A duty to remember

“Not only had the Nazis killed all my family, destroyed my childhood, deprived me of my country, home and possessions and severed my roots – but they had also robbed me of my language. Because, although one can learn a new language, or many new languages, no language can really replace the mother-tongue.”

At the age of 13, Anne Ranasinghe, born Anneliese Katz, crossed the German border to Holland alone by train, heading for England as a child refugee. Not only did she leave behind her parents, whom she was never to meet again and whose fate even much later she could barely get to know about in enough detail, but she carried with her remembrances of scenes of horror which that time she was probably unable to understand as being the premises of Hitler’s mass extermination policy directed at the Jews, her community.

At the age of 13, Anne Ranasinghe, born Anneliese Katz, crossed the German border to Holland alone by train, heading for England as a child refugee. Not only did she leave behind her parents, whom she was never to meet again and whose fate even much later she could barely get to know about in enough detail, but she carried with her remembrances of scenes of horror which that time she was probably unable to understand as being the premises of Hitler’s mass extermination policy directed at the Jews, her community.

For Anne, it all started in August 1934 – one and half years after Hitler seized power in Germany, when she was nine. With the resilience of the child that she was, Anne stepped with a growing feeling of awe into what was to become the German nightmare of the 20th century. During that summer of 1934, the children of the youth camp which Anne participated in took a serious bashing for sheer racism – for their being German-speaking Jews in self-proclaimed ‘Aryan’ Germany: “Few of the children who were with me that morning survived the reign of terror that was about to be unleashed. Many would die under the most horrible circumstances.”

While the readers already know the ‘end of the story’, i.e. Hitler’s terrifying enterprise, Anne’s narration renders the growing alarm pervading the psyche of the Jewish citizens little by little deprived of all their rights: “True is the fact that no one really knew what Hitler was capable of.”

The annexation of Austria, then the invasion of Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Holland, France, and other North and East European countries are interwoven in Anne’s narrative with the events which affected the Katz family and which alarmed Anne beyond childhood’s disbelief. Anne saw first-hand “a positive orgy of sadism and horror. Large numbers of Jewish men and women were collected, then forced to scrub streets and clean gutters on their hands and knees.”

The culmination for Anne was the ominously infamous Night of Broken Glass on November 9, 1938, the largest pogrom unleashing the mass extermination of the Jews in Germany and Europe. In a span of less than three months Anne would see her family members disappearing and would follow her parents’ instructions to migrate immediately to England. “As for me, I went to bed on the night of November 9, the same way as usual.” Anne’s days in Germany and with the German language were numbered: the next day early morning the phone would ring – and news would follow: the burning of their city synagogue; the arrest of her father and his being deported to the concentration camp at Dachau; the sudden disappearing of her father’s complete family in the village side…

“I wandered round the house with a strange feeling in the pit of my stomach,” Anne recalls. In her narrative Anne tries to relate the dramatic incidents which she experienced, with the now known political evolution of Germany before and during WWII. For example, she tries to trace the earliest references to concentration camps – back to the very year 1934.

She witnessed the incomprehensible disappearance of her relatives, but also the erasing of the Jewish places of identity such as the synagogues, the Jewish children’s centres and schools, and beyond all this, beyond all sorts of denials of the Jewish identity which were until that time part of the German identity, she retrospectively understood “the dramatic effect on the cultural life of fascist Germany, a culture that was rapidly being destroyed, and a language that was ultimately also ruined.”

Anne as a child faced extermination – and survived. Frequently people say to me: “Why don’t you forget all those horrible things, why do you keep dwelling on the past, writing about it? Thinking about it? The past is over, done with.” Is it? A few of us have miraculously survived. Surely on us devolves a duty? – To me the millions who died are not just names on a piece of paper or carved in stone on some memorial: among them are people I loved, who shared my early life, who laughed and played and learnt with me. People who taught me and guided me, whom I admired. My parents.”

Anne was in England; her parents disappeared. It took her years to try to collect a little data about them: what happened after her departure by train for Holland, where were they displaced to, and when they probably died. “I had arrived in England in January 1939, and what happened to my parents after I left Germany I have only been able to reconstruct partially and much later.”

Memories of childhood: Anne, aged 13, seen second from left

Five rather cryptic postcards signed by her mother and addressed to the only aunt who survived in Germany allowed Anne to locate her parents in the ghetto of Lodz in Poland between November 1941 and June 1944 – then the extermination camp at Auschwitz where they died. “The miracle is that they survived so long under such dreadful conditions, the tragedy is that they perished so near to the end of the existence of the ghetto and the war.” They left Lodz for Chelmno in “what was probably one of the last ‘actions’ to take place before the Russians overran the ghetto.”

Anne’s narrative style is remarkable for its ability to render the impressions and feelings of the child that she was at the time: “One morning as I was dressing for school I was told to collect my visa from the British Consulate in Cologne, and then to visit my grandparents before coming home. To a child these things do not appear so tragic, the road of life stretches endlessly ahead. But for my grandparents, who realized they might never see me again, it was an overwhelming tragedy. In the evening we packed my bag.”

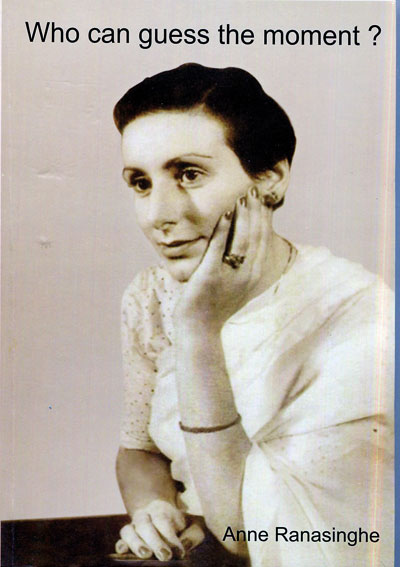

In 2014 and 2015 respectively, Anne Ranasinghe, now 90, published a new compilation of her previous writings on the subject, narratives as well as poems: Snow (334 pages), and Who can guess the moment?( 220 pages). These are testimonies for the sake of the duty to remember. “How can I accept the fact of my parents’ brutal and meaningless murder, smile politely and say: ‘All right. Let bygones be bygones?’ Never. Some of us must continue to remind the world that such an unbelievable crime happened: nothing will ever remove the shame of it, nor the tragedy.”