Her life went round the same circle. She had an arranged marriage just like others of her ilk; she spent her holidays at her mother’s and her teenage children went to school. She lived a normal life in the eyes of others in Patna, a small town in India.

Until, a break appeared in this circle.

Author Sharmila Kantha in her book “The Break in the Circle” launched this week at the National Library Services auditorium depicts the life of protagonist Anuradha in Patna.

An accomplished author, Ms. Kantha has written several books, some for children. She is the wife of Indian High Commissioner in Sri Lanka Ashok. K. Kantha. Author Sharmila Kantha in her book “The Break in the Circle” launched this week at the National Library Services auditorium depicts the life of protagonist Anuradha in Patna.

An accomplished author, Ms. Kantha has written several books, some for children. She is the wife of Indian High Commissioner in Sri Lanka Ashok. K. Kantha.

The “circle” in the book represents the cycle of responsibilities and duties one undertakes while living in society. “Break”, on the other hand, is the change in Anuradha’s mindset that occurred due to her correspondence with a professor, who was settled in the US and was going to visit Patna. She begins to see her life from another person’s perspective and starts to question her own identity. The book focuses on the self-revelation and discovery of herself.

Amidst a gathering of prominent Sri Lankan authors and personalities, External Affairs Minister G.L. Peiris and Goolbai Gunasekera spoke about the book.

Prof. Peiris saw the story as a conflict between two ideas. “The story is based on two sets of ideas. One which is acceptable by society and the other that is unconventional and introspective. In other words, the story is a conflict between continuity and change or future versus past,” the minister said. Amidst a gathering of prominent Sri Lankan authors and personalities, External Affairs Minister G.L. Peiris and Goolbai Gunasekera spoke about the book.

Prof. Peiris saw the story as a conflict between two ideas. “The story is based on two sets of ideas. One which is acceptable by society and the other that is unconventional and introspective. In other words, the story is a conflict between continuity and change or future versus past,” the minister said.

A versatile author herself, Goolbai Gunasekera appreciated Sharmila’s delicate and sensitive portrayal of women in the book.

While depicting the life of Anuradha, there are also references to various norms and customs prevailing in society. Mrs. Kantha takes on some of them such as Indian society’s obsession for fair-skinned girls, the boy child, television serials and dowry.

The book also showcases the changes in the mindset of the younger generation and society’s resentment of them. One of Anuradha’s relatives wants to become a model and this decision is ridiculed by family and society alike. The integral concern for the family is what other people would say and how they would be able to find a bridegroom for her in the future.

Published by Vijitha Yapa Publications, “The Break in the Circle” is priced at Rs 800.

A rare portrayal of empathy

"A Clear Blue Sky", the title given to this collection of short stories and poems, is the title of the only Sri Lankan story in this remarkable volume, and is authored by Elmo Jayawardena (winner of the Gratiaen Award some years ago for his book "Sam's Story”).

Book facts

"A Clear Blue Sky" - Stories and Poems on Conflict and Hope by Elmo Jayawardena.

Published by Puffin |

Reviewer Richa Jha, writes: "A new collection that challenges young adults to think about violence and intolerance."

There follows an extract from Elmo's story about a young Tamil boy forcibly conscripted by the LTTE. "Nothing in the book captures these binary forces as movingly as Jayawardena's closing lines.

“Children today are already over-exposed to images of death, guns, war, intolerance and communal riots. Now young adult fiction in India is increasingly willing to talk about these issues without mincing words. “The stories in `A Clear Blue Sky.' give readers glimpses - some poignant, some funny, some cruel - into the human capacity for hating what is different."

I had the good fortune to read Elmo Jayawardena's story. He has created a character and a story that starkly convey how war destroys childhood and families and lives. Selva is rudely taken away from his uncomplicated and congenial environment in a little village where his parents and everyone else grew chillies.

The picture of "Little boys doing grown men's work and fighting and dying for something they knew nothing about," is poignantly and convincingly drawn.

This is a story that pierces the heart - no heroics, but a rare empathy for, and a keen perception of, the meaningless suffering that war often inflicts on innocent lives.

A.A.A.

