Columns

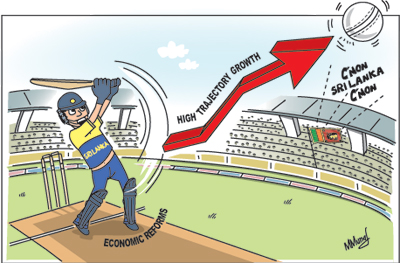

Challenge of sustaining high economic growth

View(s):Sustaining economic growth at 8 per cent has turned out to be more difficult than anticipated. Treasury Secretary P.B. Jayasundera reduced the expected growth this year to 6.5 per cent. The Central Bank reduced its estimate of growth some time ago to 7 per cent and revised it at the end of September to 6.8 per cent. A Standard Chartered Bank research report expects Sri Lanka’s economy to grow by 6.8 per cent this year but recover to 7.5 per cent next year.

Other estimates place the expected growth closer to the 6 per cent mark. These are perhaps more realistic in a situation when global economic growth is tardy. Countries such as India and China that have been growing rapidly at double digit levels have revised their growth to around 5 per cent. The Central Bank of Sri Lanka has been reluctant to revise growth rates downwards although economic performance is deteriorating.

Whatever the precise statistic of growth will turn out to be, there is little doubt that the economy has had a jolt and that growth has declined by about 2 percentage points. The decline in exports owing to global conditions has had a greater adverse impact on growth than the drought that has been an unmitigated disaster to the livelihoods of farmers. The drought has also affected the trade balance owing to the higher imports of oil.

Difficult task

More important than the growth statistic for this year, there are questions raised as to whether a high growth momentum could be sustained within the current economic policy framework. There is growing doubt that the policies pursued by the government could maintain a high trajectory of growth.

Sustaining economic growth at a high trajectory is difficult owing to many reasons. First of all there is a statistical problem. It is one thing to grow at a high rate from a low economic output. It is quite another to grow at high rates once the economy has grown. The 8 per cent growth rate achieved in 2010 and 2011 was very much the result of several economic sectors and regions growing rapidly after the end of the war. That peace dividend may be fading away.

Economic revival

The revival of economic activity in the East and the North of the country gave a big boost to economic growth. In fact there were inadequate statistics of output in this region to estimate the real growth in output after the end of the war, but there was no doubt of an upsurge in production of goods and services once peace was achieved. These regions have much potential for growth and it is likely that their increased output would contribute much to future growth as well.

Several economic activities that were affected by the war and security conditions were able to perform much better. The revival of fishing that was severely affected by security conditions made an important contribution to growth. However, now that fisheries sector has recovered its lost potential the growth in fisheries must depend on intensive strategies that require investment. Therefore, the rate of growth in fisheries output will not be an autonomous one, as it had been in the previous two years. Yet there is potential for the expansion of fisheries with better technological developments.

Agriculture too had a boost as the unsettled conditions in several areas of the North and East resulted in a loss of area cultivated. The marketing of agricultural produce of the North also suffered a setback and its backward linkages to production were restricted. The glut in vegetable production witnessed recently is evidence of agricultural growth in the North. Trade and commerce and tourism in the North and East are reasons to expect these to contribute to growth despite unfavourable global economic conditions and a severe drought.

Tourism gained immensely from peaceful conditions. Tourist arrivals expanded since the end of the war and are heading towards or even beyond one million tourists this year with direct earnings from tourism reaching around US$ 1 billion. The growth in tourism has boosted other sectors of the economy to which tourism has backward linkages.

Infrastructure

Another reason for the boost in national output in the post-war years has been the large investments in infrastructure development. Although the returns to these investments would necessarily take time and even though some infrastructure investments may not bring in returns, yet the cost of the investment itself contributes to the growth statistic. The funding of these mega investment projects have been made possible largely due to foreign borrowing. This too could be limited as the foreign debt has risen to very high levels and the large infrastructure investment is straining the trade balance.

Policies for growth

There can be no doubt that the country’s output increased significantly after the war. However, the full potential of the peace dividend has not been realised owing to poor policy thrusts, lack of reforms in public sector institutions, disrespect for law and order and an inhospitable investment climate. Further growth in the economy would depend on improving these areas and creating a policy environment that encourages higher investments.

If the economy is to reach a higher growth rate than merely achieve the results of the peace dividend, it is vital that fundamental policy changes are put in place. Foremost among these requirements is the need to reduce the fiscal deficit progressively to 5 per cent of GDP in the next two to three years. This requires broadening the tax base and implementing tax reforms and improving the efficiency of tax administration.

There is a need for tariff reforms that would encourage exports.On the expenditure side the vast amount of subsidies given to public enterprises must be drastically reduced. This implies significant reforms of public sector institutions, as well as a strong resolve by the government to stop financing loss-making enterprises, especially Sri Lankan Airlines and Mihin Air. More prudent government expenditure is vital.

There should be a serious effort to ensure law and order and develop a society based on the rule of law. There should be a guarantee of private property rights and the rescinding of legislation that is a threat to private enterprise. State intervention in private enterprises and financial institutions must be discontinued. These are but a few fundamental policy thrusts that are needed to enhance savings and investment. Unless these are put in place there is little scope of sustaining high growth rates.

Summing up

The downward slide in the economy should be an opportunity for rethinking of economic policies and bringing about a new wave of reforms. It is a time for pragmatic economic policies that ensure fiscal consolidation, expand exports, reform public enterprises, reduce conspicuous wasteful public expenditure and promote policies that inspire investor confidence by ensuring law and order, the rule of law and guarantee private property rights. The alternate is low economic growth.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus