Columns

Petrie report: Diplomatic blunder projects Sri Lanka as a Rwanda

= UN issues statement against impeachment of CJ while composition of UNHRC changes

It was a week of more challenges for the UPFA Government both in Sri Lanka and abroad. In Colombo, the official process to impeach Chief Justice Shirani Bandaranayake began on Wednesday. The eleven-member Parliamentary Select Committee chaired by Minister Anura Priyadarshana Yapa held its first meeting in Parliament. Standing Orders of Parliament prevent reportage of proceedings of the Committee.

Speaker Chamal Rajapaksa warned all MPs not to discuss matters relating to the PSC outside the House. Warnings have also been issued to the media to heed Standing Orders when reporting. Within one month of last Wednesday’s meeting, the PSC report is required to be presented to the Speaker. However, the Committee is not precluded from seeking extensions.

The next day (Thursday) Chief Justice Bandaranayake received a letter from the PSC to respond to the 14 allegations against her within seven days. She has also been asked to appear before the Committee on November 23, one of her lawyers said yesterday. A team of leading lawyers led by Romesh de Silva will represent her. They were preparing her responses to the charges. These developments came as the impeachment resolution itself caught the attention of the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. From its headquarters in Geneva, Gabriela Knaul, the UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, issued a detailed statement.

Among other matters she noted, “Judges may be dismissed only on serious grounds of misconduct or incompetence, after a procedure that complies with due process and fair trial guarantees and that also provides for an independent review of the decision.” She noted that “the misuse of disciplinary proceedings as a reprisals mechanism against independent judges is unacceptable.” In her view, Knaul said, “the procedure for the removal of judges of the Supreme Court set out in article 107 of the Constitution of Sri Lanka allows the Parliament to exercise considerable control over the judiciary and is therefore incompatible with both the principle of separation of power and article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.”

That the remarks were made when both Colombo and Geneva are yet to reach accord on a date for the visit to Sri Lanka by the UN Human Rights High Commissioner Navi Pillay adds significance. She has been tasked to report to the UN Human Rights Council on the progress Sri Lanka has made in the adoption of provisions of the US-backed resolution passed in March this year.

The situation has been made worse. In almost every crisis faced not only by the UPFA Government, but by Sri Lanka itself, the woeful inadequacy of the External Affairs Ministry (EAM) is highlighted with great clarity. Whatever the rights and wrongs of an impeachment move on the Chief Justice would be, the EAM has failed to set out the Government’s own position to the country’s diplomatic missions abroad. If indeed that has been done, not one country has defended Sri Lanka. The EAM has not been able so far to respond to what this UN Rapporteur; an official, whose pronouncements are taken cognisance of diplomatically by other countries, has commented upon. If that is just one lapse, there is much more. The EAM, as we reveal today, is out of focus. Whilst its officials are busy paying all attention to their Minister, G.L. Peiris’ pet project “Look towards Africa,” things are happening elsewhere.

Last Monday, the UN General Assembly in New York elected by secret ballot 18 member states to serve on the Human Rights Council in Geneva. Contrary to expectations, the United States received 131 votes, Germany 127 and Ireland 124. Others elected are Argentina, Brazil, Cote d’Ivoire, Estonia, Ethiopia, Gabon, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Montenegro, Pakistan, the Republic of Korea (south Korea), Sierra Leone, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela. From the elected countries, Cote d’Ivoire, Estonia, Ethiopia, Ireland, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Montenegro, Sierra Leone, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela are on the HRC for the first time. Whilst United States has been re-elected, Argentina, Brazil, Gabon, Germany, Japan, Pakistan and South Korea served non-consecutive terms.

Besides these countries, continuing as HRC members are Angola, Austria, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Chile, Republic of Congo, Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Italy, Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia, the Maldives, Mauritania, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Qatar, the Republic of Moldova, Romania, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand and Uganda.

China, Russia and Cuba, all three who were close allies of Sri Lanka, will not be members next year. This is at a time when Sri Lanka is expected to face serious issues at the March 2013 sessions in the light of last year’s US-backed resolution. That issues related to the session are receiving Washington’s attention is underscored by the visit to Colombo this week by Alyssa Ayres, Deputy Assistant Secretary in the State Department. She is number two to Robert Blake, who is Assistant Secretary. The only redeeming feature for the Government, however, would be the inclusion of Pakistan as a member this time around.

The EAM focus on “Looking towards Africa” saw the arrival this week in Colombo of the Ugandan President, General Yoveri Kaguta Museveni. When Idi Amin came to power in Uganda in 1971, Museveni fled to exile in Tanzania. There he founded the Front for National Salvation, which helped overthrow Amin in 1979. He ran for President in 1980. When the elections, widely believed to have been rigged, were won by Milton Obote, Museveni formed the National Resistance Movement.

The resistance eventually prevailed, and on January 26, 1986, Museveni declared himself president of Uganda. He was elected to the post on May 9, 1996. He is now on his fourth term. His country, listed by the UN as one of the poorest countries in the world, is a member of the HRC. He and his entourage were given a comprehensive briefing on matters relating to the military campaign to defeat Tiger guerrillas in May 2009. That is not all. The ministers, at their weekly cabinet meeting last Wednesday evening, decided to “grant assistance” to the tune of US$ 1.5 million (about Rs. 195 million) to Uganda. This is for the establishment of Sri Lanka-Uganda Friendship Vocational and Technical Training Centre in Uganda. This is indeed significant for a nation like Sri Lanka which is borrowing a large volume of its financial needs from China, other countries and international agencies to keep the economy going.

Kazakhstan is another country from which Sri Lanka will canvass support. President Mahinda Rajapaksa will pay a two-day official visit to Astana, the country’s capital, beginning Wednesday. He will leave in a special flight. He is also expected to sign an agreement for co-operation in the field of tourism. The cabinet last Wednesday gave approval to the agreement which the government says will “enhance bilateral relationship, strengthen tourism inflow into Sri Lanka and open new avenues for trade and investment.” Diplomatically, Kazakhstan is overseen by the Sri Lanka embassy in Moscow.

A more serious lapse on the part of the EAM was demonstrated when the UN released the report of the Secretary’s General’s “Internal Review Panel on United Nations Action in Sri Lanka” a few days ago. Some parts of the report have been redacted. However, the Sunday Times has seen those redacted parts which not only highlight the contradictions within the UN system but also lays bare that Sir John Holmes, then Under Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs, did not want to use the term “war crimes” when dealing with the Sri Lankan case. Even more importantly, those within the UN system were themselves in doubt about the figure of alleged civilian casualties. There was also confusion about the approach the UN should take.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon receives the Independent Review Panel Report on Sri Lanka from ASG Charles Petrie. UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe

During a visit to Sri Lanka in February 2009, Holmes, a British diplomat, earned the sobriquet “terrorist” from then Prime Minister, Ratnasiri Wickremenayake. Days ahead of the official release of the Charles Petrie panel report the BBC revealed selected parts.

Its report claimed that an Executive Summary had been altogether removed. The report is in two major parts, one (pages 1 to 35 on the inadequacies of the UN system and recommendations for corrective measures) and two on matters relating to the final stages of the war when the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) was militarily defeated.

The Sunday Times has learnt from diplomatic sources that some 29 pages of the report had not been included in the final account, which too, had been released with a few parts blacked out. The question that begs answer is why the EAM did not think it fit, firstly to lodge a protest with the UN Secretary General’s office over the leak. Both the EAM in Colombo and the Sri Lanka Permanent Mission to the UN in New York seemed oblivious to this. Logically such a leak arguably could have only been from the panel’s chief, Petrie, Assistant Secretary General or members of his staff. Secondly, the notion that the report was an “internal document” of the UN and therefore does not concern Sri Lanka does not hold water.

At least as far as Sri Lanka is concerned, it relates to matters which the Government is contesting. Moreover, one would expect the EAM, if not the country’s permanent UN mission which is focused on more mundane issues, to learn that the United Nation’s system has been debating contradictory stances and was sometimes not sure of its own positions. These were highlighted even at a news conference at the UN after the release of the report. Both Petrie and Susan Malcorra, Chef de Cabinet of the UN Secretary General, took part in the news conference. Hence, should not the EAM have seized the opportunity whilst the matter is topical to set out the Government’s case? The fact that there is stoic silence is not only deafening but denies to the Government the opportunity to tell its own story.

