News

How to tackle the sting in the sea

They lurk beneath the waters hugging the coast of Sri Lanka and over the years no one has looked at the impact they have on humans. This scenario has changed this year, for the Toxicology & National Poisons Information Centre based at the National Hospital in Colombo is now looking deep into hospital statistics to create a separate national database on ‘Sea animal envenomation’.

This is a first in Sri Lanka’s medical record-keeping, the Sunday Times learns, and the initial data have been an eye-opener. The data are only from people who have sought treatment at hospitals along the coastal-belt but there could be others including fishermen who resort to home-remedies, it is learnt.

This is a first in Sri Lanka’s medical record-keeping, the Sunday Times learns, and the initial data have been an eye-opener. The data are only from people who have sought treatment at hospitals along the coastal-belt but there could be others including fishermen who resort to home-remedies, it is learnt.

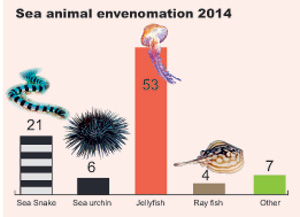

“No deaths have been recorded according to these data,” says the Head of the Centre, Dr. Waruna Gunathilake, pointing out that the ‘National survey of sea animal envenomation – 2014’ recorded stings or bites of jellyfish (lodiya in Sinhala), sea snakes, sea urchins (muhudu ikiriya in Sinhala), ray-fish (maduwa in Sinhala) and unidentified ‘others’.

The “hotbeds” around Sri Lanka seem to be Karainagar, Point Pedro, Kalpitiya, Wellawatte, Panadura and Ambalangoda.

Sea animal envenomation, especially jellyfish stings are not seasonal but seem to occur throughout the year, he says, adding that the distribution of envenomation when taking into account people who had sought treatment, pointed towards Karainagar, Point Pedro, Kalpitiya, Puttalam, Kalubowila, Panadura and Ambalangoda Hospitals.

Zeroing-in on the dangers posed by sea snakes, he points out that someone can die if timely treatment is not taken as the victim could go into muscle breakdown or even kidney failure. “These statistics will be a valuable measuring tool to re-think the way we deal with sea animal envenomation. Earlier we didn’t know the depth of the issue and as such couldn’t streamline even the data-collection,” says Dr. Gunathilake, stressing that the system should be “refined and defined”.

Giving the background, he says that when people became fearful of jellyfish stings at Polhena in Matara, the centre realized that there was no hospital data on sea animal envenomation. Sea animal envenomation was a “hidden entity”.

“If we had proper national statistics then, we could have shown the public that jellyfish stings have been part and parcel of coastal and fishing life and that the jellyfish around the island are not lethal,” he points out. This stimulated them to get hospitals along the coastal-belt to dive deep into past bed-head tickets to fish out the relevant data. The track-back system was carried out at all the main coastal hospitals around the country to get a peek into such incidents in 2014.

Usually, when patients come into hospital, ‘bites’ are identified only in three forms – snake-bites, dog-bites and everything else lumped together as ‘animal-bites’. “Sub-divisions of ‘animal bites’ are essential, whether land or sea to record the extent not only of morbidity (illness) but also whether there is mortality (death),” he urges, adding that Sri Lanka also needs more medical research on sea-snake bites. In Negombo, a few fishermen have been bitten by sea snakes when they attempted to free those that had got entangled in their nets.

There are no hospital records of mishaps due to bello or molluscs, he adds.

| First aid treatment If in case you are stung or bitten, the first-aid and treatment will vary depending on which sea animal it is. There will also be different reactions, with the ‘immediate’ being pain (local), weals, reddening and blistering. There may also be pain spreading through a limb involving regional lymph nodes, agitation, distress and raised heart-rate. Some general rules of first-aid, according to Dr. Gunathilake are:

| |

| When a marine animal bites When marine animals bite or sting, mostly as a defence mechanism, venom could be passed onto the victim through their tentacles, spines or skin, according to Dr. Gunathilake. He says that a majority of such bites or stings could be caused by accidental contact such as stepping on a ray-fish buried in the sand or brushing against a jellyfish while swimming, with divers and fishermen being more vulnerable. Swimmers and snorkelers need to watch for likely interactions with sea animals which live in warm, shallow waters such as rays which have spines on their tails, jellyfish, anemones and corals which have tentacles covered with stingers called nematocysts and sea urchins covered in sharp spines coated with venom.

| |