the Austrian poet, playwright and novelist Stefan Zweig) would brief us on the writer and the written work. The all-embracing library had everything, from Seneca to Senator Cicero, Defoe to the full Dickens, La Rochefoucauld to le poète Rimbaud, Sade to Sartre. Our first serious literary tour was conducted by someone two years older and precociously knowledgeable for his 14 years.

A slim, grey-and-white paperback titled “A Room of One’s Own” came to hand. Stefan did his thumbnail bio-sketch of Virginia Woolf. Her suicide seized us. The elemental simplicity of filling pockets with stones, walking into a river and killing oneself did the trick for us; filling pockets with stones is straight out of everyone’s childhood garden, and in our time we had walked into a few streams, if not rivers. The death had shock value, a flash of daytime lightning. There was an instant preteen empathy, a warming up to VW.

The calculated death, composed in the dark of deepening madness, was sad, romantic, shocking, haunting; melancholy and morbid, we wanted more – to hear everything said and written about VW; smitten as we were, we had to read anything and everything written by her.

The bell note of sadness in VW’s end would extend eventually into any and every personal VW experience to come. We read sadness in the books, even where there was gaiety. We sensed sadness in the silken contour of the “V.W.” monogram embroidered in “The Village in the Jungle,” the 1913 novel Leonard Woolf wrote after his seven years in Ceylon. Tree and leaves edging a far-off jungle village threw a mauve-purple shadow on the book’s moonlit dedication sheet. The “V.W.” had been dyed a certain Ceylon hue. Virginia Woolf had by association become part Ceylonese.

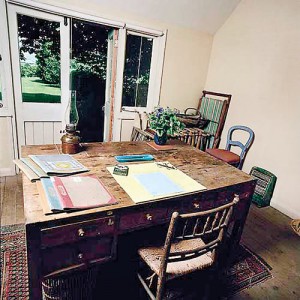

Virginia Woolf’s writing cabin, in the garden of Monk’s House, the last home of Leonard and Virginia Woolf. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe Eamonn McCabe/Guardian

Even her likenesses were strangely Ceylon-like. Looking at certain pictures of Virginia Woolf was like glimpsing in a dream-memory a woman of Ceylon, as reflected in a colonial-era mirror; a wispy presence from a certain remote background, era, social milieu, standing by a doorway, seated by a window. Early VW photo-portraits – she is probably the most photographed female writer ever – show a fine-spun un-English-looking Englishwoman, with beautiful dark silken hair and exquisitely turned features. Her reflective face, with its just-below-the-surface melancholy, is uncannily like portraits seen in old Ceylon photograph albums of mixed-ancestry families. There are at least two faces in our own family album that suggest a VW vintage-mintage, not to mention similar sightings in other related family albums.

Then there’s the name, the magic contained therein.

Of all the names of Western women writers, VIRGINIA WOOLF is surely the most beautiful. Its lettering sequence is magical. The entwined, slim-waisted V-W is exquisitely feminine. Verily like a Woman. Then there’s the V-W of Vine & Wine, a note of special vintage. Held up to the light, the V-W flashes purple, blue, gold, aquamarine.

Virginia Woolf never came to Ceylon, but it feels as if she was here, a long time ago, so numerous are the Ceylon reminders attached to her name.

When Leonard Woolf wedded Virginia Stephen in 1913, he brought to the marriage a background of seven years’ hard-lived administrative life in the tropics. He was fresh from the island experience. His diaries are laden with Ceylon jottings and observations. His mind was overgrown with images of jungle and rural Ceylon, images that would be worked into his Ceylon novel. His body and legs were fit and strong from miles of daily walking in Jaffna and Kandy, where he was a cadet in the Ceylon Civil Service, and Hambantota, where he was made Government Agent. Wisps of Ceylon, like threads of temple incense smoke, must have scented the Woolf marriage.

And long before husband Leonard, there was Aunt Julia.

Julia Margaret Cameron, the pioneer Victorian photographer, was Virginia Woolf’s great-aunt. She came to Ceylon with her husband Charles Hay in 1875, in order to be close to their sons, coffee and tea planters long settled in the “uda-rata” areas of Dikoya and Dimbula. “Dimbola Lodge” is the name of the stately Cameron home in the village of Freshwater, on the Isle of Wight.

In 1935, Virginia Stephen wrote “Freshwater”, a family skit and the writer’s only play, depicting her great-aunt on the eve of her departure for Ceylon, 60 years earlier. Julia Margaret Cameron, who died in Kalutara on the southwest coast, is buried with her husband in the garden of St. Mary’s Church, Bogawantalaawa, in the two coffins they had brought out with them on the voyage out. The cutlery-and-crockery-filled coffins in the ship’s stowage were what we noted on first reading about the Camerons, in the Britannica, back in the Sixties.

A bit of Sri Lankan soil sticks to the shoes if you venture far enough into Virginia Woolf land and stroll along its lanes and byways. When we visited the graves of Julia Margaret and Charles Hay Cameron, we felt we were treading on Virginia Woolf terrain.

Researching Virginia Woolf’s end on the Internet brought us into the room where she wrote her last words. The photographs give a 360-degree view and a sense of what it was like to sit at the plain desk at which she wrote most of her books. The desk faces the garden of Monk’s House, the Woolfs’ last home.

It is only right that an account of Virginia Woolf’s last hours concludes with the writer’s own last words. The final letter she wrote her husband is clear as morning light, as spring water; calm and heart-wrenching in its simplicity, and astonishingly lucid for a statement from a mind clouded over and growing darker by the hour, the minute.

“Dearest, I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that – everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer. I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been. V”