Writing about a world he knows all too well

Close without touch. That was the only love permitted, though it was deeply felt among our own. We borrowed idioms and shopped American verses. In our caustic speech we threw out platitudes, in our guts our feisty wit. It was like we lived upon jagged teeth in the dark, in this bone-cold London city. A young nation of mongrels. Constantly measuring ourselves against what we were supposed to be, which was what? I couldn’t tell you.

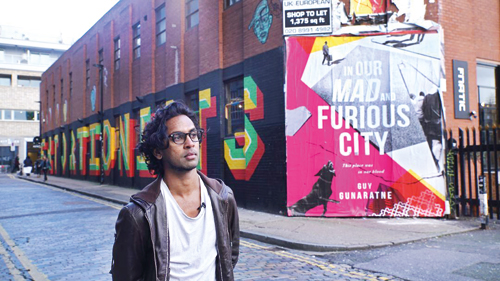

Guy Gunaratne: A dissonant portrait of London

As children of immigrant parents, street jargon disguised as self-assured hubris is the one thing close friends Selvon -an adrenaline-fuelled amateur athlete looking out for his friends, Ardan -an aspiring musician who dredges up courage from unscripted rhymes, and Yusuf -a ‘bredda’ seeking to extricate himself from a community he doesn’t recognise anymore, have in common.

Addressing first the many frictions within a community of those ‘who have an elsewhere in their blood’ Guy Gunaratne sets the backdrop of his debut novel within the tense confines of London’s Stones Estate – a violence-prone neighbourhood now being thrust into an even more venomous cauldron of dissonance.

Ever since it first rolled off the presses in April, In Our Mad and Furious City has been lauded by contemporary literary greats Ali Smith, Stephen Kelman and Kit de Waal, and has been reviewed glowingly by The Guardian, The Observer, and The Irish Times. Most exciting however, is that Gunaratne’s first foray into publishing was longlisted -alongside Michael Ondaatje- for this year’s Man Booker Prize.

Speaking from his current home in Malmö, Sweden, where he is presently taking in from afar, the appreciative nods from across the publishing world, Gunaratne says he was -in this order -shocked, humbled, and now admittedly the most content he has ever been in his life about this new ranking.

The tellings of Selvon, Ardan, and Yusuf are joined in this swirling portrait of a fury-tinged city by the retellings of Nelson -once a wide-eyed immigrant from Montserrat, now a frail elder fretting over the future of his son, and Caroline, an Irish immigrant single mother still trying to scavenge a future in the city she has chosen to call home.

The world Gunaratne writes for all five is a world he knows all too well. As the child of immigrant parents himself, there is no better custodian for their story. That the characters, both young and old, have attributes of his own and his parents’ experiences is unintentional, he says. Though admittedly, one can’t help but infuse a story so close to home with familiar cadence.

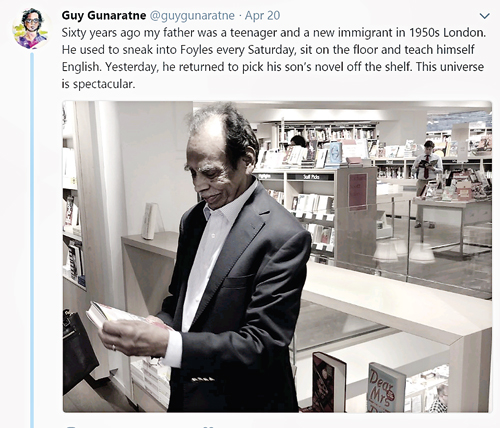

In keeping with the conversation on the inheritance of generational stories, Gunaratne speaks and has written endearingly of his retired father who “migrated from the country of his birth, to this country of mine” as a 16-year-old, working through several menial jobs before finally settling as a clerk at the Sri Lankan High Commission in London.

Six decades later, his father is now basking in the afterglow of his writer-son’s success.

In a tweet that went viral -for all the right reasons- only a few days after the release of his book, Gunaratne shared a photograph of his father returning to Foyles -the bookstore he used to frequent to teach himself English many years ago, only to pick up from the same shelves a novel written by his own son.

Unlike his parents however, Gunaratne grew up in North West London, and was a documentary filmmaker and journalist covering human rights issues across the world. Now in his 30s, he says that for as long as he can remember he has been writing, but it had always been “just background noise”, preferring instead other creative efforts as an outlet for his political inclinations.

As it turned out, it was, Gunaratne confesses, the brutal slaying of British soldier Lee Rigby in 2013 which finally compelled him to choose pen over video camera to tackle the themes of racism and violence racking his home city.

From a novel that opens with the killing of a ‘soldier-boy’ by an alleged extremist, one would assume that the pages of In Our Mad and Furious City too would take a predictable trajectory akin to a Mohsin Hamid-Riz Ahmed’esque saga.

However, as the dust settles on the actual incident, and the focus narrows in on the aftermath and its effect on the lives of the narrators, we find ourselves in a disconcerting place; held hostage by the very unsettling sentiment that chilled Gunaratne’s own blood when he first watched for himself the grisly clip of a blood-stained Michael Adebolajo in the real life killing that spurred this book.

“…to us he looked as if he had just rolled out the same school gates as us. He had the same trainers we wore. Spoke the same road slang we used. The blood was not what shocked us. For us it was his face like a mirror, reflecting our own confused and frightened hearts.”

“The lesser interesting thing for me to do would have been to write about how a young man becomes radicalised,” justifies Gunaratne. “My perverse compulsion was instead to ask the same question I was made to ask myself then: Why would I see myself in such a monster like that?”

While the plot for this 48-hour chronicle is clear, and its closing insistent, it is hard to extricate one or even just a few themes which the story can stake sole claim to. Violence and racism volley with friendship and brotherhood. Despondency fist bumps survival, while the dregs of extremism gain momentum as they roll along unfettered, from one generation to the next.

“Dissonance, I have always felt, is necessary for any city. Growing up, I knew nothing else but multiplicity; you’re very aware and sensitive to friction-ridden experiences along with all the other narratives swirling away. It seems antithetical for me to describe that world without confronting these disturbances. There are books about other cities such as this that have a rich multi-cultural experience, but shy away from the differences between us, and I feel that to do that is to really do a disservice to what multiplicity really is.”

That the book can be misconstrued as something humourless, bleak even, is a contradiction Gunaratne is quick to dismiss.

“London too is wonderful, is beautiful, and is capable of something that could be so hopeful and enriching. But only in acknowledging what makes it ugly, will you have truly earned what there is to love about the city.”

The tweet about his father that went viral for all the right reasons

And so, the story goes: Nelson and Caroline scavenge for just one halcyon day in their spar between the current tide of violence and their recollections of yore. And alongside them, in a narrative that finds them inextricably linked, Gunaratne’s young protagonists too, attempt to overcome their present-day altercations with bloodshed. All for it to become increasingly evident that living under the shadow of extremism in its many guises, can alter more lives than just the hood’ied or skull-capped.

Gunaratne does not, infer any panacea for his many provocations. He is content enough with just the exposition of these themes. “I’m going to explore this feeling that I have, and you can come along with me. At some point that self-reflection is enough. The best novels are the ones that have you asking the questions, rather than giving you all the answers.”

Above all, In Our Mad and Furious City is a masterful balancing act. Profound paradigms leap off the pages through what is at first glance, unschooled, coarse prose. The narrative, like a hot piece of iron, is passed on from character to character in tune to a curiously appealing backdrop of grime-induced harmony.

The real artistry however, is in that even the reader accustomed only to the glossier side of Britain’s metropolis-in-chief can stake ownership not just to a newfound literacy in vernacular idiom, but a begrudging understanding of what it means to be living in such close proximity to violence. Gunaratne plays both the role of storyteller and Pied Piper, unravelling a stimulating narrative, while almost hypnotically evoking the rhythm of a mad and furious city.

So here it all is, this London. A place that you can love, make rhymes out of pyres and a romance of the colours, talk gladly of the changes and the flux and the rise and the fall without feeling its storm rain on your skin and its bone-scarring winds, a city that won’t love you back unless you become insoluble to the fury, the madness of bound and unbound peoples and the immovables of the place. The joy.

While awaiting the results of the Man Booker shortlist, Guy Gunaratne is currently working on his second novel, and “can’t think of anything more beautiful to be doing with my life right now.” He would tell us about it, but has been banned by his wife from doing so.

He hopes to soon be able to visit again the island that gave birth to his parents.