Rio awash with a sea of change

Firi Rahman’s ‘Taste Karaththe’. Pix by Priyanka Samaraweera

The ocean has always been shrouded in mystery, symbolising many things from turmoil to trade to tranquillity. The theme for this year’s edition of Colomboscope (January 25-31) was ‘Sea Change: As Tides Turn’, and addressed the urgencies of a rapidly changing coastline and the complex negotiations that have to be carried out between communities and the capitalistic ambition.

Held at the derelict Rio Cinema complex, Colomboscope brought together 30 artists both local and international to share their own perspectives on development and relationships to the coastline.

The reason for using the Rio as their main venue, according to curator Natasha Ginwala, was because the space is almost like an observatory.

“From the top, you’d understand exactly what’s going on in terms of the dynamic of development and displacement,” she explains.

Walking into the dimly lit space, the first exhibit to greet you encapsulates this notion perfectly. Firi Rahman’s ‘Taste Karaththe’ responds to urgent shifts occurring within Colombo and the lived impact of gentrification in Slave Island.

He brought in the concept of sea change by creating animated drawings of sharks, boats, coral reefs, lighthouses on rotating fans within a food vending cart reminiscent of those around Galle Face. Firi wants to spread awareness through art, and to tell the story of the neighbourhood from oral testimonies he has collected from people in the area.

“We must notice the changes occurring around us and then think about it,” he explains adding that if small habits are changed, it can make a difference.

“We must notice the changes occurring around us and then think about it,” he explains adding that if small habits are changed, it can make a difference.

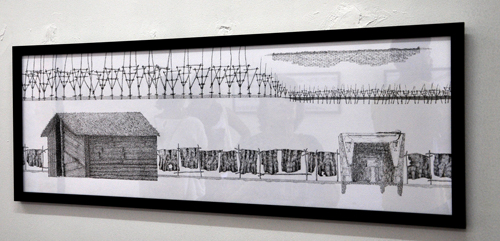

A few floors up, you’d find Jasmine Nilani Joseph’s ‘Unveiled Barriers’ – an exhibit construed entirely with a rotring pen on paper. Jasmine is a visual artist whose main focus is on drawing and its expanded relation to lived histories. Her own story plays out in her work through accounts of forced displacement and the violence faced during her childhood in her hometown of Vasavilan in Jaffna during the war.

Her work also spoke of how the sea can be a barrier itself. “The invisible lines are the barriers,” She explains. It portrays the Indian and Jaffna fishermen’s conflict over poaching and fishing, migrants travelling to Australia in a boat and the dangers they face.

The festival’s focus remained on collaborative works, hosting workshops with students, and opening up the festival to all kinds of audience groups and for international artists to integrate with the local arts scene.

Natasha explains the exhibition wasn’t limited to painting, sculpture and photography. Rather they pushed to include more experiential works that have to do with smell, sound and film, to introduce them to the broader Sri Lankan audiences.

Jasmine Nilani Joseph’s ‘Unveiled Barriers’

One such unusual exhibit was by Sissel Tolaas, a Norwegian artist, smell theorist and chemist who has been working with coastal scents for the past few years. Her exhibit featured smells from the Sri Lankan coasts captured in cans, that looked to trigger memories and reimagine our relationship to the coast and the question of preservation.

Despite the broadness of the theme, there was particular effort made to magnify the local community’s issues with displacement due to port developments.

The festival has since built up an interdisciplinary large-scale dialogue across very different communities. The organisers make it a point to make the festival accessible, by including artists from the North and the East, and inviting 150 art students from Batticaloa to explore the festival for example.

“Those are all things that make it have the kind of impact it needs to have,” Natasha says.

That’s what contemporary art is today – according to Abdul Halik Azeez, whose own body of work as part of Colomboscope focuses on sourcing images though Instagram about the exploding image of Sri Lankan paradise that is highly consumable for foreigners who have not experienced the micro-realities that it faces every day.

“It’s not about aesthetics anymore,” he explains. “It’s about ideas, concepts, moving people and talking to your environment and talking through the issues that are going on today in a different angle.”