Who goes there?

Midnight at Kanatte!

As the brilliant half-moon glides behind a bank of clouds in the sky over Borella, we are walking deep into the ‘Land of the Dead’ where lie the mighty and the meek, the rich and the poor. Equal before that great leveller, Death, men, women and children, whatever race or religion — who went about their daily routines like all of us, who loved and hated, fought and made peace, — are now “dust to dust” or “ashes to ashes”.

Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Intrigued by all those stories of ghostly happenings we have heard over the years and the numerous movies on paranormal activity which have terrified us, a Sunday Times team walks into Kanatte on Wednesday night.

Two dogs of questionable lineage protest over our presence at the main entrance to Kanatte on Baseline Road. They are inside and we are outside the huge wooden doors shut tight for the night with a similarly huge padlock. Night Keeper, Bope Ranasinhage Sunil, 57, immediately appears and after ensuring that we have permission, lets us in.

Eerie it is with some parts of Kanatte lit well, while other sections are pitch dark, the huge trees taking on strange shapes and the white tombstones of varying shapes and sizes, some crosses and other sculptures of heads, angels and even a sitar sending the imagination down scary thought-pathways.

There is a chill-wind, with the stillness of Kanatte being disturbed only by a peculiar rustle of leaves and the persistent and insistent sound of the cicadas. The walkabout begins along the straight and narrow main path, with the eyes and the mind darting here and there and “seeing” shadows and objects which fuel the imagination.

Sunil: Recalling spooky happenings

When walking from the gate, in the distance, close to the crematorium towers, is that a human form, awaiting our arrival? Closer we go, treading with slight trepidation. Relief comes as we see the builtup bust of the first Municipal Commissioner and no “other”. A little coaxing and Sunil, our guide, launches into the “happenings” here, while taking us towards a clearing where glows red, some embers.

“This corpse is burnt now,” says Sunil as he stokes the flames gently — a routine job for him as he does not want to inconvenience the dead person’s loved ones when they come the following day for the ashes. There are spirits moving around at night at Kanatte and they deserve the respect of humans who are alive, Sunil reiterates.

Do you know that when you eat food at Kanatte, it does not taste the same as when you eat it outside, he asks, answering with a sweep of his hand that he usually “shares” his dinner with “those” hovering around. They need to be fed too, he smiles, relating how usually-delicious bedapu kumbalawo are insipid with no aroma when eaten inside Kanatte. The same applies to pork, other meats and even a buth packet.

Many are the times he has also seen women draped in white sarees standing by tombstones and vanishing into thin air as he approaches, leaving him to stare at the huge photographs that relatives of some dead people have embedded onto tombstones.

For 16 long years, Kanatte has been Sunil’s workplace and he knows it like the back of his hand. Dubbing the time between midnight and 2 a.m. as the “peak” when “they” are about, he says that suddenly he would feel a presence passing and would “horen” cast a glance in that direction. It would be thereafter that he would direct the beam of his torch to the area.

In the early days of his job, he would patrol the less-traversed areas around 2 a.m. because that was the time flower-thieves descended on Kanatte. He remembers like yesterday how he was walking past the Buddhist Hall at 2.30 a.m. and felt a slight drizzle and saw the other watcher going towards the gnarled Na-gaha, with his paata-paata kude. Sunil followed him calling out his name, but to his consternation there was no one. Assuming that the other watcher was playing a prank on him, he had made his way to his post near the crematorium, only to find that he had not budged from the place as he was running a high fever along with bouts of shivering.

Human forms are not the only ones that Sunil has seen but also beautiful rabbits and porcupines. But the image imprinted on his mind is that of a big, brown dog, making me think of ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’.

Eyes becoming wide even at the very thought of this huge dog with a long muzzle and a bark that rumbled and sent shivers down his very being, Sunil says that the strays that he had befriended at that time would cringe in fear and with tail between the legs hide wherever they could. It was after a few of them were viciously attacked by this dog that some of the watchmen lay in wait with clubs and attempted to beat it.

“However much we tried to hit it, the blows wouldn’t fall on it,” he says, adding that the dog leaped over the wall and disappeared into the night. The crematorium brings its own sounds, he says, for as the night advances there would be heavy footsteps of people on the tiled floor doing the turn around it. The sound of footfalls, but no people.

Different points of Kanatte bring out different tales. Never can anyone sleep on the marble slab in the Buddhist Hall, for that person is violently thrown to the ground, says Sunil who in the dead of night would sit near a famous singer’s tomb where 42 of his songs are engraved and listen to the songs on his (Sunil’s) mobile phone.

Abruptly he stops at the junction where four pathways meet and says, “Here’s the place the ghosts hold their resveem (meetings),” at which time suddenly a bat flies low and in the distant darkness we see the glow of a few fireflies as if eyes without bodies are staring at us.

Moving forward, Sunil halts beneath the heavy canopy of a Na-gaha and calls it a “balavath sthanayak” (a powerful place), while also holding forth about the sounds he has heard – a large stone crashing down and the shriek of a child among many others.

It is another cemetery veteran, S.J.S. Fernando aka ‘Kalu Aiya’ who shows us around at noon on Wednesday, pinpointing the graves of well-known people. Kalu Aiya, 71, has 40 years experience. According to him, he laid to rest his fears after he worked at the mola (crematorium) for six years. Among the numerous cremations he has carried out is that of Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna Leader, Rohana Wijeweera.

