A vindictive king and the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom

View(s):Almost two centuries ago to the very year, the British who were ruling the coastline of Sri Lanka were contemplating the invasion of the Kandyan kingdom. When the invasion did materialise in early 1815 followed by occupation, there was a remarkable lack of resistance for a kingdom that was legendary for its own defence. From a high point in 1803, when the British were routed in their first occupation of the kingdom and when the king of Kandy, Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe was hailed as a god, events had changed dramatically to the point that his subjects were unmoved by his fall.

This article revisits some of the issues surrounding the fall of the kingdom into British hands based mainly on the accounts of Codrington’s ‘Diary of Mr. John D’Oyly’, Geoff Powell’s ‘The Kandyan Wars’ and P.B. Dolaphilla’s account ‘In the Days of Sri Wickrama Rajasingha.’

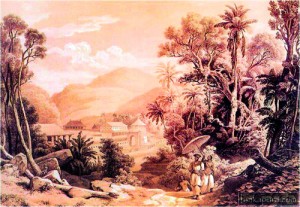

An early painting of the Kandy Palace area. Note the Palace porch and pillars in lower left corner from where the King oversaw the Ehelepola family’s execution. Pic lankapura.com

According to all three accounts of events there was growing discontent among the aristocracy with their ruler. As in any court, the aristocracy undoubtedly wielded great influence. However, a closer look at their role in the fall of the kingdom would suggest that they were more of a permissive factor than an active one in precipitating the downfall. That is to say that they were more than capable of providing ample fuel if the fires of discontent were lit elsewhere.

Court intrigue was not a novel phenomenon; to the contrary it had an existence almost as old as the kingdom. Mutual dislike and constant suspicion between the king and his ministers at court were all well entrenched features. All that seemed novel, if anything, was the last king’s inability to contain the incessant intrigues of his aristocrats.

All the three above sources concur that the unity among the aristocracy fell well short of the solidarity needed to place one of them on the throne. The factions, if any, remained hesitant about bidding for the throne when the old king died without a successor in 1798. Even the overwhelmingly ambitious Pilimatalawwa, chief minister (the Adigar) did not feel sufficiently confident to assert himself directly. That, in itself, should have been a consolation for any king who had to deal only with other resentments of his court. Yet, even then as Powell points out resentment and disloyalty were not necessarily identical – a distinction that previous kings seemed to realise much better.

In fact, in this final period there were only two credible sources that could have replaced the king and the Kandyan aristocrats did not belong in either: one was the Malabar Nayakkar kinsmen of the present king from whose ranks came also the three preceding kings. The other, in their turn, was the British colonial government that ruled the entire coastline and were seeking to extend that rule into the Kandyan kingdom.

Nevertheless, suspicious of his court in those final years 1811-1815, the order of the day was punitive terror under the king. The aristocracy were given ample reminders that they had the legendary joint in their necks. Execution followed execution according to all three sources. Death sentencing of traitors was a universal form of punishment and Sri Wickrama was certainly not alone in ordering them. It was his interpretation and application of this measure to the extreme that proved unsettling to his subjects and to his own circle in court, eventually becoming his undoing as well.

Politically, by far the most noteworthy death by execution in the remaining years of the kingdom was that of the Pilimatalawwa adigar. The adigar has drawn much comment from several sources and it is clear that he was the most redoubtable aristocrat in the court of Kandy, admired and dreaded in equal measure for his sheer ingenuity and shrewdness. After all, it was the adigar himself who orchestrated the succession in favour of an obscure member of the royal family when the last king died. Then again it was he who frustrated Governor North’s attempts to occupy the kingdom in 1803 by exhausting the British troops in trivial pursuits until they collapsed when the final blow was delivered. Even then he distanced himself from the actual massacre and afterward had the temerity to meet again with the Governor with protestations of his innocence.

In 1811 the Adigar was in disgrace and then arrested allegedly for attempting to assassinate the king. A palace servant was asked to murder the king but the deed went unfulfilled. If true, the entire plot was rather naively crafted and lacked the typical finesse of the Adigar’s earlier intrigues. The plot may either have been exaggerated or the Adigar was losing his touch in a very rapid and desperate manner.

The Adigar was beheaded in 1812 along with his son-in-law and co-conspirator, the Ratwatte disawa. Yet his death left a void that was never really filled in court and its consequences are not hard to understand. The removal of so formidable a minister could well have had the effect of unleashing the more violent side of the monarch that became certainly evident in the subsequent years of his rule. It inadvertently also removed a potential obstacle that the invading British would have had to face in their future march to Kandy. Its significance could hardly be lost on the British who had suffered at the Adigar’s hands and especially on John D’Oyly in Colombo who was gathering intelligence about the kingdom.

The next noteworthy execution was that of the Mampitiya Loku Bandara, a son of the late King Kirthi Sri Rajasinghe by a lesser queen. This occurred in 1812 and the charge of treason was contrived against the Bandara. He was accused of consorting with a royal half sister whose offspring could then have a fair shot at the throne. That the Bandara was somewhat advanced in years and almost totally blind were not mitigating factors in Sri Wickrama’s eyes, though his more benign predecessors were known to act with leniency in similar circumstances. To the contrary, D’Oyly notes that the king appeared to be pursuing a vendetta against the family because of their royal lineage.

Mampitiye Bandara’s execution took place, according to Dolapihilla, at the Eastern foot of the Bahirawa hill in Kandy, which faces the town. He refers to it as the “kumara hapuwa” where there grew an ancient champak (magnolia) tree and gives a description of the procession led by a single drummer and two executioners dancing a macabre dance with a corps of the palace guard that usually took convicted nobles to their death. This was also the site of the Pilimatalawwa execution ( D’Oyly’s account though refers to the site as the hunukotuwa near Gannoruwa about 4 miles from the palace). This execution was nowhere as politically significant as that of the adigar but, according to Dolapihilla, it had the equally profound effect of kindling discontent in the Kandyan subjects into whose soul the king had little apparent insight. For the British, it was one more step gained in their eventual advance into the kingdom.

The next noteworthy execution is probably the most renowned in the period of the last king of Kandy – one where the king may well have overreached himself. This was the execution of the new adigar Ehelepola’s family. The tale needs no repeating but it is worth noting that the site of the execution was by the Natha devale near the palace and to the left of where St. Paul’s church stands today.

Unlike the Pilimatalawwa and Mampitiye executions that carried a restrained sense of awe at their tragic downfall, the Eheleopla family’s execution, especially the deaths of the children, revolted all classes of society. In ordering the young children of the family to be beheaded in their mother’s presence and then punishing their mother to a death by drowning at the lower lake formed by the Kandy lake’s overflow, the king had lost all sympathy from his people- a point emphasised in all three sources. Their earlier flickering of discontent had turned to disgust and now was replaced with a new attitude– a withdrawal of their support and a new willingness to see their king removed. Dolapihilla states that when the populace heard that the distraught adigar was allying himself with the British, they all sighed in relief and in their prayers offered their blessings on him. However there was an unintended beneficiary as well. This universal withdrawal of sympathy by the Kandyans towards their king was very much a blessing, however disguised, to the British and their ambitions in the island.

One last execution probably sealed the monarch’s fate: the execution of the Buddhist monk Paranathala Thera. Although, Dolaphilla recounts that there was an earlier execution of the Sooriyagoda Thera, it was generally acknowledged as a lapse of judgement rather than an act of viciousness. Paranathala Thera was charged with violating the code of religious conduct, to which the Chief Priest observed at his trial that it was termination from the monastic order rather than a sentencing that was appropriate; but the king remained adamant. The Thera however did not go silently to his death, instead hurling imprecations at the king and invoking the deities to speed up their divine justice even as he was being taken to his execution.

The prayers of the priest were answered from this world as much as the next; the harsh action of the king served to alienate the Buddhist religious establishment in the kingdom where the clergy time and again had played a formidable role in its affairs. The withdrawal of their support to the throne was another timely factor in the forthcoming British invasion.

With the steady erosion of support for their king from all levels of society in the kingdom, the British were now seen as deliverers from the current oppression. The opportunity was irresistible though the British themselves had recognized the sovereignty of the king with whom they had once entreated on equal terms. The time was ripe to march into the kingdom and the Kandyans had reached out to a foreign power once too often. On January 10th 1815 war was declared and the British army crossed the border at the Sitawaka river. Beyond them in the distance, the mountainous terrain of the Kandyan kingdom beckoned the invaders -for the last time in its history.