Where has the Man in Sarong gone?

S o when was the last time we saw a Man in a Sarong? Come to think of it, not too recently. He seems to have stepped off the map. These days, you would have to go out into the country to see the typical Sri Lankan male in typical indigenous male

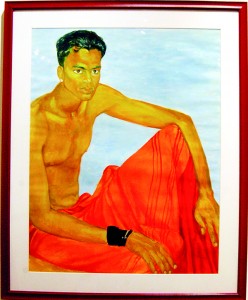

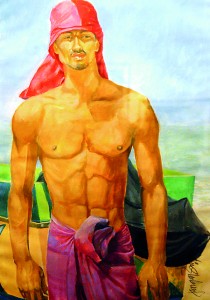

Celebrating the Sri Lankan male: Two of Beven’s paintings at the recent exhibition (above, and below right)

attire.

Till late into the Seventies, and even long after, the sarong was ubiquitous in the streets of Colombo. You saw it on the road, still or in motion. You saw it by the wayside and in boutiques and tea houses. But you do not see it much these days. Over the years the sarong has been gradually replaced by Western garb in the less dignified shape of trousers, denims, shorts, and funky knee-length garments. To claim that this trend is for the better is moot. There are those who will contend that the sarong is superior, aesthetically speaking, to the trouser as male dress. This difference is easily ascertained.

Hang on a clothesline a pair of trousers and a sarong. Which looks the more respectable? The sarong, of course. To our eye. Or imagine a catwalk at a male fashion show. Here come two athletic young men, one in a pair of black trousers, the other in a patterned sarong. Who catches the eye and excites admiration? The man in the sarong, of course. Sartorially speaking, the man in

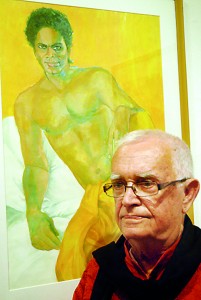

George Bevan. Pix by Nilan Maligaspe

sarong is by far the more elegant, the more becomingly dressed. You sense the difference the moment you walk into a venue where saronged gentlemen move about in the company of trousered and suited men, as is the case in certain upmarket hospitality industry venues in this country.

Juxtapose the sarong and the trouser for a deeper assessment.

For balance, the man in sarong and the man in trousers stand legs slightly apart. You are embarrassed and aware of the nether half of the one, but not of the other. The single-piece sarong is concealing and modest, and holds great charm in its simplicity. It is also subtle, sensuous, sinuous, shapely. The bifurcated trousers are crude compared. The sarong has mystery and poetry. Trousers have none.

David Paynter

Trousers were “those unmentionables” in Victorian England, Mr. Wiji Weerasinghe, English Literature teacher at Royal College, informed us, in a classroom diversion from “Pride and Prejudice” four decades ago.

Oh, come to think of it, we did see a sarong the other day. It stood out because we hadn’t seen one in a while. And it was in an upmarket setting. The tall young man who opened the door of the boutique hotel was sheathed in silver, from collared neck to hidden feet. He had on a white-and-silver threaded jacket and a glittering silvery sarong, artistically streaked with black lines. He looked magnificent – far smarter than the staff in black longs and white shirt on duty inside.

But that is the sarong worn as smart dress. What of the sarong as everyday wear? Where are the saronged men who were once so much a part of the town and cityscape? They were integral to the social and street-level scene up to 20 years ago.

Naked from the waist up, sarongs casually secured around slim waists, these men pulled rickshaws, carried panniers on their shoulders and fruit baskets on their heads, sold fish on bicycles, picked  coconuts, laboured at construction sites, polished brass, swept verandas, tended gardens, sat on boundary walls, lounged at front gates, and chewed and spat betel. The sun glowed on their brown skins, which went from tea to cocoa to coffee to bitter chocolate in hue. These topless men embodied in a beautifully unselfconscious way the beauty that is the Sri Lankan male. Sadly, this indigenous, graceful male has gone missing.

coconuts, laboured at construction sites, polished brass, swept verandas, tended gardens, sat on boundary walls, lounged at front gates, and chewed and spat betel. The sun glowed on their brown skins, which went from tea to cocoa to coffee to bitter chocolate in hue. These topless men embodied in a beautifully unselfconscious way the beauty that is the Sri Lankan male. Sadly, this indigenous, graceful male has gone missing.

We pass building sites daily. On these sites are workers who wear industrial safety helmets, shirts and trousers. Fifteen, twenty years ago, they would have been stripped to the waist and wearing shorts or tucked-up sarongs.

These thoughts on the sarong were set in motion recently by an exhibition of paintings by the Sri Lanka-born, London-based artist George Beven. The show might have been more aptly titled “Men In Sarong”, instead of the given generic title, “Heritage.” Of the many artworks on display, the majority were studies of men – Sri Lankan and Indian – and most of the men were bare-topped and in sarong. As with any George Beven event, the naked and half-naked men sell out first, even before the exhibition officially opens. The gallery invitation card was printed with a gouache portrait of a good-looking, bare-chested man in a blue sarong.

Sri Lankans – also Indians and other subcontinental English-speakers – say “bare-bodied” when they mean “bare-topped”. To the Westerner, bare-bodied is the equivalent of stark naked. Mr. Beven’s work embraces both bare-topped and “bare-bodied” men.

Beven, who grew up in the seaside town of Negombo, is in his element painting men, and especially the Asian male. His men are slim, lean, lissome, sinewy. Many are fishermen. The delicately muscled torsos are formed not in gyms but out in the gritty, grainy, perilous world of the sea. Muscles are formed by manning primitive fishing vessels and hauling in heavy, heaving nets. Skins are coloured and textured by extremes of sun, wind and rain.

In and out of sarong, Beven’s men are rendered lovingly and tenderly. Light and shadow play delicately on the contours. The artist is masterly in his lighting effects. In an effervescent seascape, sunlight explodes like champagne along the curve of a breaking wave and gleams on the backs of three young men splashing in the water. Men in their element.

In 1977, according to Neville Weereratne’s book “George Beven – A Life in Art”, Beven was invited to contribute to an art exhibition in London dedicated to the male nude, and two monotone works by Beven were hung in the distinguished company of artists like David Hockney and R. B. Kitaj. The following year, the paintings were reproduced in an artbook, “The Male Nude – A Modern View”, produced by Edward Lucie-Smith and Francois de Louville.

Beven’s men can also be surpassingly expressive. They have handsome, deceptively disinterested eyes. At least half a dozen of the men at this show held us with their gaze. (In the palatial Galle Fort residence of art collector Stephen LaBrooy hangs a George Beven study of an Indian gentleman in Indian dress; the face has to be one of the handsomest of any male we have seen in an artwork. The portrait invariably stops visitors in their tracks, according to the owner of the painting.)

The spectacle of the naked and half-naked dark-skinned male stands tall in a great deal of Sri Lankan art and photography.

George Beven learnt his craft under the Ceylon-born artist David Paynter (1900-75), whose own work is richly populated with draped and undraped men, as demonstrated in artist-writer Albert Dharmasiri’s two books on Paynter.

Paynter painted indigenous men with an uncommonly sensitive hand. His men are indigenous even when the setting is apparently not, as in the religious murals in the chapels of Trinity College, Kandy, and S. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia. The faces and bare-chested figures are ethnically of this country. See his Crucified Christ, flanked by the Two Thieves.

It was a revelation to see a true copy (in a private Colombo collection) of Paynter’s “L’apres-midi” (“The afternoon”), a study of two naked boys (who could be the same boy looking at himself posed front and back) seated on mats inside a bamboo grove. A true copy matches the original in size and colour palette. “L’apres-midi” as reproduced in Dharmasiri’s book had not prepared us for the impact of the true copy. But, then, is this not true of all reproduced art? (The original “L’apres-midi” hangs in the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, England.)

We were seven years old when we had our first glimpse of near-naked David Paynter men. There was an illustration of farmers in a paddy field in our first Sinhala reader, H. D. Sugathapala’s textbook for Royal Primary School pupils. The limber, long-limbed, mud-brown men left an impression.

George Beven and David Paynter are artists whose artistry flowers exotically when a susceptibility to male beauty is touched. This is also true of the work of photographer Lionel Wendt (1900-44). Some of Wendt’s most expressive photographs, most of them unpublished and curtained off in private collections, are of the nude and nearly nude Sri Lankan male, in classic black and white.

Indigenous male beauty caught the eye of another great artist in black-and-white, the Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-79). The pioneer portraitist, who photographed celebrities like the poets Tennyson and Robert Browning, came to Ceylon in 1871 and spent her last years on a tea estate in Bogawantalawa. Cameron recorded her impression of a bare-topped Ceylon male not in a photograph but in a letter sent home, in which she remarks on her gardener’s physique and “the beauty of his back.”

Like Julia Margaret Cameron, countless feudal-class ladies and gentlemen, colonial and native, have over the decades admired from the verandahs and recesses of their manors and walauwes the beauty of their half-naked vassals at work.

We should be grateful to artists like Wendt, Paynter and Beven, whose body of work preserves and reminds us of an aspect of communal beauty special to this country.

(Paintings by George Beven may be viewed on request at Gallery 706, Barefoot, Galle Road, Colombo 3; the book “George Beven – A Life in Art”, by Neville Weereratne, is available at the Barefoot Bookshop.)

comments powered by Disqus