Sunday Times 2

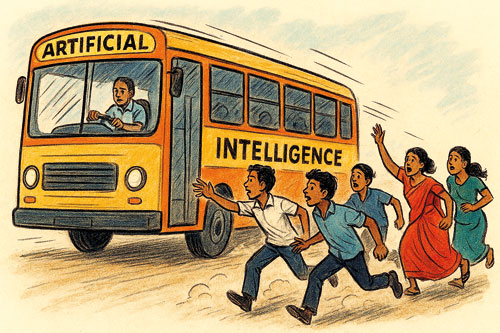

Do not miss the AI bus: Lanka and the fourth industrial revolution

View(s):By Yasantha Rajakarunanayake and Chula Goonasekera

On a Sunday afternoon, a packed Zoom global audience (https://youtu.be/ISfnDoTJ5YI) listened as Dr Yasantha Rajakarunanayake posed a deceptively simple question: What if Sri Lanka didn’t arrive late this time?

The Sri Lankan–American physicist, computer scientist, and data scientist was speaking at the LEADS Forum, drawing on decades of work at the frontiers of artificial intelligence (AI). His message was urgent but hopeful. AI, he argued, offers Sri Lanka a rare chance to leapfrog—not inch—into global relevance. Miss it, and the country risks repeating a familiar story of delayed entry and lost opportunity.

Illustration by Microsoft Copilot

A history of arriving late

Sri Lanka has lived through three industrial revolutions, but never quite on time. The First Industrial Revolution of the late 18th century, driven by steam power and mechanisation, touched the island early—largely through colonial rule rather than local innovation. The Second Industrial Revolution, powered by electricity, telecommunications, and mass production, arrived late. The third, defined by computers, microchips, and the internet, arrived later still.

Those delays were not accidental. As was noted, national priorities were often diverted toward political consolidation and prolonged internal conflict, rather than sustained investment in education, technology, and innovation. The result is visible today in economic fragility and persistent inequality.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution—centred on artificial intelligence, cognition, robotics, quantum technologies, and intelligent systems—is unfolding now. And for the first time, Sri Lanka may have the conditions needed to join it early.

Why AI changes the equation

Artificial intelligence is not just another technology layer. It is a general-purpose capability that reshapes the interaction among labour, capital, and knowledge. From architecture and agriculture to tourism and healthcare, AI tools dramatically increase speed, accuracy, and scale.

For developing countries, this matters profoundly. Unlike previous revolutions that demanded heavy physical infrastructure, AI thrives on human capital—skills, curiosity, and connectivity. Sri Lanka’s strengths are clear: a literacy rate of around 92%, a young population hungry for education, and a large, engaged diaspora willing to mentor, invest, and collaborate.

“AI is a discovery, not just an invention.” This statement highlights that AI’s power stems from uncovering the fundamental mechanisms of intelligence, which appear—perhaps unexpectedly—to align with machine-learning algorithms. The deep parallels between human cognitive structures and computational logic suggest that the field is revealing a pre-existing blueprint of intelligence rather than merely creating a new technology. Many major breakthroughs—such as large language models, machine learning, and pattern recognition—have emerged from insights into how intelligence itself functions. Increasingly, these tools are accessible through open-source and low-cost platforms, lowering barriers that once favoured only wealthy nations.

Work, wages, and unease

No discussion of AI is complete without addressing fear—particularly fear of job loss. History offers perspective. Each industrial revolution displaced certain jobs but ultimately created more work, new professions, and higher productivity. Remote work itself, now commonplace, is a legacy of the digital revolution.

AI may follow a similar path, but with sharper short-term disruptions. In medicine, for instance, AI-assisted radiology lowers costs and expands access but also changes how specialists work. Education cycles may compress, reducing the years required to gain certain qualifications. Proposals such as an “AI tax” to support displaced workers—floated by figures like Bill Gates—are no longer theoretical.

The lesson is not to resist AI but to govern it. Ethical oversight, transparency, and legal frameworks are essential, particularly as AI systems can “hallucinate” incorrect outputs when trained on imperfect data. Left unmanaged, the benefits of AI could concentrate narrowly. Managed well, they could be broadly shared.

From brain drain to brain gain

For decades, Sri Lanka’s most reliable export has been its people. Engineers, doctors, academics, and IT professionals, and some as domestic workers, have migrated physically, sending home remittances but leaving behind gaps in expertise and social cohesion.

AI enables a different model: virtual migration. It is increasingly realistic now for Sri Lankans to work remotely for global firms—from Fortune 500 companies to research labs—while living in Galle, Kandy, or Jaffna. Income is earned in global currencies; spending happens locally. This shift could reverse brain drain without forcing families apart.

By introducing a dedicated 1–6 month “reverse visa” for foreign professionals—a new digital nomad visa category that permits employment while safeguarding local jobs—Sri Lanka could generate a substantial economic boost. These hybrid tourist-workers, who earn income from overseas employers, would inject significant foreign exchange into the local economy through extended stays in hotels and rental accommodation, while also supporting the food, hospitality, and wider service sectors. In addition, such a policy would attract foreign professionals who collaborate with local talent, strengthening knowledge exchange while further enhancing the tourism ecosystem.

Real-world impact, sector by sector

Apparel: Generative AI can compress design cycles from weeks to hours. Designers describe ideas in natural language; AI produces patterns, 3D samples, and variations optimised for local fabrics and compliance standards. Speed-to-market becomes a competitive weapon, positioning Sri Lanka as an “instant fashion” hub.

Education: The country’s tuition-driven education culture prioritises memorisation over analytical thinking and problem-solving. Yet AI has already internalised much of the world’s information. The human advantage now lies in asking better questions, synthesising ideas, and solving complex problems. AI tutors can deliver personalised, Socratic-style learning to a student in rural Monaragala as readily as to one in Colombo—helping to bridge both knowledge and language gaps.

Healthcare: In villages where doctors are scarce, AI-assisted triage kiosks can record symptoms, flag critical cases, and support telemedicine. Predictive models analysing rainfall and mosquito density could forecast dengue outbreaks weeks in advance, saving lives and reducing costs.

Agriculture and Tea: AI-powered image analysis detects crop diseases early using smartphone photos. Precision fertilisation reduces waste and costs by tailoring inputs to soil and weather conditions. Yield prediction models help farmers plan, negotiate, and stabilise income.

Tourism: Imagine every visitor arriving with a personal AI guide—one that adapts itineraries in real time, suggests hidden experiences, explains cultural practices, and reroutes plans when rain falls in the hill country. Personalisation increases satisfaction and spreads tourism income beyond overcrowded hotspots.

Youth as builders, not just users

Perhaps the most powerful message of the forum was directed at young people. Do not just consume AI; build with it.

The problems are visible everywhere: erratic bus schedules, waste management failures, and language barriers for farmers. With low-code tools, basic programming skills, and community feedback, these frustrations can become scalable solutions. A tool built for one village may apply to thousands across Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The challenge set was bold: by the end of this year, Sri Lankan youth should aim to build 1,000 AI solutions to real local problems—not as academic exercises, but as deployed tools that improve lives.

Education that learns, too

For AI to succeed nationally, education systems themselves must become adaptive. Static curricula updated once a decade cannot keep pace with technologies evolving yearly. Degrees may need to be shortened; assessments may need to shift toward AI-assisted evaluation that is faster, fairer, and less prone to corruption.

With mobile phone subscriptions already exceeding the population, smartphones offer a practical platform for mass upskilling. The digital divide, once assumed insurmountable, may be narrower than expected.

At the same time, regulation must evolve alongside adoption. Investing heavily in rigid systems risks rapid obsolescence. Flexibility, diversity, and continuous reform are safer bets.

The road ahead

Artificial intelligence is neither saviour nor villain. It is a tool—powerful, amplifying, and shaped by human intent. Used wisely, it can help Sri Lanka convert long-standing vulnerabilities into strengths: turning brain drain into brain gain, remoteness into connectivity, and limitation into innovation.

The bus is already moving. For Sri Lanka, the question is no longer whether AI will change the world, but whether the country will be on board when it does.