Memory makes us what we are as individuals as well as societies

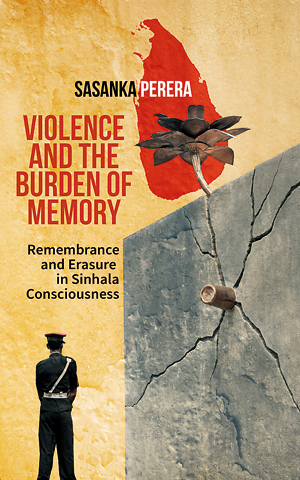

Professor Sasanka Perera who received both his PhD and Masters in Social Anthropology from the University of California, Santa Barbara, is an anthropologist associated with the Colombo University at first and now, with the South Asian University in New Delhi, of which he is Vice President. He is also that rare Sri Lankan academic who publishes constantly and consistently, researching on Sri Lanka and engaging with issues currently needing much focus and attention in this country. His absence from Sri Lanka in recent times makes it easy for his work to be easily missed here and in July 2018, a discussion organized by the Social Scientists Association was held in Colombo about his book Violence and the Burden of Memory: Remembrance and Erasure in Sinhala Consciousness which was published by Orient Black Swan in 2016. This is an interview related to that work.

- This book is the result of fourteen years of work. What made you undertake this study?

I am old-fashioned when it comes to research. I can’t be rushed by publishers, by funders or by employers beyond a point. Besides, this work has to do with people’s emotions, frames of mind and anxieties. By definition, this kind of work takes time. In our kind of social, political and intellectual circumstances, academics play multiple roles simultaneously. We simply cannot take leave for a few years, undertake fieldwork, and then sit in some nice place and write. That kind of luxury of the Ivory Tower is not a privilege some of us in this part of the world enjoy. In my own life, all these things have impacted on the time it has taken for the book to come out since the initial work began.

I am old-fashioned when it comes to research. I can’t be rushed by publishers, by funders or by employers beyond a point. Besides, this work has to do with people’s emotions, frames of mind and anxieties. By definition, this kind of work takes time. In our kind of social, political and intellectual circumstances, academics play multiple roles simultaneously. We simply cannot take leave for a few years, undertake fieldwork, and then sit in some nice place and write. That kind of luxury of the Ivory Tower is not a privilege some of us in this part of the world enjoy. In my own life, all these things have impacted on the time it has taken for the book to come out since the initial work began.

Why did I undertake this study? One can also ask, why not? My response however is somewhat complicated. This is about how memory works among the Sinhalas. I thought as a member of society, I needed to know how people remembered and forgot. This was also about formalizing as knowledge things I had seen going on all around me for a very long time. This had no developmental agenda. It only had an intellectual one.

- Your book deals with memory and erasure. Why is memory important to a society?

Well, one can always say memory is not important. In fact, many people have told me time and again over the years, that it is best if one forgets unpleasant things. My thinking is different from this kind of escapist sentiment. For me, a person without memory or a society with a ruptured or consciously altered sense of memory, are living in an illusion. Their lives would be incomplete or even false. Memory and a sense of the past makes us what we are as individuals as well as societies. But memory should also not be a burden beyond a point. It should simply anchor us to the present and the past, but also should allow us to traverse into the future. But as a realist and as a Buddhist who is familiar with the notion of anitya, I also understand well that everything changes and nothing is permanent, including memory.

In this context, what I have tried to understand is how memory works in the context of the trauma that war has brought to us, and when erasure sets in, and how we as a people deal with our collective past.

- This is a comprehensive study of monuments in Sri Lanka — either state sanctioned, group initiated, privately built or visually represented by artists. Given, as you yourself say, the Sri Lankan, especially Buddhist, cultural practice of remembering through rituals like the giving of alms rather than visiting monuments to grieve over someone, most of these monuments are falling into disuse or not being utilized the way they were designed for, according to your work. Why was it important to you to document this phenomenon?

Fundamentally, this is a study about remembering and forgetting. For me, things like monuments and artworks dealing with violence are simply instruments of memory as are the kind of religious rituals you refer to. True, many of the private monuments including many bus stands and tombstones erected in memory of people killed in the war have gone into disuse. LTTE monuments have completely vanished from the landscape. Military monuments still function as they are linked to calendar rituals performed by their creators. In other words, they work because here remembrance is institutionalized. But memory everywhere is very fragile. It is this sense of impermanence and fragility of memory that the status of these monuments and the practices associated with them tells us.

I think even when it comes to religious rituals of memory, the emotional distance between the living and departed also tend to diminish somewhat over time even if these rituals might continue year after year. They become routine.

For me, it was important to document these because this is part of our collective history. And this kind of understanding history or our past does not find much acceptance in mainstream writing of history or even mainstream sociology. After all, I have looked at the memory of ordinary people, not political leaders or the powerful.

- Your work in this and other documents, research into the visual art of a particular time in this country. You have laid out clearly why this creative practice might itself face erasure and not be remembered by future generations. Do you think there is any way in which this can be avoided, and what the artists narrated could be made to impact the generations that come after us?

The work of visual artists engaged in what might be broadly called ‘political art’ is one way in which memory is transacted. Why I have said this expression of memory is threatened with erasure is because we have no systems of seriously collecting and preserving our artwork for the future. Some of these works might remain in private collections. Others might be documented in books like mine. But most will lapse into erasure. I don’t think there is any way to avoid this at the moment simply because our country does not have a systematic system of art preservation. As a result, we do not have the same benefit as some developed countries with sophisticated systems of galleries and museums have, where art in many instances become a reflective source of history.

- What role do you think anthropologists and sociologists can play in Sri Lanka’s post war society?

Prof. Sasanka Perera. Pic by Pala Pothupitiye

People with this kind of disciplinary training at a global level can ideally play multiple roles. One problem we have in Sri Lanka is that the kind of sociology or anthropology training offered by our universities, in my assessment, is nowhere near where it should be. At one level, this training does not offer trainees the background to be good university teachers in the global scheme of things. At another level, I am not sure if this training offers anything useful for the larger labour market either. In this kind of grim situation, I am not sure what people with this kind of local training can do barring a few exceptions.

- Many articles and research work about the problems here are done in English. How effective do you think such work is, to bring about a change in this country? Should there not be an attempt to bring these ideas to the Sinhala and Tamil- speaking public?

You can look at this in two ways. Scholarship does not necessarily have to lead to social transformation. It is primarily about knowledge. But if it has to lead to social change, then, it has to reach a wider readership. It is in this latter sense what you have asked needs to be answered. The world of scholarship is not only a national one. It is also global, and that world cannot be reached via Sinhala or Tamil. A knowledge base that is too national in terms of focus, approach or language can be too parochial. It is also about time our academics and thinking people in the country acquire the ability to access knowledge produced in global languages. Not everything will ever be produced in our own languages. On the other hand, I strongly believe crucial works produced by local and foreign scholars that are relevant to us need to be available to our people in their own languages. But there has to be a formal institutionalized translation system to make this happen as can be seen to some extent in Japan and China. Though my own output in Sinhala has diminished in recent times due to my present location and circumstances, I still try to do this whenever possible.

- You are now working as a Dean in South Asia University, Delhi. Can you give a brief description of how you have come to be there?

I am actually the Vice President of the University in addition to teaching sociology. I resigned as Dean of Social Sciences on August 31 after nearly seven years. I honestly believe scholars should engage in scholarship and teaching rather than dabbling in administration. But when I came to South Asian University in 2011, there were no senior academics in place. Even today, the situation has not improved much. So I had to take up some of these administrative responsibilities quite reluctantly, which I had successfully avoided at the University of Colombo, for most of my career.

I was interested in the idea of the South Asian University for a long time and had close associations with some of the scholars in the region who had initially mooted the idea. So when the university actually got off ground in 2010, I was quite keen to be part this experiment. It was expected to be a regional university funded by the member states of SAARC where knowledge was to be offered without the hurdle of militarized borders.

My initial idea was to come to Delhi for five years, help set up the sociology programme, and then go back. But despite this being a state-funded international university to which Sri Lanka also contributes, my request for leave fell on deaf ears. At the same time, many of my colleagues got easy opportunities to take up political appointments, which had no academic merit. So, I resigned. Sometimes in one’s life, one must take risks if it offers worthwhile challenges and possibilities broadening one’s intellectual horizons. In retrospect, I think resigning from Colombo is perhaps one of the most sensible things I have ever done in my entire life. This is because it has positively impacted my teaching, my reading and my writing and vastly expanded my publishing.