News

Glyphosate back on the table as Govt. bows to pressure

The government of Sri Lanka, one of the first to ban glyphosate, then used indiscriminately as a weedicide in the agriculture sector, is now pondering a lifting of the ban.

Bowing to pressure from the tea industry, which has suffered losses worth billions of rupees in foreign exchange, the government has appointed a committee to review the ban – the committee is, however, headed by an MP who is actively lobbying against the lifting of the ban, Ven. Athureliye Ratharana.

The thera is an advocate of the movement “Wasa wisa nathi ratak” (A country free of toxic substances), that supports a promise made by President Maithripala Sirisena to ensure chemical-free farming within the first three years of his office.

The thera is an advocate of the movement “Wasa wisa nathi ratak” (A country free of toxic substances), that supports a promise made by President Maithripala Sirisena to ensure chemical-free farming within the first three years of his office.

In the three years since the ban was instituted, the government has not been able to come up with an effective alternative to glyphosate.

The tea industry, represented by Regional Plantation Companies, said it was being misrepresented as being the force pressuring the government to re-introduce glyphosate.

“No,” said Kelani Valley Plantation Chairman Roshan Rajadurai. “We are only asking for a suitable chemical as an efficient weedicide – an alternative to the banned chemical.”

He argued, nevertheless, that glyphosate had been very cost-effective and less harmful in the estate sector. “To our knowledge we do not have a single case where glyphosate has been the causative agent of kidney diseases,” he said.

With no alternative weedkiller the plantations are plagued with weeds, bringing down production. Thousands of acres of tea plantation have to be weeded manually and this has become a costly exercise for the industry. Scarcity of labour in the plantations has compounded the problem.

Ceylon Planters’ Association Secretary-General Malcolm Dias said that with no alternative to glyphosate couch grass was growing wild among tea bushes. “This has deep underground stems and spreads quickly, making it difficult to remove manually,” he said.

Another problem faced by the industry is that manual weeding disturbs the top soil on plantations, causing erosion and the subsequent carrying away of nutrients and minerals from the soil. This reduces the soil’s fertility, leading to a downturn in production.

The abundance of weeds has also provided a habitat for animals and insects, bringing down efficiency levels of plantation workers, who already work in trying circumstances in the biting cold.

Mr. Rajadurai recalled that the government in 2002, at a time when suicide rates were spiralling, had banned the weedicide, Gramoxone. Disillusioned farmers whose crops had failed and impulsive youth faced with life’s difficulties had found the chemical to be a handy means of bringing an end to their lives.

“After the ban on glyphosate, we have been using a mixture of chemicals to fight weeds and have no control over the MCPA (Methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid) levels that determine the maximum residue index (MRI) levels in a product,” he said.

Mr. Rajadurai said tea-importing countries were “exacting” and demanded that tea have low MCPA levels – as low as .001 as in the case of Japan. “This is difficult,” he said.

The risk of a backlash to MCPA in Sri Lanka tea shipments has prompted the industry to volunteer to have MCPA levels tested prior to export. Since January 2018, the number of companies volunteering for tests has increased.

Mr. Rajadurai maintained that up to now there has been no evidence that glyphosate contained a chemical linked to kidney disease. “It is used sparingly – around 1 per cent solution twice a year, and MRI levels are low,” he said.

Agriculture Department Director-General W.M.W. Wijekoon said when banning a product as widely used as glyphosate due consideration should have been given to both sides since, with no weedicide available, farmers are suffering. “Perennial weeds cannot be controlled manually. We should weigh the pros and cons before banning. It should not have been banned at all,” he said.

Using other chemicals, Dr. Wijekoon said, involves abundant use of water in fields, which was not possible at a time when the availability of water for agriculture was diminishing and was forecast to become scarcer in the future.

He said if there was an element of doubt about risks posed by glyphosate controls could have been imposed, with use restricted. Instead, Dr. Wijekoon said, the institution of the ban had increased the cost of cultivation because of weeding had to be carried out manually. Consumers would not be able to pay the consequent high price for paddy, which would prompt the government to import rice. “Farmers, not being able to compete with international markets, will abandon farming and rice production in this country will go down,” the Agriculture Department Director-General said.

“Most food items are imported from India and they have not banned glyphosate in that country,” Dr. Wijekoon pointed out.

He said any chemical used profusely was harmful and his department urged farmers to use agro-chemicals sparingly. “We ask them to use chemicals only when necessary. Use glyphosate only when necessary, not for all purposes. We want to carry this message into all farming areas in the country,” he said.

In 2015, when the ban on glyphosate was imposed, the department opposed the countrywide ban and recommended a ban only in provinces that had reported kidney disease. High rates of kidney disease (chronic kidney disease of unknown causes – CKDu) are being found among farmers in arid and tropical regions of the world, including in parts of Sri Lanka, where pesticides and weedicides are widely used. No definitive causal link has yet been established.

In 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO), together with the Presidential Task Force for CKDu Prevention, issued a communique stating there was no evidence to link glyphosate with CKDu. The ban on glyphosate had been imposed the previous year. At the time, stakeholders in the tea industry had expressed displeasure, saying they had not been consulted.

Rajarata University senior lecturer Dr. Channa Jayasumana, who is carrying out extensive research on CKDu, insists the ban should not be lifted. He said there was fresh evidence that the weedicide contributed to kidney disease in farming communities.

He said researchers have coined a more appropriate term – Chronic Interstitial Nephritis in Agricultural Communities (CINAC) – for the illnesses found to be common among young men and women in tropical climates exposed to toxic agro-chemicals through work or by ingestion of contaminated food and water or by inhalation.

However, the causes (aetiology) of CINAC are also not known. The disease is caused by any of several factors and is characterised by low or absent proteinuria (proteins detected in urine)and small kidneys with irregular contours in the latter stages of the illness.

Among the two hypotheses attributed as contributory causes are toxic exposure in agricultural communities and the recurring exposure to heat stress with episodes of dehydration. The absence of the disease in northern Sri Lanka, where heat stress is high, is explained by the minimum use of agro-chemicals in farming there. CKDu is prevalent in the North Central Province.

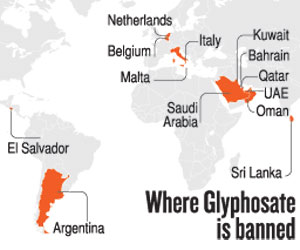

“There is sufficient evidence that the chemicals in the weedicide used is contributing to the disease. But we need to do more research to find the link to glyphosate,” Dr. Jayasumana said. Glyphosate is banned in only a few countries such as Malta, The Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Sri Lanka and six Middle Eastern countries including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

The European Union is considering a ban but with no near substitute it had postponed the decision and renewed the licence for glyphosate for two years in November 2017. Dr. Jayasumana said there was no evidence that supported the lifting of the ban in Sri Lanka and latest research on glyphosate showed that a chemical in glyphosate induced Parkinson’s Disease and was harmful to pregnant mothers who became exposed to the chemical.

“We need more research to prove it is safe. Until such time the ban should not be lifted,” Dr. Jayasumana said.