E-Danda: Capturing the revolt of the 80s, a first in English literature

Mineka P. Wickramasingha’s first novel

E-Danda was launched recently. Addressing the gathering at the launch, Prof. D.C.R.A. Goonetilleke commented on the significance of the book to Sri Lanka.

Mineka P. Wickramasingha ( Mickey) is an adherent of the Yoga and Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo Ghose and The Mother of Pondicherry, South India, and took to serious writing as a part of his spiritual discipline. In 1995, he published a collection of stories titled The Playmate. E-Danda was launched recently. Addressing the gathering at the launch, Prof. D.C.R.A. Goonetilleke commented on the significance of the book to Sri Lanka.

Mineka P. Wickramasingha ( Mickey) is an adherent of the Yoga and Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo Ghose and The Mother of Pondicherry, South India, and took to serious writing as a part of his spiritual discipline. In 1995, he published a collection of stories titled The Playmate.

This volume won the State Literary Prize in the category of Short Stories. Mickey has thus already shown that he is a thinking and talented writer. Most Sri Lankan writers tend to write short poems and short stories because writing is for them a part-time vocation, understandably given that they could not live by the pen. Writing a novel requires steady application. Fortunately, Mickey has found the time to produce a novel, an achievement in itself. It has had a long period of gestation, not unexpectedly given his business commitments. However, this has proved fortunate in that it has imparted a depth to the thinking behind the novel.

The JVP insurgency of 1988-89 is the focus of the novel. It has been said of the earlier JVP insurrection of 1971 that it shook not only our complacency but our conscience. The later revolt too had a similar impact in some quarters and, probably, on Mickey himself.

The insurgency of 1971 spurred Sri Lankan writers to produce a number of remarkable creative works about it. Curiously, Raja Proctor’s novel Waiting for Surabiel had an anticipatory conclusion that another insurrection was a possibility. This played itself out in 1988-89.

There was a wide gulf between the JVP of 1971 which was considered idealistic, and the JVP of 1988-89 which was regarded as bloody. There was consequently a wide gulf between the attitudes in Sri Lanka towards the two insurgencies – sympathy, even admiration, in some quarters, in 1971; alienation, even horror, in 1988-89. Mickey is different in that, while he notes that the JVP in 1988-89 was bloody, nevertheless regards the rebels as still idealistic. Mickey is, probably, right in thinking that the insurgents were basically still idealistic though the means they employed were more tainted.

The title of Mickey’s novel, E-Danda, is significant. The e-danda is, at one level, real: it is the gateway to Kohomba Kanda, the village which is the main setting of the novel. It is also the unmistakable symbolic centre of the novel. Kalu, the rural youth who had made good in London, returns to the village, points to the e-danda and shouts: “This is what the insurgency is about.” (p.164) The narrator glosses:

The e-danda links together the present with a civilization two, three, four centuries back, or is it a relic of primitive origin that still exists in the modern world?

The novel has it that the e-danda is both. The traditional father tells Kalu: “Yes son, still the e-danda. It has been here from the time I came to this village and I hope it will remain till I die.” (p.138)

The educated rural youth like his son Pol, who form the backbone of the insurgency, want to end the stagnation which the e-danda represents for them, the status quo which grinds them down. The narrator is bold and forthright in his condemnation of the inequalities and iniquities of the present system and is unsparing in holding the politicians responsible for it.

E-Danda is, first and foremost, a political novel. It is also a novel with human interest. The insurgents are normal human beings who also have interests other than politics. The politics of the novel is interwoven with two love stories so that its appeal becomes wider.

Unlike the 1971 insurrection, the 1988-89 revolt did not result in much creative writing. E-Danda, in fact, is unique in that it is the only novel in English so far about this important period in our history whose currents are still with us.

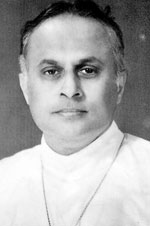

Amazingly relevant to our times, on matters ecclesiastical, social and political

Book facts

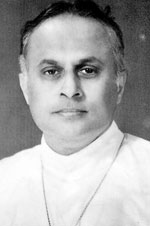

“Visionary Wisdom Of A People’s Bishop”- selected texts by Rt. Revd. C. Lakshman Wickremasinghe 1927 – 1983. Available at the EISD, 490/5, Havelock Rd., Colombo 5.

Price Rs. 700. |

It is with a sense of inadequacy for the task before me that I begin this assessment of a book that must surely shake up all who read it – as I have no doubt those who moved with him in his lifetime were shaken by the almost revolutionary thinking that characterized Bishop Lak (as he was affectionately called), on matters ecclesiastical, social and political.

The breadth of his concerns is evident at a glance at the headings of the different sections of this book which Marshal Fernando, Director of the Ecumenical Institute for Study and Dialogue, has so ably compiled: Church and Its Mission; Interfaith Relations; Church, Politics and Development; Social Justice; Asian Perspectives; Contemporaries; Ethnic Relations. Fittingly, these chapters are preceded by Bishop Lak’s Enthronement Sermon given when he formally took over as Bishop of Kurunegala in 1963, and conclude with his final Pastoral Address made 20 years later, prior to his death in 1983. The breadth of his concerns is evident at a glance at the headings of the different sections of this book which Marshal Fernando, Director of the Ecumenical Institute for Study and Dialogue, has so ably compiled: Church and Its Mission; Interfaith Relations; Church, Politics and Development; Social Justice; Asian Perspectives; Contemporaries; Ethnic Relations. Fittingly, these chapters are preceded by Bishop Lak’s Enthronement Sermon given when he formally took over as Bishop of Kurunegala in 1963, and conclude with his final Pastoral Address made 20 years later, prior to his death in 1983.

Reading a few paragraphs of that Enthronement Address made me sit up. After pointing to the increasing worldliness of our society today and stating that Christians are not immune to worldly temptation, the Bishop makes the startling statement that “many Christians improved their finances, rose in status and lived a second-hand kind of religion which turned to God only in trouble or in need.”

There is more (and worse) to come, but that sentence is sufficient to indicate that Bishop Lak’s view of pious church-people was not a comforting one. Coming to his last Pastoral Address, I would quote these words: “The arguments that have been stated so far point to one basic moral fact.

“It is that the massive retaliation, mainly by the Sinhalese against defenceless Tamils, in July 1983, cannot be justified on moral grounds.

“We must admit this and acknowledge our shame……….” The Bishop of Kurunegala was not one to mince his words and quite often they would displease the establishments of both church and state. From beginning to end, Bishop Lak’s central position is consistent. In order to be true followers of Christ, our lives cannot contradict the beliefs we profess. Jesus Christ was Love incarnate and He came to serve humankind, embracing in His love and compassion all the disadvantaged and down-trodden people of the earth.

So we cannot remain enclosed within church buildings, deaf to the oppression and injustices of the world outside church doors. The section of the book, dealing with Mission, Politics and Evangelism, contains a lecture he delivered in 1979 at an annual meeting of the Anglican Church Missionary Society. He challenges his hearers all the way, pointing out that popular evangelism has been content to “use Scriptural words communicating capitalist values and cultural attitudes alien to the enduring ethos of indigenous culture.”

It is clear that for Bishop Lak, religion HAD to concern itself with poverty and the denial of basic human rights, with social and political issues, with industrial conflict and non-violent demonstrations.

So it doesn’t come as a surprise when, in a Christmas message written in December 1980, he emphasises and highlights two aspects of the Christmas message, thus: (1) To care for the helpless and rejected in society and (2) To remove barriers of prejudice, injustice and indifference. He elaborates briefly on both.

Bishop Lak states boldly that “Christians have a special obligation to a group of people who are defenceless due to Government policy” and calls for active concern and support for the families of strikers who have been locked out from work for four months and to press for the restoration of their jobs to the said strikers. Not quite what many worshippers would have had in mind!

His next proposition is that Christians, especially, are challenged to bend their energies in the service of the ‘Prince of Peace’ by working “to remove the barriers of prejudice, injustice and indifference in the midst of Tamil-Sinhala conflicts.”

In an electrifying lecture he delivered in 1962 as Chaplain of the University of Ceylon, he states at the outset that thinking people, and especially university students, must resist the popular tendency to swallow wholesale the `fictitious words’ with which politicians often take in a gullible public – citing, among other fictions, a phrase that still sounds very familiar today – “the will of our patriotic common people.”

This whole lecture would bear repetition at the present time because of its compelling relevance to our situation today, 48 years later. As I read on, it’s the relevancy of so much that he has voiced or written, to life in our country as we know it today, that most impresses me.

Look at this extract from a letter in the Ceylon Churchman in December 1966 under the heading of `Development’. –

“The pace of development we require can only emerge if there is a spirit of patriotism both among our leaders and among the generality of our people, which accepts austerity instead of hankering after luxuries, hard work rather than laziness, a will to succeed instead of short-sighted defeatism, and a refusal to indulge in multiplying religious exercises and ceremonies to escape from the difficulties of daily life.”

It’s not surprising that Bishop Lak was a founder-member of the Civil Rights Movement (CRM), of which he later served as Chairman. His public-spiritedness was such that in his capacity of Bishop, he spoke out on many matters of public concern –echoes of which we welcome today in the voice of the present Bishop of Colombo, Rt. Rev. Duleep de Chickera, who is also not slow to respond to political issues that should engage us all.

In a letter in the ‘Ceylon Churchman’ (1967), Bishop Lak draws attention to the way in which parties that are in the Opposition at a given time and protest against what they see as wrongdoing on the part of the powers-that-be, change their tune when they in turn assume power and brazenly commit the very misdeeds for which they castigated the previous government. “Governments may change, but democratic principles remain the same, and these principles have a higher claim to our loyalty than party loyalties.

”Let us pray and work for the restoration of all lost civil liberties. Vigilance is the price of liberty.”

Then in a note written in December 1971, regarding the formation of the CRM, the Bishop says: “At present this movement is committed to work for the removal of existing restrictions on publications and public meetings, for the recovery of basic civil rights to persons taken into custody, dead or alive, and for the relief of those victimized and penurised as a result of the insurrection. It is essential that we all keep vigilant to ensure that temporary restrictions are not prolonged into indefinite deprivation of civilliberties.”

There are two very cogent letters written to President J.R. Jayewardene. In the first he strongly urges the President to withdraw the move to strip Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike of her civic rights. In no uncertain terms he makes it clear that this is a retrograde step which will undermine the whole fabric of democracy and of the “righteous society” (which JR had spoken of ushering in). The second letter, written in July 1980 in Bishop Lak’s capacity of Chairman, CRM, strongly deplores attacks on peaceful demonstrators by thugs against whom the police took no action.

“At a recent meeting our Movement discussed at some length the events of June 5th when a day of protest launched by several Opposition trade unions, and counter-protest called by pro-Government unions, culminated in injuries to several of the demonstrators, (for the most part from the Opposition side), and the tragic death of one of them……….”

Doesn’t that immediately bring to mind a similar occurrence of very recent times, (except that mercifully, nobody was killed)? The Bishop’s exhortation that “In such circumstances a special responsibility must lie on a government to ensure that law and order is maintained and in particular that opposition demonstrators are not attacked by government supporters.

“For supporters of a government in power often feel that they can flout the law with impunity, and some leaders may even encourage them to do so. Similarly, there are always some police officers who are reluctant to be firm with those they believe to enjoy political patronage.”

I have highlighted these words because they might well have been written in the present context, so apt are they for today. It is very tempting to end this inadequate review of a book that should be read by all who have an iota of concern for the present state of Sri Lanka, with a detailed reference to the final Pastoral Address to the Diocese of Kurunegala, given in 1983, a few months prior to his untimely death – a death which his close associates attribute to his increasing anguish and near-despair as he visited refugee camp after refugee camp housing the victims of the anti-Tamil riots of July ’83.

He had returned to the island after a sojourn abroad, determined to build bridges of friendship and understanding between the two majority communities and it seemed as if his dearest hopes had been smashed and trodden underfoot.

A perusal of that last Address should have a sobering effect on all but the hardest hearts. I will conclude, instead, with an excerpt from Bishop Lak’s lecture delivered at the Opening Session of the Asian Theological Conference held in 1979, because, once again, his words have a prophetic ring.

After recounting four very pertinent stories, Bishop Lak talks of “The need to struggle against feudal-capitalism and neo-colonialism in Sri Lanka and elsewhere in Asia. Capitalism with its emphasis on unjustifiable profits and unrestricted capital formation and enterprise, feudalism with its exploitative land-tenure and caste practices, and neo-colonialism with its exploitation of developing countries by affluent nations, are social systems that must be opposed and changed. They prevent the majority of our people from realizing their full humanity and basic human rights.