Here are some of the parts that have been redacted from the report that was officially released by the UN in New York and seen by the Sunday Times. The blacked out parts are given below in bold italics and include portions which are in the report in normal print for reasons of clarity:

g 26. Three days later, on 12th March, at the UNHQ meeting of the Policy Planning Committee to discuss Sri Lanka several USG (Under Secretary General) participants and the RC (Resident Co-ordinator) did not stand by the casualty numbers, saying that the data were ‘not verified’. Participants in the meeting questioned an OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights) proposal to release a public statement referencing the numbers and possible crimes.

g 38. Progress on accountability was slow, but the UN would continue to pursue the issue. In June 2009 the Policy Committee discussed the possibility of UN action to establish a mechanism for an international investigation, an option presented by OHCHR. Several participants noted the limited support from Member States at the Human Rights Council and suggested the UN advocate instead for a domestic mechanism, although it was recognized that past domestic mechanisms in Sri Lanka had not led to genuine accountability. One participant said that it was important to maintain pressure on the Government with respect to recovery,

g 81. The Policy Committee met two days later, on 12 March, to discuss Sri Lanka. Participants noted variously that this crisis was being somewhat overlooked by the international community, the policy of coordinating a series of high level visits seemed to have produced some positive results, and that the possible involvement of the Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide (SAPG) would not indicate a suspicion of genocide but may add to overcrowding of UN actors involved. Participants acknowledged the apparent need for a Special Envoy but noted this did not seem politically feasible. It was suggested that the Secretary-General’s [public] statements may have appeared a bit soft compared with recent statements on other conflict areas [and it] was suggested [he] cite the estimated number of casualty figures. OHCHR said it would be issuing a “strong” statement which would include indicative casualty figures and raise the issue of possible crimes under international law by both sides.

g Several participants questioned whether it was the right time for such a statement, asked to see the draft before release and suggested it be reviewed by OLA (Office of Legal Affairs). There was a discussion on “balancing” the High Commissioner’s mandate with other UN action in situations requiring the UN to play several different roles. The meeting led to the adoption by the Secretary-General, through the Policy Committee, of several decisions, including: continued engagement on the immediate humanitarian, human rights and political aspects of the situation; system-wide advocacy to press the LTTE to allow safe passage for civilians and UN staff; pressing the Government on protection and assistance to IDPs; inter-ethnic accommodation and reconciliation; political advice to Sri Lanka; child protection; transitional justice; demining; reconstruction; disarmament, demobilization and rehabilitation; political solutions to the underlying causes of the conflict; and renewed efforts to establish an OHCHR field office.

g 83. At today’s Policy Committee meeting, the [RC - Resident Co-ordinator /HC- High Commissioner] as well as [the USG-Humanitarian Affairs] of OCHA underlined the fact that the accuracy of figures remains still quite questionable.

g 84. The next day, after receiving a draft of the statement, the Chef de Cabinet, the USG-Humanitarian Affairs (Note: Reference is to John Holmes, USG) and the RC (Resident Co-ordinator) all wrote to the OHCHR leadership urging that the statement be changed to exclude specific comments for (the High Commissioner’s) consideration, in what is a sensitive situation where the risk of counterproductive reaction from the Sri Lankan government is high (i) As we discussed, we have ourselves avoided being too specific about the casualty figures because of the difficulty of being able to defend them with confidence in the absence of reliable verifiable information…The civilian casualties have certainly been, and continue to be, heavy, but the detailed figures are still to be sure about.

(ii) The reference to possible war crimes will be controversial. I am not sure going into this dimension is helpful, as opposed to more indirect references to the need for accountability, in this conflict elsewhere.

g 150. The sudden end to the conflict prompted additional reflection by the UN on its strategy. A 23 June Policy Committee meeting acknowledged the very limited political space given to the UN in Sri Lanka. Members agreed to: urge the Government to ensure protection and assistance for IDPs in accordance with international law; continue dialogue toward a durable political solution and reconciliation; seek a principled and co-ordinated international approach to relief, rehabilitation, resettlement, political dialogue and reconciliation; and pursue a principle-based engagement by UNHQ and RC/HC/UNCT (UN Country Team), with the Government, International Financial Institutions, and other partners on early recovery. It was agreed that the UNCT would engage with international partners and develop principles of engagement, and a monitoring mechanism to ensure adherence to these principles.

g 152. In the weeks after the end of the conflict, the UN noted heightened intolerance and that “journalists, civil society actors and others have come under physical threat and attack, often labelled “traitors”, for their criticism of the Government’s conduct of the war 137 (Members of the Policy Committee also noted politically, there was little to show for the UN’s engagement with all stakeholders and that the President was not receptive to the Secretary-General’s suggestion to appoint an envoy.) After the Human Rights Council’s adoption of a resolution (see below) considered highly favourable to the Government, enormous posters were placed on advertising panels in Colombo showing the faces of senior Government officials who had defended Sri Lanka at the Human Rights Council.

g 172. By late June 2009, the heads of UN departments and agencies were increasingly focused on accountability, (albeit with considerable disagreement on what action should be taken). OHCHR supported the creation of an international investigation mechanism. But others, noting the limited support from Member States in the wake of the Human Rights Council Special Session, suggested alternatives such as a national peace and reconciliation initiative, a national investigation involving credible international figures or a regionally-led process.

