Has a boon turned into a bane? Since time immemorial, humans have striven to “better” their lives, moving from forests to dwellings along waterways, gradually setting up villages and finally building towns.

Even now the yearning among many is to leave behind the village or the rural environment not only for the glitter and glamour of the town or the urban area but also for the easy lifestyle that beckons.

What does this entail especially in the context of diseases? This is what five doctors, two local and three foreign, attempted to find out in a research done right here in Sri Lanka, covering 100 villages in seven provinces out of the nine in 2007-2008. ‘Quantifying urbanization as a risk factor for non-communicable diseases’ was the aim of the ‘Sri Lanka Diabetes and Cardiovascular Study’ with 4,485 participants and the hard work of the doctors have paid dividends with the publication of the findings in early June in the Journal of Urban Health of the New York Academy of Medicine.

The research team comprises Dr. Steven Allender and Dr. Kremlin Wickramasinghe of the British Heart Foundation Health Promotion Research Group, Department of Public Health, University of Oxford, United Kingdom; Dr. Michael Goldacre of the Unit of Health-care Epidemiology, Dept of Public Health, University of Oxford; Dr. David Matthews of the Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Oxford; and Dr. Prasad Katulanda of the Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo.

Explaining in lay language what the study which is a major eye-opener on urbanization and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is about, Dr. Wickramasinghe says the team used a new tool which can “quantify urbanization in an objective manner”.

Earlier, administrators used an urban/rural dichotomy, with the differentiation of urban and rural being measured in terms of the distance from the city centre, the Sunday Times understands. But this study has developed a seven-item “urbanicity” scale indicating what it takes to call a particular area urban. The seven items are: population size, population density, access to markets, access to transport, access to communications, access to education and access to health services.

Delving into extensive literature of the past, Dr. Wickramasinghe points out that although the association between the increased level of urbanization and NCDs has been discussed, the findings had been criticised as researchers used administrative definitions to define urban and rural areas.

Risk factors including unhealthy diet and lack of physical inactivity are not limited by administrative boundaries, he points out, explaining that his team’s study used an objective scale to measure the level of urbanization. So it has established a new level of global evidence. When there is better evidence, a stronger message can be conveyed to underline the need to address these challenges.

“These issues cannot be resolved completely through individual level interventions. We need to bring appropriate policy changes to create a healthy environment to reduce the burden of these diseases in urban areas,” he stresses, adding, “We believe these results would be useful to drive those policy discussions and to take evidence-based policy actions for health promotion.”

Meanwhile, health inequities in different socio-economic groups and geographical areas have been put under the spotlight at global, regional and national levels in the recent past. The demonstration of existing health inequities in different population groups is the first important step. Sri Lanka was a country partner in the Social Determinants of Health Commission appointed by the World Health Organization to tackle these health inequities globally. Sri Lanka has shown several initiatives to address these health inequities and this would add value to available resources to facilitate this process.

The study which measures the relationship between urbanization and NCDs such as heart disease, diabetes, stroke, high blood pressure, cancer etc., holds up a red signal which the authorities should not only take note of but also act on.

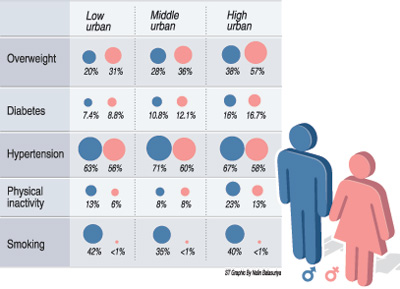

With increased urbanization, there is a higher link with physical inactivity and getting overweight (high body mass index) while there is also a higher risk of developing diabetes mellitus among both men and women.

For thousands, nay millions enjoying the comforts of urban areas including the powers that be, it is time to take note before it is too late. Action to prevent going down the slippery slope of non-communicable diseases is a necessity.

Health interventions a must in urban areas

What should the findings of the survey mean not only to the average Sri Lankan but also to the health authorities who are guiding policy?

Disclosing the backdrop in which the survey findings come, Dr. Prasad Katulanda explains that non-commuunicable diseases have become the most important causes of death and disability in Sri Lanka.

Heart diseases are the commonest cause of death and diabetes, chronic respiratory disease and cirrhosis have become other important causes of death and hospital admissions, the Sunday Times learns.

These conditions which were traditionally seen in older people are increasingly seen in young adults and the middle aged particularly in the urban areas, he stresses, pointing out that it is due to the rapidly changing dietary patterns and lack of physical activities in the urban areas starting from childhood.

“If,” he warns, “serious public health preventive measures are not taken, the NCD epidemic has potential to hinder the country’s economic development as it affects the working age group.”

Since it also affects young parents, it can cause disruptions in the education and development of children in such families with dire consequences on the next generation as well, says Dr. Katulanda.

Therefore, urgent public health interventions especially in the urban areas are a must, the Sunday Times learns.

They should include the promotion of healthy eating habits starting in schools. Junk food and sugar containing beverages need to be discouraged strongly and people educated to cut down on calories to maintain the optimal body mass index and waist circumference, he says.

Meanwhile, facilities to promote exercise such as walking and cycling lanes should be established in cities and public play and walk areas set up. The efforts to reduce cigarette smoking and harmful use of alcohol should be strengthened.

Research has global impact

The research conducted in Sri Lanka is already having a global impact having been presented and well received at international conferences including the International Union for Health Promotion and Education Conference in Geneva and the Asia-Pacific Academic Consortium for Public Health, said Dr. Steven Allender, explaining that the international interest reflects the understanding of the size of the problem. The work conducted in Sri Lanka is some of the first to begin tackling a difficult problem which will affect 80% of the world’s population by 2050.

The approach to understanding the effect of rapid urbanization applied in Sri Lanka has since informed work in Ethiopia, Peru and India and is likely to be applied in many other low and middle income countries as rapid development occurs, according to him.

When asked whether the findings will be relevant to both developing and developed countries, Dr. Allender said one of the strengths of this research is that the data are collected as developing countries go through the development cycle and the living conditions which cause chronic disease begin to be put in place. These results are important for developed countries because it is not possible to study the impact of urbanization in societies which have been urban in some cases for many hundreds of years.

Results from the study in Sri Lanka provide an opportunity to understand what impact moving current living conditions in urbanized countries, by increasing active transport, altering the types of food available in markets etc., may have on the burden of disease, he said.

The ultimate goal is to provide evidence that will allow governments in countries undergoing rapid urbanization to understand the effects of the rapid development and identify which elements are leading to chronic disease during this process. From this information it is then possible to develop policy responses which reduce the burden of disease associated with rapid urbanization without reducing the other welcome benefits of development for the community, adds Dr. Allender. |