Sunday Times 2

Sri Lanka: An Island lost in the Indian Ocean?

View(s):By Dinesh D. Dodamgoda

A few recent developments in Sri Lanka’s foreign relations imply that there is something flawed in handling the country’s external affairs.

The US’s resolution against Sri Lanka at the United Nation’s Human Rights Council, the campaign to shift the Commonwealth Summit venue from Sri Lanka, the recent hiccups in Sri Lanka’s ties with India and the US, the IMF’s refusal to lend US$ 1 billion to Sri Lanka and China’s reluctance to give a loan of US$ 500 million to buy petroleum products by Sri Lanka were some of the issues that indicated a few bumps that Sri Lanka experienced in its relations with international players.

It is evident that all these negative trends emerged not as a result of a single linear issue, but as a result of several issues that created vexatious problems for strategists. Amongst these issues, the last phase of the war against the LTTE has become the most pressing issue.

The war against the LTTE warranted international assistance and cooperation politically and militarily. In terms of political support, the West, the East and our neighbour India had agreed that LTTE terrorism should be defeated and a political solution to Sri Lanka’s ethnic problem be found. When reference to military support, some countries provided soft assistance while others provided hardware ranging from firearms to multi-barrel rockets.

Nonetheless, during the war, allegations against the Sri Lankan Government about non-compliance with international laws had altered the shape of the international political and military support to Sri Lanka.

Countries that uphold human rights and humanitarian laws started adopting a restricted approach in providing offensive military hardware to Sri Lanka, whilst countries that have relatively low respect for such civil values, started playing a principal role in providing offensive military hardware. Later countries, like Pakistan and China played a decisive role in not only providing arms and ammunition but offering credit as well. As a result of such assistance, especially from China, new dynamics in Sri Lanka’s foreign relations emerged with Sri Lanka realigning its alliances as China competes with the US and the West for world supremacy and power.

Grand strategic implications

The grand strategic implication of this ideational shift in Sri Lanka’s foreign relations allowed China to secure Sri Lanka’s cooperation for its Indian Ocean strategy, widely known as the “String of Pearls.” The US Army Strategic Studies Institute describes it in these words: “the strategy is understood as aiming at encountering American maritime power along the sea lines of communications (SLOC) and connecting China to vital energy resources in Africa and the Middle East”.

There are several “pearls” in the “String of Pearls” beginning from the coast of China in the mainland and going through the littorals of the South China Sea to the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf across the Indian Ocean: A Hainan Island’s upgraded military facility, a Woody Island airstrip, container shipping facility in Chittagong, Bangladesh, a deep water port in Sittwe, Myanmar, a fuelling station in Hambantota, Sri Lanka and a navy base in Gwadar, Pakistan. As observed, all these pearls are to ensure an uninterrupted flow of energy supplies to China, especially oil, as China’s oil consumption is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.8 per cent in the next 10 years. Roughly 40 per cent of the new world’s oil demand is attributed to China’s rising energy needs, and over 70 per cent of China’s oil imports come from Africa and the Middle East via sea. Hence, it is a top strategic priority to secure China’s sea lines of communication (SLOC) from the Middle East and Africa, to China, across the India Ocean and South China Sea.

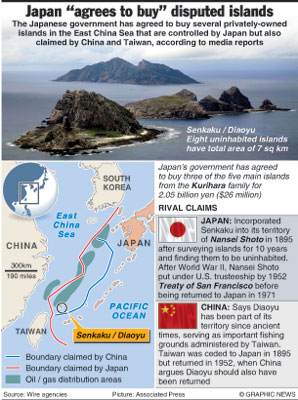

China’s quest for superpower status requires its leaders to meet three main strategic demands: regime survival, territorial integrity, and domestic stability. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will not tolerate any political dissent that would threaten the regime’s survival. Furthermore, China has made progress with respect to territorial integrity as the country stabilised and demilitarised many issues related to land borders in North and Central Asia although issues such as the unification with Taiwan and the dispute with Japan over Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands remain unresolved. Moreover, the issue of domestic stability is dealt by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) with the use of persuasive and coercive mechanisms. However, it is important to note that all these three main strategic demands — regime survival, territorial integrity, and domestic stability — are necessarily linked to the economy. To sustain economic growth, China must rely on external sources of energy and raw material, where the sea lines of communication have become China’s utmost priority.

The US and the “String of Pearls”

China’s strategy aimed at securing its sea lines of communication had an impact that went beyond the region. In the fall of 2011, the Obama administration issued a series of announcements indicating the United States’ intention to shift the country’s main strategic focus to the Asia-Pacific region and this policy was then known as “Pivot to the Pacific”. As the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) noted, the United States’ Asia “pivot” has aroused Chinese anxiety and heightened regional worries about intensified US-China strategic competition. The situation has somewhat polarised the region with both China and the US trying to indentify allies in the Asia and Pacific region. The US found India and Japan as its explicit allies while China found Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Cambodia and Vietnam as its implicit or explicit allies.

Amongst the above mentioned allies, India’s engagement with the US is influenced by India’s drive to become an Indian Ocean power. In terms of Indian strategic calculations, maintaining strategic cooperation with the U.S. is of paramount importance as the US will remain as the world’s superpower for the next few decades. Furthermore, India too, has growing needs for external energy. Around 70 per cent of its oil requirement is met by Persian Gulf supplies via sea. This requires India to maintain sea lines of communication. Therefore, India, the country that supported the Soviet Union against the U.S. during the Cold War era, has decided to align itself with the US in the hope that such an alliance is in the best interests of India in view of the power struggle in the Indian Ocean.

However, it is interesting to note that as the US would not allow any Asian power to rise to the level of a superpower in the Asia-Pacific and the Indian Ocean region, China’s strategic options will tend to be shaped by ‘reality’ rather than China’s ‘normative’ strategic objectives. This is to say that in the future China will call for strategic cooperation with the US and India, instead of competing with them for superpower or regional power status. This strategic option would facilitate China’s three main strategic goals — regime survival, territorial integrity, and domestic stability. Such a scenario poses complex questions for strategists, especially in countries like Sri Lanka, which may depend on China’s leadership. Hence, it is worth checking available strategic options for Sri Lanka.

Strategic options available for Sri Lanka

In developing a regional strategy for Sri Lanka, there are a few key issues that need attention.

They are:

- The U.S. will remain as the world’s superpower for at least another decade or two.

- India is Sri Lanka’s big brother which has a higher influence than China; hence, any strategic move should not antagonise India.

- Sri Lanka’s China policy has to be worked out in the context of a possible strategic cooperation between the US and China in the future.

- China would not go any extra mile beyond the strategic objectives in assisting Sri Lanka as was evident in its refusal to give Sri Lanka a US$ 500 million loan to buy petroleum products.

- No single superpower will succeed in the Indian Ocean region and therefore, India and China both will remain as superpowers in the region for the conceivable future.

- Sri Lanka should aim at building neutral strategic cooperation with the US, India and China on the basis of Sri Lanka’s national interest.

However, as a final thought it is worth mentioning that building strategic cooperation with the US, India and China on the basis of Sri Lanka’s national interest, makes the subject of International Relations an art rather than ‘science’. So, we need more strategists who know the craft rather than hooligans who depend on rhetoric in formulating countries international affairs strategy.

*Dinesh D. Dodamgoda, a lawyer, has an a M.Sc. degree from the British Royal Military College of Science, Shrivenham (Cranfield University) on Defence Management and Global Security. He was also an MP from 1995-2000.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus