Year on the Web

Year on the Web Year on the Web

Year on the Web

The scenery on the way to Ritigala, a holy mountain in north-central Sri Lanka, had been pastoral,with emerald green paddy fields stretching out from either side of the road, adorned with feasting storks and snow-white egrets But here within the precincts of Ritigala’s strict natural reserve, the view was of darker shades of green complemented by dark brown tree trunks, silent sentinels, stilled at this early hour. The mountain now towered above us like a geological Tyrannosaurus Rex. Even its lesser peaks were hidden by clouds amid a darkened sky.

There was nobody else around, understandably so, for it was 9 a.m. on the day before Christmas,

It felt wrong to me, a Lankan recently returned from the West, to have been dragged out of bed at 3 a.m. after an all night X’mas party, for a six hour road trip to climb a mountain. Why had I agreed to this masochistic exercise, when I could have been sleeping the party hobgoblins away in my bed in Colombo, more than 160 kilometres away?

The answer was in the back seat of the pick-up truck, tying up loose ends in his rucksack. Cedric, the man who was responsible for my sense of imminent dread, was - and still is - a legend. In an earlier era, he would have been another Roy Champman Andrews (the role model for Indiana Jones), another Chuck Yeager.

I had travelled both high mountains and high seas with him, and each time it was like a natural high. Each time I came away swearing that I loved life too much to ever risk it again with this lunatic; and yet, here I was again, a moth to the flame, thinking blearily of bed, breakfast and running water. At least this last wish would be answered soon, for the skies threatened rain.

But up there, hidden among those clouds 660 metres up, was a unique mountain forest ecosystem, containing a whole host of endemic plant species. Well off the beaten track, the jungles of Ritigala also hosted wildlife such as sloth bear, leopard, sambhur, leaf-eating langurs and a herd of elephants.

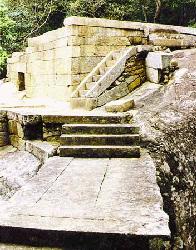

The mountain’s history also lent it a certain majestic aura, a quality of brooding hidden power. On its lower slopes are cyclopean ruins built of granite - sluices, giant ponds and some mysterious structures which looked like great meditation platforms.

At one point in the Indian epic of the Ramayana, during the battle against the evil Ravanna whose redoubt lay in Sri Lanka, the monkey-king Hanuman is sent to find a rare herb from the Himalayas in order to heal the injured Lakshman, Rama’s brother. Hanuman, not being hemmed in by niceties, brings back a whole segment of the Himalayan massif, pieces of which fall in three places in Sri Lanka. Ritigala is one of these locales, according to the myth, and it is famous for its medicinal plants and unique flora.

Several millennia later, although before recorded history began in Sri Lanka, Pandukhabaya, the legendary pre-Buddhist founder of the Anuradhapura civilization, hid out at Ritigala for eight years as a young prince hunted by his uncles who wanted the throne of the northern kingdom. According to legend, he gathered together an army consisting of the mythical Yakshas, now identified as a grouping of indigenous hunter-gatherers, and broke out of his mountain fastness to slaughter all his relatives and take the crown. He founded the great Dynasty, the Mahavamsa, which built Anuradhapura into a flourishing South Asian hub city. So this had been where it all began, and the ancient kings had landscaped the lower slopes over the centuries and built monasteries and meditation centres for monks.

The ancient kings had paid attention to the environment and had realized

the importance of protecting watersheds and forests. Here in Sri Lanka had

evolved a civilization centered around giant dams with stone sluices, marvels

of hydraulic engineering which caught the waters from the monsoon rains and

sustained the population for the dry months. These dams were built to last,

with granite and other forms of rock being used as building material, many of

them at least 2000 years old, in contrast with the mega-disasters being built

today, with millions of aid money. It was a great paradox to be reminded of past

civilizations and their skills, then to look at the reality of today.

The ancient kings had paid attention to the environment and had realized

the importance of protecting watersheds and forests. Here in Sri Lanka had

evolved a civilization centered around giant dams with stone sluices, marvels

of hydraulic engineering which caught the waters from the monsoon rains and

sustained the population for the dry months. These dams were built to last,

with granite and other forms of rock being used as building material, many of

them at least 2000 years old, in contrast with the mega-disasters being built

today, with millions of aid money. It was a great paradox to be reminded of past

civilizations and their skills, then to look at the reality of today.

At the time we visited Ritigala, it was the end of 1991, and the island was slowly recovering from nearly five years of savage blood-letting in the south. The urban Marxist guerrillas of the JVP had clashed head on with the State, and the dead numbered in excess of 50,000 people. This was a war separate from that waged by the Tamil Tigers in Jaffna, which had see-sawed across the east and north since 1983.

All that seemed far off this morning. There were three of us, including Cedric’s eldest son Jason, and we had to start climbing before the rains began. Few people from Colombo had climbed this peak, due to its remoteness and the local villagers didn’t go up it much either, partly due to the legends surrounding it, and because they had better things to do with their time, like surviving.

I had once considered archaeology as a profession, and had worked at Anuradhapura for a year or so, having been attracted by the mysteries of Ritigala. Cedric was an avid explorer of Sri Lankan terrain, and he knew the mountain’s flora and fauna much better than most. He had a map in his Colombo house which had pins for the places on the island he had not been to. This was one of them.

So we began climbing, having no idea where we were going. We had a sort of

guide, a youth from a nearby village who had suddenly descended on us in the

hope of making a quick buck from these crazy Colombo urbanites. He professed to

know the way to the top. This would be a cake walk with a local man guiding us,

I thought. Then the rain started pelting down. The slope turned slippery and

true to legend, didn’t take kindly to being climbed on. Our guide soon

became utterly lost. Cedric took the lead and eventually we found ancient

rockcut steps leading up to the rocky summit, with a view which would have been

stunning on a clear day.

Of all the people I have ever met, Cedric stands out as unique. Adventurer, naturalist, bonsai enthusiast and plant nursery keeper. An amateur herpetologist, he liked to collect snakes - a major source of irritation to his wife : playing hostess to a Green pit viper, an albino cobra and a Russell’s viper, two of the most toxic snakes in Sri Lanka was no party, but being married to Cedric prepared her for the unusual. He has been immortalized by having a fresh-water fish species, Punteaus, named after him, having discovered it in the highlands of Sri Lanka. And his love for Sri Lanka was absolute. He would stay on the island through all its traumas, scorning the desire for flight to more stable climes.

A naval officer, Cedric had been part of the Smithsonian Whale Project which ran surveys in Sri Lankan waters in the early 1980’s and had swum with whale sharks, sperm whales and seen blue whales at close quarters. I first met him later that decade when he was recruited for an underwater archaeological survey for ancient wreck sites in Sri Lankan waters. He became the key figure for that survey, helping to lay the foundations for future exploration and excavation work.

After climbing Ritigala, we came down in another two hours, full of euphoria. We spent the night at the old Archaeological Department office at the foot of the mountain. The rain stopped that night, but most unnerving was how silent this neighbourhood was. We had a little lamp for light and some torches and it was easy to believe that civilization was a distant promise. The mountain had a presence, a tangibility which scraped at our atavistic senses.

The next morning, we washed in a crystal jungle stream and Jason enthused about building a house in Ritigala someday. As we departed, we stopped on the road out to take a last look at Ritigala : that moment in time became fixed in my mind. The green rice paddies and quiet bubbling of rivulets lay in contrast to the wild majesty of the mountain. It was a footprint from a different time.

Now, in 1997, it is a very different world. Both Cedric and his son Jason are gone, victims of a senseless war. Jason was cutdown in his prime while serving as crew on a Russian transport plane which crashed into the Indian Ocean west of Colombo in 1995.

Cedric disappeared into the eye of the war raging in northern Sri Lanka. He went missing in action about a year ago when a short routine helicopter flight was brought down by enemy fire. Officially, everyone on that flight was presumed dead, but there are unofficial eyewitness accounts of someone matching Cedric’s description being taken prisoner. Unofficial reports suggest there may be as many as 10,000 personnel gone MiA since the war began. In Cedric’s case, his family and friends are convinced that he is alive.

The Tamil Tigers are keeping mum, and the government’s policy towards armed forces personnel taken captive, well, there is no policy. MiAs only receive official attention if the immediate families make enough waves. Indeed, the official line is that it has been a "clean war", without civilian losses, a sign of government hypocrisy which does not bode well for the future.

Friendship is a touchstone, a constant in a sea of change. In the paradox that is Sri Lanka, Cedric was a true constant, akin to the Great Basses Lighthouse. With his disappearance I lost my faith in my ability to weather further storms, and the ability to enjoy the langourous lifestyle which, in spite of the war, is still a reality in Sri Lanka. That is one of its many paradoxes. Another is the presence of so much natural beauty side by side with so much death and trauma.

A library for school children will be opened today at Maitri School. Muriyakandawala, at the foothills of Ritigalakanda, in memory of Jason Martenstyn who was killed in action in 1995. Today would have marked Jason’s 25th birthday.

Continue to Plus page 4 - Contest of man and beast: the saga of Rampage

Return to the Plus contents page

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to

info@suntimes.is.lk or to

webmaster@infolabs.is.lk