He has worked at the mortuary, the shed just beyond the main gate where in the early days bodies had been brought to be embalmed because only Raymonds had the licence to do that. The corpses would be brought in old boxes, embalmed and then deposited in new coffins and taken to the funeral parlours, he says.

Kalu Aiya remembers the time a group of rationalists decided to spend the night at Kanatte. Chuckling he relates how they could not “survive” long at the cemetery as they were suddenly showered with sand and pelted with stones by unseen forces.

For him, of course, one encounter is seared into his memory. The day’s work was over for him and his immediate boss, B.A. Thomas Perera, who is no more. As twilight was deepening into night, having bathed and locked up the crematorium, they were heading past the Buddhist Hall towards the gate of the Roman Catholic section, when Kalu Aiya looked back and saw a smartly-attired mahaththaya in a white suit and hat, a little distance behind them.

Thinking that the gentleman may have come to get a grave and seeing an opportunity to make a quick buck, Kalu Aiya had headed back. Twenty-five cents was the usual “pagava” (bribe) we would get, he says, adding that 50 cents would be a “loku ganak” which would allow them to have a kahata as well as a smoke.

Hurrying back to the small bo-tree, when Kalu Aiya got there, the maththaya had vanished. Looking up, he had then spotted him walking briskly, “pata-pata gala” towards the main entrance. Rushing up to Thomas, when he mumbled about the mahaththaya, Thomas had laced him “a kane” (thundering slap), without a word and walked out of the cemetery, dragging him along.

It had been next morning when Kalu Aiya went to work that he found Thomas with a knot of workers near the Na-gaha. The other-worldly tale had then unfolded that the mahaththaya would lead gullible workers to the mortuary and walk through the wall. The workers, gripped by fear, would fall in a faint, injuring themselves, sometimes seriously.

The workers at Kanatte say with one voice that spirits roam the grounds but it is important for humans to “pin denna malavunta” (Give merit to the dead). Their thinking is simple – Live and let live.

A curator’s experience

Kanatte, covering 48 acres, comes under Cemetery Curator G.A. Chanaka K. Perera who has followed his father, G.A.S. Perera’s footsteps into the job. Chanaka explains that it is not only Kanatte, with its address of 1, Elvitigala Mawatha, Borella, Colombo 8, that comes under the purview of the Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. Pradeep Kariyawasam of the Colombo Municipal Council, but also Madampitiya in Colombo 15, Jawatte in Colombo 7 and Kirulapone in Colombo 6.

G.A. Chanaka K. Perera

Kanatte is divided into a Buddhist/Hindu section which has within its fold the Japanese cemetery; the Roman Catholic section; the Anglican section; and the General Christian section which includes the war graves.

This cemetery which had its beginnings in 1866, has 30,000 ‘purchased’ graves; about three times more ‘common graves’; and 10,000 graves where ashes are interred, according to Chanaka, who explains that corpses are buried in 4’X9’ pits and ashes placed in 2’X2’ pits.

There are two new crematoriums, two old which have been repaired and two new ones which are to be established. Although about 70 employees are needed to carry out the numerous tasks there are only 35, the Sunday Times learns. Having given us an insight into the running of the cemetery, Chanaka vividly recalls the day a couple who had died in a freak accident was buried at Madampitiya when he was in charge there.

The couple had died when the petrol shed at which they had stopped to get fuel collapsed on their car. The funeral was over and many wreaths were around the double graves and candles flickered in the twilight. Chanaka was in his home in the middle of the cemetery and through the large windows saw the mal wadam parting, as if someone had suddenly stood up from a crouching position.

It was then that he called his mother and brother and as they watched, an ahu tree near the new graves began shaking violently, followed by a mora tree closer to their home, he says, recalling the jidi-jidi noise. The tree movements lasted only about 2-3 minutes. Soon after, the three of them rushed to the graves and saw a long crack snaking along the earth from them.

He has always noticed a change in the environment when there is a burial of a person who has died in a violent episode.

There would be a rush of rain, even without any dark clouds or a branch would crash down, he says, thinking back to a funeral when the corpse could just not be buried. While the cortege was on the way, a massive tombstone fell into the newly-cut grave and a crane had to be brought to extricate it. But while that operation was underway, a sudden, heavy shower came down and the crane got bogged in mud.

Chanaka too echoes what everyone linked to cemeteries tells us: “We must respect the dead.”

|

Weird or what! Did we cross a time zone, is the spooky question on our minds after our tryst with the dead on Wednesday. Having walked the length and breadth of Kanatte, we slowly make our way back, stopping for about 15 minutes for a final set of photographs. The dogs have run into the darkness and we hear them barking in the distance at nothing in particular.

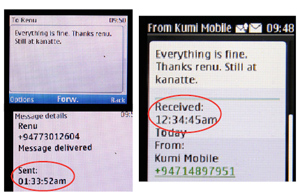

Grumbling that something is wrong with my mobile, I decide to set the right time on my way back in the vehicle. I reply two SMSs I have received, at Kanatte itself and we wind up our assignment, walk out of the gate and get into our vehicle. Startled, I am for when I look at the mobile, the time is 12.50 a.m. On Thursday morning in office, when I mention the time issue, my colleague suggests we check the times of the messages. To our disbelief, here is what we found:

‘Open’ remains the verdict on the weird mystery of the time lapse. Is there an explanation out there? |

comments powered by Disqus