|

17th May 1998 |

Front Page| |

The making of God King-part IV

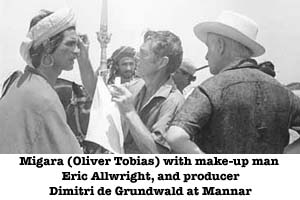

Continued from last week The final curtainBy Richard BoyleThe post-production of The God King took place in London, to where Lester and Sumitra Peries headed to edit the film. Manik Sandrasagra, Vijaya Kumaratunga, Ravindra Randeniya and Joe Abeywickrema came to London too, and were holed up in a minute flat off Lancaster Gate. Ravindra had just got engaged to his Preethi and was hopelessly lovesick. Joe wanted to get his eyes checked and so I organised an appointment with a specialist. I also arranged a camera and cameraman for Manik, who had decided to take some footage of Vijaya driving through the Sussex countryside and horse-riding over the Downs for a future but never-realised project. Nimal Mendis, who was working and residing in London, was asked to compose the music for The God King, and what a compelling score he wrote.The music was to be orchestrated and conducted by Larry Ashmore, who had worked on another epic - Stuart Burge's Julius Ceasar (1970), starring Charlton Heston and John Gielgud. The musician Jon Keliehor was hired to arrange the Kandyan drums.It was deemed by Dimitri that Sumitra's first cut was too slowpaced for Western audiences, so he asked an editor by the name of Rex Pyke to see whether he could improve things. Pyke, who had edited a few English features such as Jack Clayton's Our Mother's House (1968), responded by leaving chunks of the film on the cutting-room floor. One day, while Manik was watching Pyke at work, the editor turned to him and asked what percentage he had in the film. When Pyke heard the answer, he pointed to the endless coils of celluloid on the floor and replied, "Well, there it is now!" Unfortunately, Dimitri was not happy with Pyke's efforts. This time, Dimitri took no chances by hiring Russell Lloyd, one of the most experienced and accomplished editors in the business. Lloyd's first credit as editor was way back in 1937 on William Howard's The Squeaker. Other films edited by him in his early career included Julien Duvivier's Anna Karenina (1948) and Lewis Gilbert's The Sea Shall Not Have Them (1954 ). From the mid-1950s Lloyd became John Huston's preferred editor and had worked on most of the celebrated director's films of the period, such as Moby Dick (1956 ), Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (1957 ), The Unforgiven (1960), Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), Sinful Davey (1969) and Macintosh Man (1973). Yet another editor by the name of Robert Richardson was also involved. In the end there were just too many people, opinions and influences for the film's own good, and although Sumitra had a hand in throughout, it was her original vision that suffered the most mutilation. Needless to say, it became a protracted post-production due to the events at the cutting-table and the complexity of the musical score. Ray Torin, meanwhile, was getting increasingly agitated at the escalating budget. At last, however, Dimitri was satisfied with the final product and The God King was finished. Lester, especially, could relax once again. Reviews of The God King appeared in a number of film journals in England during the spring and early summer of l975. They were reasonably favourable, all things considered, and Lester and Willie were singled out for their contributions. "Peries' visual flair is one of The God King's major assets," wrote Derek Elley in the June 1975 issue of Films and Filming, "and he receives devoted support from cameraman Willie Blake and the Eastman colour processing, suffusing the screen in a ravishing display of reds, saffrons and golds. Memories of Conrad Rook's Siddhartha (1972) are strong indeed, even if the film lacks the latter's spiritual depth: visually, it is its equal, and in design and in staging Jerzy Kawalerowicz's Pharoah (1966), is frequently evoked". "Like Satyajit Ray, with whom he is frequently compared, Peries is, by his own account, concerned with nuances of feeling, the avoidance of theatrical flourishes and with the discovery of drama in the seemingly undramatic. It is slightly surprising, therefore, to find him with The God King working on a relatively big budget, international production, and in an epic style he has only attempted once before in "Sandesaya", wrote Verina Glaessner in The Monthly Film Bulletin of June 1975. Glaessner went on to qualify her surprise: "In other ways, The God King is not completely dissociated from Peries' previous work: the violence is accomplished discreetly, with the expected battle sequences yielding to scenes of personal confrontation, and the central characters might as easily be members of a closeknit, if fraught, family unit as pawns in a predestined drama. The final impression is one of grace; Peries is a remarkably fluid director." Derek Elley claimed that "Peries' viewpoint is epic where others might have been purely illustrative; his set-ups and use of the wide screen have a firmness which gives each sequence, whether brief or not, an epic quality; characterisation is also in this vein, and the players, though fully-drawn in terms of outlook, stance and moral behaviour, have the required epic detachment as figures moving through a historical tapestry. Dialogue is sparingly used, most often in the form of pronouncements rather than ordinary speech; this, with the picturesque and well laundered look of the costuming, gives The God King an almost celebratory air in expounding its theme." Having all but vindicated Greville-Bell's script, Elley went on to write positive things about other aspects of the production: "The central palace set, spacious and imposing, lends itself to an infinite number of stylish visuals, and Nimal Mendis' score - featuring such disparate styles as baroque, fugue and souped-up Seventies orchestration - has an attractive, and ultimately moving, theme at its heart. The God King, despite its faults (non-technical), has an openness and freshness which is very appealing." "Geoffrey Russell is excellent as the imposing and monomaniacal Dhatusena, Oliver Tobias sinister as the wheedling military chief and Leigh Lawson in the title role shows surprising talent prior to his unhappy association with Percy's Progress. All three, authentically-tanned and exotically garbed, are convincing in their Sinhalese parts and Lawson especially overcomes his early inadequacies with some fine later playing of Kassapa's spiritual conflicts." Elley was struck by what he thought was the nationalistic and didactic tone of the film. "The God King, in the best tradition of film epics, is explicitly relevant to the present time" he wrote. "Ceylon officially became Sri Lanka in 1972, and the film is very much a celebration of a country's achievement. The intensely nationalistic tone, the conflict between traditional monarchy (Dhatusena) and representational government (Kassapa), and the frequent a priori prophecies of the country's future, all give the film a distinctly didactic flavour. Dramatically, this works in its favour by providing a strong central core for events to revolve on; in filmic terms, the themes are sufficiently universal for them to bear repetition." Unfortunately, not everyone was as enthusiastic about the film as Mr. Elley. Verina Glaessner, for instance, detected two major weaknesses: "Probably most to blame for the film's inevitable flaws are the way the project has been Anglicised: the three lead players are British and despite their capable performances, they can't help but bring to mind a kind of Hollywood hokum at odds with the essential fascination of the local legend. Similarly the literate script comes uncomfortably close at times to a kind of Shakespearean pastiche, particularly in relation to Dhatusena. This tends to leave the problematic figure of the swami without any perceptible context, and deprives the film as a whole of any commitment to myth, folklore, politics, or history." The script also came in for harsh treatment by the reviewer in Cinema TV Today of 5 April 1975: "The visual excitement is not matched by the literary script, which is filled with explanatory speeches that fail to throw any light on the story. Indeed, historically accurate though it presumably is, the plot becomes well nigh incomprehensible. Directed at the measured pace of a religious procession, the film is an elaborately decorated conundrum with too few clues." However the reviewer also commented that the film was "very beautiful and spectacular, like a series of handsomely staged tableaux" and thought the business predictions for it were "fair to average generally; good in very carefully selected smaller cinemas", where minority audiences "look for something unusual and are interested in the ancient customs of other lands." Scotia-Barber, the distributors of The God King in England, never did the film justice in terms of release and publicity. They certainly did not take heed of the reviewer's opinion that selected smaller cinemas would be best for the film. It ended up being on the wrong half of a blanket double-bill with William Friedkin's hit, the Exorcist (1973). Bizarre events were to dog the film even in its distribution and exhibition. A few years later, The God King ran for many months in a small cinema on the Left Bank in Paris. Its title had been changed to the Tomb of the Maharaja and Lester's name had been removed from the credits as director and Anthony Greville-Bell's substituted. How this blatant piracy was perpetrated is unclear. "This is a very serious offence in France," Lester comments, "but it's difficult to track down the culprits - they are bankrupt and in hiding." That Lester's name was dropped in favour of Greville-Bell's may have had something to do with an attempt to Westernise the film further. It harks back to an unpardonable mistake made by an American journalist, Quinn Curtis, in a location report filed during Greville-Bell's short-lived term as producer. Writing in the New York Herald Tribune, Curtis claimed that Greville-Bell was directing The God King - but then he also claimed that Dimitri was son of Anatole de Grunwald.

Despite the general approval of the critics, The God King was hardly a resounding box-office success. So what good came out of all those months of toil by so many people? Most important was the fact that the production had not been abandoned, for as Lester points out, "If we had allowed the film to collapse, it would have been a setback to the whole Asian cinema." Instead the film proved that collaborative co-productions were possible, and that Sri Lankans could deliver the goods. The God King laid the foundation for future foreign film production made here in local collaboration with Chandran Rutnam's Film Location Services. It was a training ground for some of the key local production personnel involved in this aspect of the film industry, such as Errol Kelly, Rita de Silva, Raj Perera, and D.B Warnasiri, as well as those who have made their mark in similar areas, such as Senake de Silva. On a personal level, the film provided an opportunity for Lester to demonstrate that he is much tougher and more determined than is generally realised. "It came to a stage where I would have seen that film through on my knees for nothing," he states. Indeed, without him the production may never have been completed, for as Manik rightly says, "No other Sri Lankan could have stayed through that production, but Lester had the sagacity and resilience to do so." It seems appropriate that I should carry out a 'where are they now?' check on members of the British cast and crew. I used to see Leigh Lawson and Oliver Tobias regularly in the 1970s. It was during this time that Leigh Lawson left his first wife and married the actress Hayley Mills. However the marriage did not last and now he is partner of the 1960s supermodel, Twiggy. Leigh has enjoyed a consistent if unspectacular career as an actor, having appeared in such films as that awful phallic homage, Ralf Thomas' Percy 's Progress (1974), Roman Polanski's Tess (1979), and John Schlesinger's Madam Sousatzka (1988 ). He has also acted in many TV productions, most notably QB VII (1974 ) and Disraeli (1979).

I have no news of either Geoffrey Russell or Bill Kirby. Herbert Smith and Gus Agosti worked together on James Fargo's Game for Vultures (1979 ). Gus Agosti, died in the early 1980s and Herbert Smith has now retired from the film business and owns an antique shop in Arundel, Sussex, where I have met him several times in recent years. I am informed that Eric Allwright worked until the late 1980s on such films as John Sturges ' The Eagle Has Landed (1976), Ivan Passer's Silver Bears (1977), John Badham's Dracula (1979) and Richard Attenborough's A Passage to India (1986). After his encounter with The God King, Russell Lloyd went back to work with John Huston on The Man Who Would Be King (l975), as well as cutting films for other directors, such as Anthony Page on The Lady Vanishes (1979 ), Piers Haggard on Peter Sellers' last movie, The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu (1980) and Julien Temple on Absolute Beginners ( l986). Larry Ashmore has orchestrated some interesting films over the past decade, including Frank Marshall's Arachnaphobia (1990), and Kenneth Branagh's Frankenstein (1994 ) . Lester is absolutely right when he says that, "The story of the making of The God King deserves a book regardless of the film's quality." Sorry, Lester, I am unable to go to such lengths, but I trust my account will suffice until such time as that book is written. And I hope it has done justice to this extraordinary but sometimes unhappy episode in the history of Sri Lankan Cinema . |

||

|

More Plus * Heavenly isolation

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports | Mirror Magazine |

|

|

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to |

|

It

was July 1976 before The God King was finally released in Colombo

at the Liberty cinema. The wordy newspaper advertisement claimed, "The

Mahawamsa says that Kassapa killed his own father, King Dhatusena. Latter

day historians have shown Kassapa as a lover of beauty and a King sensitive

to aesthetics but a victim of intrigues. Dimitri de Grunwald's film introduces

a new and controversial element of Hindu intervention in Sri Lanka in the

form of a Swami, who brings the concept of Divinity to the Sinhala Court."

However, Swami Gauribala, who it will be remembered, was the inspiration

of the film, considered it to be a total abomination. As he left the screening

he proclaimed: "What is sacred is secret!"

It

was July 1976 before The God King was finally released in Colombo

at the Liberty cinema. The wordy newspaper advertisement claimed, "The

Mahawamsa says that Kassapa killed his own father, King Dhatusena. Latter

day historians have shown Kassapa as a lover of beauty and a King sensitive

to aesthetics but a victim of intrigues. Dimitri de Grunwald's film introduces

a new and controversial element of Hindu intervention in Sri Lanka in the

form of a Swami, who brings the concept of Divinity to the Sinhala Court."

However, Swami Gauribala, who it will be remembered, was the inspiration

of the film, considered it to be a total abomination. As he left the screening

he proclaimed: "What is sacred is secret!" Oliver

Tobias is the only member of the British contingent to have returned to

Sri Lanka - which he has on several occasions to act in German television

series shot partly here.

Oliver

Tobias is the only member of the British contingent to have returned to

Sri Lanka - which he has on several occasions to act in German television

series shot partly here.