“The rich become relatively richer and the poor relatively poorer. The values of these social systems permeate religious institutions as well, and religion gets used to justify exploitative practices.”

Bishop Lakshman’s voice was always raised against unrighteousness of any kind. His life was a challenge to political and religious leaders and to all of us ordinary citizens to pay attention to what goes on in our midst and to take action against the things that could destroy us as a nation.

Was his a voice crying in the wilderness? It might seem so, judging by our situation today. The last section of this absorbing book contains some of the eloquent tributes paid to Bishop Wickremasinghe by a variety of people.

I have picked a pragmatic sentence from Fr. Paul Caspersz’s tribute, with which to end my review: “We who are destined still to watch the minutes of the night, have the task of keeping Lakshman’s light burning until the dawn breaks. Like him, we have to continue to analyze our human condition and strive relentlessly to keep it essentially and eminently humane.”

Anne Abayasekara |

Author Sharmila Kantha in her book “The Break in the Circle” launched this week at the National Library Services auditorium depicts the life of protagonist Anuradha in Patna.

An accomplished author, Ms. Kantha has written several books, some for children. She is the wife of Indian High Commissioner in Sri Lanka Ashok. K. Kantha.

Author Sharmila Kantha in her book “The Break in the Circle” launched this week at the National Library Services auditorium depicts the life of protagonist Anuradha in Patna.

An accomplished author, Ms. Kantha has written several books, some for children. She is the wife of Indian High Commissioner in Sri Lanka Ashok. K. Kantha.  Amidst a gathering of prominent Sri Lankan authors and personalities, External Affairs Minister G.L. Peiris and Goolbai Gunasekera spoke about the book.

Prof. Peiris saw the story as a conflict between two ideas. “The story is based on two sets of ideas. One which is acceptable by society and the other that is unconventional and introspective. In other words, the story is a conflict between continuity and change or future versus past,” the minister said.

Amidst a gathering of prominent Sri Lankan authors and personalities, External Affairs Minister G.L. Peiris and Goolbai Gunasekera spoke about the book.

Prof. Peiris saw the story as a conflict between two ideas. “The story is based on two sets of ideas. One which is acceptable by society and the other that is unconventional and introspective. In other words, the story is a conflict between continuity and change or future versus past,” the minister said. E-Danda was launched recently. Addressing the gathering at the launch, Prof. D.C.R.A. Goonetilleke commented on the significance of the book to Sri Lanka.

Mineka P. Wickramasingha ( Mickey) is an adherent of the Yoga and Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo Ghose and The Mother of Pondicherry, South India, and took to serious writing as a part of his spiritual discipline. In 1995, he published a collection of stories titled The Playmate.

E-Danda was launched recently. Addressing the gathering at the launch, Prof. D.C.R.A. Goonetilleke commented on the significance of the book to Sri Lanka.

Mineka P. Wickramasingha ( Mickey) is an adherent of the Yoga and Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo Ghose and The Mother of Pondicherry, South India, and took to serious writing as a part of his spiritual discipline. In 1995, he published a collection of stories titled The Playmate.  The breadth of his concerns is evident at a glance at the headings of the different sections of this book which Marshal Fernando, Director of the Ecumenical Institute for Study and Dialogue, has so ably compiled: Church and Its Mission; Interfaith Relations; Church, Politics and Development; Social Justice; Asian Perspectives; Contemporaries; Ethnic Relations. Fittingly, these chapters are preceded by Bishop Lak’s Enthronement Sermon given when he formally took over as Bishop of Kurunegala in 1963, and conclude with his final Pastoral Address made 20 years later, prior to his death in 1983.

The breadth of his concerns is evident at a glance at the headings of the different sections of this book which Marshal Fernando, Director of the Ecumenical Institute for Study and Dialogue, has so ably compiled: Church and Its Mission; Interfaith Relations; Church, Politics and Development; Social Justice; Asian Perspectives; Contemporaries; Ethnic Relations. Fittingly, these chapters are preceded by Bishop Lak’s Enthronement Sermon given when he formally took over as Bishop of Kurunegala in 1963, and conclude with his final Pastoral Address made 20 years later, prior to his death in 1983.