Sunday Times 2

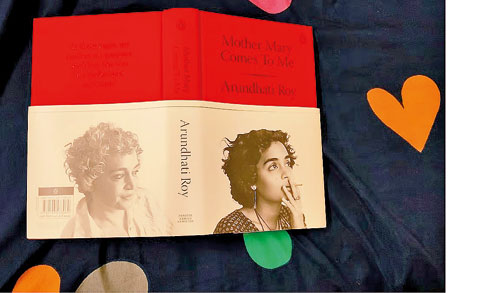

Arundhati’s Mother Mary Comes To Me – a critique of contemporary Indian social ethos

View(s):Reviewed by Mahinda Hattaka

Arundhati Roy, best known as a controversial contemporary Indian writer, was inspired to write her memoirs by her mother Mary Roy’s death at an unexpected moment that left her shocked and devastated. In a completely detached manner, the book vividly depicts her attachment to the mother, a rebellious and daredevil woman. She called her mother Mrs Roy, as she had been taught since her student days.

But ‘Mother Mary Comes To Me’ is not a eulogy. It is a cruel and unapologetic incision of the umbilical cord of the love-hate relationship that sustains her in victories and innumerable downfalls. Mrs Roy, as she usually calls her mother, never showed her love or attraction to Arundhati overtly or, in a sense, covertly.

She encouraged Arundhati to write from her school days. When Arundhati came home from the school – actually, they lived in part of the school which Mrs Mary started on her own – her mother asked why she was in a low, downcast mood. Then Arundhati recalled how she was scolded and humiliated by her class teacher for giving the correct answer to a question posed to her. Then Mother Mary calmly asked her to write down the story on a piece of paper. Though the few sentences she wrote made no sense, as she recalled later, Mother kept it as a precious piece of writing to the very end of her life.

Her mother’s love and affection did not prevent the use of most foul words to thwart Arundhati. She says, “The insults washed over me like a tide. Apart from the usual ones, the additional theme, of course, was ‘whore’ and ‘prostitute’. It went on forever….”

Arundhati is explicit, and baring everything in her dealings with family members and the people around her makes her writings magical and illuminating to the reader. She sees her mother’s behaviour or the attitude toward her emanating not from any lapse on her part but from her wrath against motherhood itself. Therefore, she tried to surgically excise an incident from its circumstances and look at it dispassionately, shorn of excitement. “As though she were someone else’s mother and as though it were not I but someone else who was the object of her wrath.”

What made reading Arundhati exhilarating and exciting is the poetic but objective way of looking at seemingly ordinary and simple things differently. For instance, the distance covered to come to Delhi from Cochin by train was counted not by kilometres or any other system of measuring the distance but by days and nights. She spent three days and two nights to reach Delhi. This kind of figurative thinking is abundant throughout the book.

Most interesting is the way she visualises the language. We all use language, whether it is English, Hindi or any other, as a medium of communication. Language is an already existing phenomenon. We have to depend on it to lead a meaningful life in society. But Arundhati saw it also differently. ‘’I wanted to test myself to see whether I could find a language, a writer’s language, to write about the Narmada and the tragedy that had befallen it in the way I had found a language about Ayermenem and the Meenachil. Could I write about irrigation, agriculture, displacement and drainage the way I wrote about love and death or about characters in a novel?” she asked.

The style of the language she used in her first and award-winning novel, God of Small Things, is totally different from the style and nuance of the language she used in her first political (and controversial) essay on the nuclear ambition of the BJP government, End of Imagination. She firmly believes the language should be modified, moulded and created to cater to the needs of the picture she visualises in a certain context. Just as an artist selects the brushes, colours and the canvas to create a picture she or he imagines. Even though she is writing in English, the way she is using the grammar and the syntax is not the ordinary run-of-the-mill type. Even the name of the book, Mother Mary Comes To Me, can be interpreted many ways. For a Christian, Mother Mary denotes religious feelings of affection and devotion and virginity. But she uses it in a different hyperbolic environment. The name of her first novel, God of Small Things, is also sort of a puzzle. For a resourceful person can visualise it in many ways.

Literature is a medium, she thinks, that compels a reader to understand and react to the world around him more penetratingly and critically. At a public reading session on her book held in Kerala, her native place, a person from a small village came up to her to get her signature on a book he purchased. She says, “It made me realise now literature can join humans in a bond of quite intimacy in a way almost nothing else can.” It reminded her Estonian translator of her book God of Small Things, saying, “Your book is about my childhood.” A Jewish publisher said, “We’ve all got aunts like Baby Kochamma.”

She confesses that the inspiration to write this memoir mainly comes from her love and devotion to her mother. That love and devotion compels her to write about the contemporary issues that bedevil Indian society and the world at large. Most interestingly, these polemical writings are not different from her literary creations. Her Italian friend and great writer John Berger wrote her after reading her essays about the Narmada dam, saying that her fiction and nonfiction walk you around the world like your two legs.

When the Indian Supreme Court vacated its earlier order stopping the work of the Narmada reservoir consequent to a petition filed by a group of civil activists led by Medha Patkar, they felt they had lost the momentum and the thrust of their movement. To galvanise the public support to fight against big capitalists hell-bent on exploiting natural resources and to restore the rights of indigenous people and the rural poor, they had to start the protest campaign anew. One of the activists of the movement, Himansha, extended an invitation to Arundhati to visit the valley and write an article about the ecological devastation going to happen and the consequent human suffering. She travelled the length and breadth of the valley and wrote an explosive article in her usual sarcastic and corrosive style, which resulted in summoning her to the Supreme Court for insulting the judiciary. This is the first of many contempt charges she faced, mainly because of her writing exposing the undemocratic and discriminatory nature of the prevailing social and political order. It earned her a new epithet, ‘activist writer’.

Her mother, a fighter of indomitable courage and steadfastness, was a strength and inspiration to these polemical writings. She says, ‘Mother hovered over me like an unaffectionate iron angel.’ But the judiciary of India is not that sympathetic to her uncompromising criticism of the prevailing social injustices and the institutions which sustain them. The Supreme Court of India imposed a fine and prison sentence for one day for the contempt of the court.

Mother Mary Comes To Me is not a chronology of events and reminiscences but a deep and uncompromising analytical study of present-day Indian society and the social order that is undergoing rapid changes in the name of modernisation and innovation that may shake its roots, set against the background of her mother’s and her own living experience.