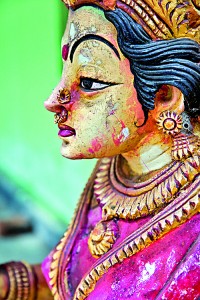

In search of a unifying goddess

View(s):‘Invoking the Goddess’, an exhibition by photographer Sharni Jayawardena and anthropologist Malathi de Alwis focuses on the worship of Pattini-Kannaki, who is common to both Sinhalese and Tamils. Smriti Daniel reports

There is a time in the wake of her great rage – after she has torn her left breast out, after she has called fire down on the city of Madurai – when a widowed Kannaki finds a moment of quiet by the banks of a river. Across from her boys are tussling, engaged in a tug of war. Among their number is Lord Krishna himself and the triumphant side claims their victory with dance and song. The sight recalls Kannaki to herself. Remembering the tug of war she won against her husband Kovalan and their pleasure in their play, her anger begins to drain away. The moment is made immortal in ritual. To this day, the ceremony of horn play, with its exactingly prepared

The duo behind the exhibition: Malathi and Sharni. Pic by Indika Handuwala

instruments, its vattandi or ritual attendants, its earnest players and the accompanying ribaldry and competitiveness, is staged to ‘cool’ the goddess down.

In photographer Sharni Jayawardena’s and anthropologist Malathi de Alwis’s extraordinary new exhibition ‘Invoking the Goddess’,we see how the worship of Pattini-Kannaki takes inspiration from the stories of her life. As a bride dressed in dozens of gorgeously coloured sarees, she unites the community in celebration. She is praised for her chastity and her faithfulness. When she is widowed, her husband wrongfully executed, they mourn with her and echo her unrelenting cries for justice. They comfort her and calm her in the wake of her terrible retribution and welcome her into their homes with elaborately decorated altars as a restorer of fertility and protector of their young. (Interestingly though, as Sumathy Sivamohan notes, they do not name their daughters after her.)

Sharni, who has become increasingly well known for her insightful and striking work in documentary photography, first became interested in Pattini-Kannaki several years ago. As part of Theertha artist collective’s Sethusamudram project, she began studying this goddess who bound both Hindus and Buddhists together in shared belief. (Tamil Hindus know her as Kannaki and Sinhala Buddhists as Pattini.) Malathi shared her interest from the beginning, bringing an anthropologist’s perspective to documenting the various ways in which Pattini-Kannaki was honoured across the island.This is Malathi’s first professional foray into religion – “this has really been a big shift,” she admits. She has previously focused on politics, studying the Mothers’ Front movement for her Ph.D thesis. She recalls even then the fascination of watching the mothers and wives of the disappeared visit the local temple to call down curses on the perpetrators.

Already, the duo have devoted years of travel, documentation and study to this project. Returning to the same site to observe the ritual being played out in consecutive years, they’ve merged into the heat and throng around the Goddess, capturing vivid, colourful expressions of heady faith, documenting shifting alliances in the communities that worship her and the resurgence in the numbers of  her devotees – all this despite being women. It turns out that while the goddess may be honoured, that respect is seldom extended to her female devotees.

her devotees – all this despite being women. It turns out that while the goddess may be honoured, that respect is seldom extended to her female devotees.

In the exhibition, there is at least one black square where you’d expect a photograph to be. In the case of the horn play ritual – ankeliya in Sinhala and kombuvilaiyadu in Tamil – it covers the first week of koluan, when the young men experiment with horn pulling. The next five days are reserved for the experienced men and the process of testing the horns can lead to heated exchanges. Women are banned from participating or even viewing the contest. Issues of pollution – menstruating women for instance are most unwelcome – also dog the rituals. “What does it mean for women today, in a post-feminist age, to find everything is controlled by male priests?” asks Malathi, explaining that there are very few priestesses, the vast majority of whom are marginalised or whose authority never extends beyond the humble shrines in their own homes.

For the two women it presented a bit of a logistical challenge but they chose to meet it by making the most of the events to which they were given access, spending many hours on the ground (thanks to which, Sharni quickly became known as ‘ape madame’ to the villagers.) Photographs taken on previous visits earned their subjects’ trust and enthusiastic cooperation as did conversations with village elders and priests.

Travelling between communities of different faiths, both Sharni and Malathi were fascinated by how a significant number of Sri Lankans didn’t know that Pattini-Kannaki was a “shared deity”, noting that this ignorance was “perhaps an indication of the extent to which the two main ethnic communities on our small island have become alienated”. Many Buddhists for instance remain unaware of Kannaki’s literary credentials as the brave protagonist of the South Indian epic ‘Silappadikaram’ (The Tale of an Anklet). Married to Kovalan, Kannaki is neglected by her husband who chooses instead to consort with another woman, Madhavi. When he falls out with his mistress, he returns to his wife, ashamed but also now impoverished. She offers him her anklets to sell, a way for them to begin afresh. Unfortunately he is mistaken for a thief and wrongfully executed by the king. In her steely determination to claim justice for him, Kannaki sets alight an entire city.

“Everyone has taken off from the ‘Silappadikaram’,” says Malathi. She explains that they have encountered fascinating ways in which it has been localised (everything from caste distinctions to tales of sea battles inserted into the story) or transformed (as in the case of the ‘Kovalan’ told from the perspective of the husband or ‘SilambuKadhai’ or the ‘Story of the Anklet’). Buddhists even shower on her additional births where Pattini is said to be born of a dewdrop or a mango. “They take that story and make it their own,” says Malathi. It’s not surprising then that one of the main challenges of this project has been to capture this incredible and still evolving canon of belief and ritual.

Now, when the two women sit down for an interview with the Sunday Times, they are full of exciting news: The exhibition launch is coming up on the 21st. They will then move it to Jaffna and Batticaloa for longer stints – at the former a conference has been organised to coincide with the opening of the exhibition. Later in the year, they will be hosted in Delhi and New York with the dates yet to be confirmed. Sharni is particularly pleased that anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekere, who wrote the definitive work ‘The Cult of the Goddess Pattini’, has promised to attend the launch. After all, when they first considered embarking on this project, Malathi’s first response was that Gananath had already written the definitive work. What could they possibly add to it?

Their answer to that question has taken the form of a trilingual website and a less academic tone paired with lots of stunning photographs. However, most importantly it has been in the attention they’ve paid to the most recent evolutions in the worship of Kannaki-Pattini. While Hindu reformers in pre-war years had sought to scrub out non-agamic traditions like the worship of the mother goddesses, there has been a resurgence in such activity. “There is still a strong belief; because of the war, those kind of goddesses have also returned,” says Malathi. Writing in her introduction to the exhibition she notes as “a sorrowing yet resilient woman who punishes but also offers succour to multitudes, Kannaki-Pattini is a symbol of hope to the many war widows and women-headed households now constituting a large percentage of the population”. Some rituals rely on reading out entire sections of the Silappadikaram– sometimes over a period of 15 days! – in which Kannaki calls for justice. “It’s clear, she means different things for different people,” says Malathi. In the end, it’s worth celebrating that despite her conflicted past, or perhaps because of it, this all too human goddess has kept her devotees.

Pix courtesy Sharni Jayawardena

| ‘Invoking the Goddess’ will open on February 21and continue until February 23 at the Harold Peiris Gallery at the Lionel Wendt Art Centre, Colombo. The website(www.invokingthegoddess.lk)will also become active on the 21st. The project was supported by the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development. |