(One participant said that “[i] it was important to maintain pressure on the Government with respect to recovery, reconciliation and returns and not to undermine this focus through unwavering calls for accountability …” OHCHR was tasked with preparation of a UN strategy and position on justice and accountability issues, including the possibility of an international investigation.)

g 173. On the margins of the July 2009 Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) summit in Egypt, the Secretary-General met with President Rajapaksa and urged him “to uphold his commitment to establish an accountability process”.156 On 30 July the Policy Committee met again at UNHQ to address “follow-up on accountability” in Sri Lanka Discussing whether or not the Secretary- General should establish an international Commission of Experts, many participants were reticent to do so without the support of the Government and at a time when Member States were also not supportive. At the same time, participants also acknowledged that a Government-led mechanism was unlikely to seriously address past violations. The Secretary-General said that the Government should be given the political space to develop a domestic mechanism and that only if this did not occur within a limited time frame would the UN look at alternatives. The meeting agreed that the UN would continue to encourage the Government to uphold its commitment to establish a credible national accountability process…..”

The Petrie panel’s origins lay in the three-member “Panel of Experts on accountability in Sri Lanka”. UN Secretary General Ban Ki moon appointed this committee to advise him “on accountability” during the final stages of the separatist war. In April last year this panel handed in it report. The panel members said in an accompanying memorandum to their report that while “many UN staff had distinguished themselves during the final stages of the conflict, some agencies and individuals had failed in their mandates to protect people, had under reported Government violations, and suppressed reporting efforts by their field staff.’ It added that the UN “did not adequately invoke principles of human rights that are the foundation of the UN but appeared instead to do what was necessary to avoid confrontation with the government.”

Thereafter, Petrie with a three member staff was tasked with “(i) providing an overview and assessment of UN actions during the final stages of the war in Sri Lanka and its aftermath, particularly regarding the implementation of its humanitarian and protection mandates; (ii) assessing the contribution and effectiveness of the UN system in responding to the escalating fighting and in supporting the Secretary-General’s political engagement; (iii) identifying institutional and structural strengths and weaknesses, and providing recommendations for the UN and its Member States in dealing with similar situations; and (iv) making recommendations on UN policies or guidelines pertaining to protection and humanitarian responsibilities, and on strengthening the system of UN Country Teams (UNCTs) and the capacity of the UN as a whole to respond effectively to similar situations of escalated conflict…”

That the Internal Review Panel’s 128-page report was made public at a time when the UN was taking strong criticism over the internal strife in Syria in particular is of interest. The report drew considerable western media attention. In Syria, the government of President Bashar al-Assad stands accused of using excessive force to crush an internal uprising. The panel has concluded that “the UN’s failure to adequately respond to events like those that occurred in Sri Lanka should not happen again. When confronted by similar situations, the UN must be able to meet a much higher standard in fulfilling its protection and humanitarian responsibilities.”

The Petrie panel has made five main recommendations. In calling for a renewed vision of the United Nations, the report observes “the Secretary-General should renew a vision of the UN’s most fundamental responsibilities regarding large-scale violations of international human rights and humanitarian law in crisis, with a particular responsibility of senior staff.”

Why did not the Minister or EAM officials summon a news conference and assert Sri Lanka’s position that no “large scale” violations of “human rights and humanitarian laws,” had taken place, asked a retired senior Sri Lankan diplomat and former Foreign Ministry official. He pointed out that the Petrie report reveals that there has been a debate within the UN itself on whether the issue was “large scale.” Another is the five recommendations made by the panel to “improve United Nations engagement with Member States and build political support.”

One of them says, “The Secretary-General should use the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) as a ‘convening’ initiative to invite Member States to receive and consider information on the human rights aspects of a relevant crisis situation; and in this regard, DPA (Department of Political Affairs) and OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights) should be jointly tasked with managing its use and fulfilling the Secretariat’s own responsibilities under the concept.” The R2P doctrine, according to the UN, was “initially given a voice by leaders in the human rights community in 2001, is the enabling principle that first obligates individual states and then the international community to prevent and end unconscionable acts of violence irrespective of where those acts occur. R2P was universally endorsed at the 2005 World Summit and then re-affirmed in 2006 by the U.N. Security Council.” That the Sri Lankan example has been taken to justify right to intervention in one country by one or more others has not made those at the EAM open their eyes, to say the least, is highly damning,” the diplomat who spoke on grounds of anonymity said.

At the news conference at the UN headquarters in New York, Chef de Cabinet Malcorra admitted that the report has been redacted.

According to her, “there was a decision taken after a discussion with the Secretary-General regarding how is it that we are going to make this report public. The report has references to documents related particularly to the policy committee meetings and the deliberations, but also to some of the code cables that are of a strictly confidential nature. The Secretary-General felt, and I fully share his view, that there was nothing that will change the transparency to show the report if we took out those aspects that have a clear relation to documents of internal use that were fully available to the Panel,……………, but also put the Organisation at risk by sharing publicly in such a short term internal documents…..”

Question: I wanted to ask you about the redactions. As you probably know, the way it was put up, it was possible to see behind the redactions and, therefore, if I can, in paragraph 173, (PLEASE SEE ABOVE) what was taken out was a direct quote from the Secretary-General, not about staff members, him saying the Secretary-General said that “the Government should be given the political space to develop a domestic mechanism.” That’s why I’m asking you, do you think that that mechanism has come to anything? Another redaction has Mr. Holmes saying that we shouldn’t call it a war crime, and it’s taken out. That doesn’t seem to be about safety. It really does seem to be just what you said about kind of self-serving. So, I’ve seen the executive summary as well, and it seems it’s nothing about staff safety. It’s just a harder hitting version. Why did you take it out?

Malcorra: Because I used two arguments and you took only one. I said to you that there were two issues. One was documents of internal purview that were strictly confidential. I said that was the first issue and the second one was staff safety.

Petrie: In the redaction between the penultimate version and the final version actually there was no substantive difference in terms of facts and even argument. What we were trying to do is to find language that would make the report more balanced and more acceptable in terms of the message that we were trying to give.

Needless to say that the answers at the news conference reveal more than what both Malcorra and Petrie wanted to hide. The first country to react to the Petrie panel report was Canada. Interesting enough that some of the inadequacies highlighted in the report fall on the shoulders of a Canadian diplomat, Neil Buhne who was the UN’s Resident Co-ordinator in Sri Lanka. This is what the Canadian Foreign Minister John Baird said in Ottawa on Friday: “The Prime Minister and I take every opportunity to raise Canada’s concerns with respect to the need for progress on reconciliation, accountability and respect for human rights in Sri Lanka. Canada calls on the Sri Lankan government to finally put the people of that country first. Canada also notes the Secretary General’s comments and will work with the international community to ensure mistakes made in Sri Lanka are not repeated.”

As thsese developments show, the gross intransigence of the External Affairs Ministry albeit its Minister G.L. Peiris has denied to both the government and for the country the opportunity to tell their most important story. The United Nations has said its and that has raised more questions than answers.

Furthermore, if the Petrie report seems to lament Sri Lanka’s diplomatic success in 2009 in preventing UN intervention in Sri Lanka through the Security Council, the Government’s failure to invest the military achievement in an all-inclusive political process, especially through the LLRC report, is what is pitiful. Now Sri Lanka will figure in various UN committee debates, studies and seminars within and outside the UN system. The Petrie report will become an important input to the UNHRC sessions in Geneva and Sri Lanka will be a case study for diplomatic training programmes in many countries as it will be considered the first major UN failure in a war situation. Sri Lanka will be seen as another Rwanda in world eyes. What an indictment! Having prevented UN intervention diplomatically, what a crowning glory in a post-conflict context for the Rajapaksa Government.

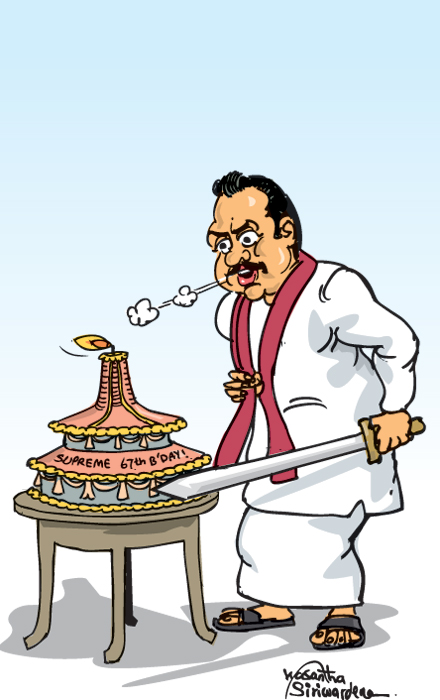

Its time President Rajapksa takes a close look at the developing situation and prevents any further irreparable damage.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus