Sunday Times 2

The saga of Assange: What the International law says

The historical dimensions of the “Triangular episode” of the Assange Saga are well known. Among the various alleged sins committed by Julian Assange, an Australian citizen, he is accused of a particularly heinous sin which has resulted in this “triangular paradigm” of a diplomatic battle involving three nation states.

He is alleged to have committed a sex offence in Sweden for which the Government of Sweden has issued an international arrest warrant through Interpol. The Government of Ecuador has provided him with asylum and Assange now remains in self-imposed incarceration inside the rather cramped premises of the Ecuadorian Embassy in the United Kingdom. And thirdly, the UK Government has placed a cordon around the Ecuadorean embassy to prevent Assange from escaping from those premises, and possibly reaching Ecuador for his own personal safety and freedom.

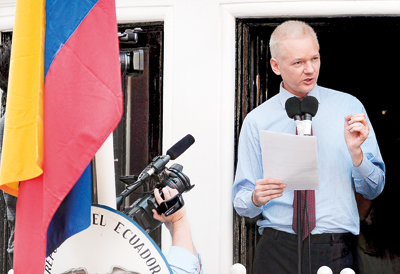

A file photo taken on August 19, 2012 shows Wikileaks founder Julian Assange addressing the media and his supporters from the balcony of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. AFP

The State parties to this triangular episode are: Sweden, Ecuador and the United Kingdom. Assange’s Australian citizenship remains only as a distant observer to this conflict.

There are other sins too that Assange is alleged to have committed, such as leaking through WikiLeaks the inner secrets of the United States for which, in that country’s law may earn him a sentence of a life imprisonment or even death. That matter, however, is not directly relevant at the present moment, but it will become directly relevant if and when Assange is sent back to Sweden. The US may then seek his extradition from the Swedish Government. That is, at present, a peripheral issue which I do not intend to deal with here.

The three issues

There are, therefore, three matters that require some consideration. First, is the Ecuadorian embassy in breach of the Diplomatic Law under the Vienna Convention, if it were harbouring a “Fugitive from Justice”? Second, has the “Receiving State”, the UK, under the Convention or under the Diplomatic Law arising from the Convention, a power to enter with force, the premises of the Ecuadorian embassy to seize Assange, in execution of the International warrant issued by Sweden, to arrest and extradite him. Lastly, is Assange a “fugitive from justice” from Sweden or the UK?

First, the issue of harbouring a fugitive from justice in the diplomatic premises of the sending state has raised many complex problems. It raises the issue of giving asylum to a fugitive from justice and the concomitant rights of the receiving state to cause a forcible entry into the premises to seize that fugitive. An additional problem in the Assange case is that Assange is not a fugitive from justice from the receiving state but from a third State which is neither in the present fact situation is a sending state nor the receiving state. He is alleged to be a “fugitive from justice” from a “Friendly State” Sweden.

A Third State.

The available case law deals with diplomatic premises of sending states harbouring “fugitives from Justice” from the receiving states and not from “Friendly States”. The classic case in point is that of Dr. Sun Yat Sen (1896), who was a refugee from China, living in London. He was regarded as a “fugitive from Justice” under the Chinese Law. The Chinese Legation in London had Dr. Sun kidnapped and was held as a hostage at its Diplomatic premises. Upon an application made to the U.K. courts to have a writ of habeas corpus issued against the Chief of Mission, the English court held that the detention without the avowed consent of Dr. Sun was unlawful under the English Law and therefore it constituted a breach of diplomatic privilege. The court thereupon requested that there should be a diplomatic dialogue on this matter and the proper course which the Chief of the Mission should take was to release Dr. Sun. Dr. Sun was thereupon released. As later events records, Dr. Sun subsequently became the President of the Republic of China. In diplomatic parlance China, at the time, could be characterised as a “Friendly State” of the UK as Sweden is at the present day. The situation is different where the person given asylum is a person who is a “fugitive from Justice” of the receiving State.

In 1966, a Chinese Engineer was visiting The Hague to attend a conference of Welding Engineers. At a particular point of time, during his visit, he was found in a severely wounded condition, lying on the road, outside the home in which he was temporarily staying. The Netherlands authorities had him removed to a hospital. While the wounded person was lying on his bed, a few of his colleagues who had also come to attend the same meeting removed him and carried him to the Chinese Mission. While being held in the Mission, the wounded person died. Death having occurred as result of an act committed within the jurisdiction of the receiving state, the dead man’s colleagues were important, as witnesses, from whose evidence the prosecutor could determine whether there had or had not been a commission of a crime. The Netherlands authorities for that reason required the deceased person’s colleagues to be made available to the Netherland’s prosecutor for questioning.

The Chinese Chief of Mission in the Netherlands refused access to the Diplomatic Mission to question them. The receiving state, The Netherlands, not only did declare the Chief of Mission a persona non grata but also had the premises in which the mission was, surrounded, to prevent the escape of those persons whom the receiving state desired to question. This siege lasted nearly five months where upon the Chinese government agreed to permit the witnesses to be questioned by the public prosecutor within the premises.

This is a fact situation which raised questions regarding the commission of a criminal offence alleged to have been committed within the jurisdiction of a receiving state. In this aspect, the situation differs from that of Assange’s. Assange had not committed any offence within the jurisdiction of the receiving state. Therefore there is no state interest in the receiving state (UK) to pursue.

The available case law deals with wrongs committed within a receiving state and not those committed within a “Friendly State”.

The case of Dr. Sun concerned a “fugitive from justice” from a “Friendly State” but he was granted asylum and his forced removal and incarceration within the Chinese Legation constituted a wrong under the law of the receiving state, which amounted to kidnapping. In that aspect it is similar to the 1966 matter from the Netherlands mentioned above. Therefore the issue of the writ of habeas corpus in the case of Dr. Sun was justifiable.

Second , the principle of inviolability of diplomatic premises may be found in literature dating to a period before Grotius (1625). The principle requires the receiving Sovereign to refrain from applying its laws to such premises. Article 22 is quite explicit when it declares that:

“1. The premises of the mission shall be inviolable. The agents of the receiving State may not enter them, except with the consent of the Head of the Mission.

2. The receiving state is under a special duty to take all appropriate steps to protect the premises of the mission against any intrusion or damage and to prevent any disturbance of the peace of the mission or impairment of its dignity.

3. The premises of the mission, their furnishings and other property thereon and the means of transport of the mission shall be immune from search, requisition, attachment or execution”.

Paragraphs (1) and (3) places a duty upon the receiving state to abstain from exercising its rights which it may otherwise exercise with reference to persons and property found on its own territory. There is a clear exclusion of rights of a “receiving state” exercised from the embassy property of a “sending state”. To that extent the UK government is in breach of Diplomatic Law arising from the aforementioned Article 22 paragraph (3) if its executive arm were to search an Ecuadorean embassy vehicle in which Assange may be found travelling. Perhaps the situation may be different if Assange were a refugee from justice of the UK, the receiving State. The principle adopted by the Netherlands in 1966 in the matter of the Chinese Welding Engineers would then apply. But Assange did not fall into that category.

Paragraph (2) of Article 22, however, deals with a separate issue. That deals with the dignity of the “sending state” in the eyes of the inhabitants of the “receiving state” and of other diplomatic representatives in the receiving state.

This is equally important in maintaining, in the “receiving state”, the diplomatic status, the dignity, and respect of the “sending state”. Encircling the Ecuadorean Embassy in London, ostensibly to prevent Assange from escaping, amounts to publicising that the Ecuadorian embassy is harbouring a criminal, a fact which has yet to be decided. That quite clearly affects the dignity of the “sending state” which the “receiving sate” breaches, by breaching paragraph (2) of Article 22.

Third, the Swedish legal system, like most European legal systems, requires the appointment of a judge, who has been specially trained and qualified to provide a judicial cover to inquiries made to a crime. When a report of a crime is made, the police are required to request the appointment of “juge de instruction” or the “examining judge” under whose guidance and watchful eye, the Police enquiries into the crime are conducted. This requirement that Police enquires are conducted under the direction of a judge constituting an impartial body ensures that the Police enquiries are conducted according the procedural law of the land. This prevents the hiding of exculpatory evidence which may point to the innocence of the suspect person. Both evidence incriminatory and exculpatory are produced and are compiled into what is referred as a “Dossier”.

It is when that document is completed that the “examining Judge” makes the determination whether there is a suspect to be charged, and what offence should he be charged with. The “Dossier” , euphemistically saying, “presides over the trial” , and its contents, may be challenged by Counsel as the trial proceeds. There are some ill effects in this process but the important issue is that the decision to charge a person and what the nature of those charges would, be are made by an independent body – the “examining judge” – upon evidence gathered by the executive agencies of the State, the Police, acting under the guidance and supervision of an impartial judge. Until that stage is reached there is no single person who may be characterised as an accused and therefore a fugitive.

In Assange’s case that stage is several stages away and until that stage is reached he is not a “fugitive from Justice” but is a person required to be questioned by an “examining judge”. In the present situation a meeting for that purpose could be held in London, at the Ecuadorian embassy. In fact “Instructing judges” from European jurisdictions have travelled to other countries to interview those who are key witnesses to a crime. The Chief Magistrate from Madrid came to London to question Augusto Pinochet after which he filed for his extradition to Spain to stand trial.

Conclusions

Unless there is some other motive to get Assange to Sweden, an instructing judge could easily have gone to London to prepare the “Dossier”. That is my first conclusion.

My second conclusion is that now that Assange is in the protection of the Ecuadorean Government, the Interpol warrant should now be directed at the Ecuadorean government for the same reasons that justified the issue of the Interpol warrant to the UK Government. Interpol has the power to change the direction of its warrant towards the State in which the person for whose arrest is found. Under diplomatic law Assange is presently found on Ecuadorian territory and not upon UK territory. Therefore the State to which the warrant is issued is not the State in which Assange is found but a State that seeks to “Invade” (forcibly enter) a State in which Assange is found. Why therefore is the Interpol not requested to change the State to which the request of arrest is directed from the UK to Ecuador?

My third conclusion is that the case raises important points of International law and they need to be considered by the International Law Commission at a future date. The commission has not made a decision on “Diplomatic Asylum” and the Vienna Convention has no provision referring to it. The provision of Asylum to Julian Assange, by the Government of Ecuador does not bring him within the protection of the Vienna Convention. What Assange may seek is the protection to which the State of Ecuador is entitled under the Vienna Convention to give him, but not by way of “Diplomatic Asylum”. The latter under Diplomatic Law is very different from “Asylum” which the Government of Ecuador has given Assange.

The General Assembly Resolution 685 (VIII) which provided the mandate for the Commission to consider “diplomatic privileges and immunities”, expressly excluded any consideration of “diplomatic asylum”. It was considered a complex matter to be left for another day.The writer is a judge of the Court of Appeal

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus