News

More pay for higher plucking output sticking point in tea worker wage tussle

It all started in 2014, when plantation workers demanded that the basic daily wage be raised to Rs 1,000.

At that time the exchange rate of the US dollar was Rs 130. Five years later, it trades above Rs 185.

Then, a leading trade union held a ‘Satyagraha’ protest at Malliyappu junction in Hatton on July 7, 2015 led by late leader of the Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC), Arumugam Thondaman, and his supporters at midnight ahead of the signing of the collective agreement with unions and Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs).

Since the death of Mr Thondaman last year and many unfulfilled promises by government ministers along with a Cabinet approval for a wage increase, nothing has materialized.

And it has been a year since the incumbent government pledged to raise the basic wage.

A new round of tripartite talks began last month between trade unions and RPCs. The Ministry of Labour is an observer.

The 2018 collective agreement for two years, increased the basic daily wage to Rs 700. That agreement will lapse in March.

The second round of talks scheduled for Thursday were called off after some of the trade unionists were asked to self-quarantine after being exposed to a coronavirus infected individual.

Talks will resume on January 7.

All three plantation worker trade unions, the Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC), Lanka Jathika Estate Workers Union (LJEWU), and Joint Plantation Trade Union Centre (JPTUC) are vehemently opposed to a wage less than Rs 1,000 a day.

S. Ramanathan, the general secretary of JPTUC, a collective of 10 unions representing thousands of workers in the central hills, refused to sign the previous collective wage agreement on the basis that allowances for workers were curtailed.

He is among those taking part in the latest talks.

“It was a reasonable wage increase demand, considering the [rising] cost of living,” secretary Ramanathan said, while reiterating that unions will not accept a lower wage.

The acute shortage of workers in estates, the increasing migration of plantation youths to cities looking for employment, and mismanagement of tea estate companies, raised questions on the future of the industry, Mr Ramanathan added.

“If the plantation companies can hire a worker at Rs 1,000 per day with a midday meal and transport to work in an estate, why can’t they pay the same to the workers as well?” Mr Ramanathan asked, while stressing that many youths prefer doing manual labour rather than being employed by a tea plantation company.

Lanka Jathika Estate Workers Union (LJEWU), a United National Party (UNP) affiliated union, asked why the companies were being summoned to discuss the incentive allowances when it was about the increase of the basic wage as the government has declared.

Vadivel Suresh, the general secretary, who joined the talks, told the Sunday Times that the ‘politically promised’ wage increase is being downplayed by companies with new proposals to increase the workload of workers.

According to the new proposal, workers will have to pluck 20 kilos compared with the current 18 to be eligible for allowances, and the number of days they report to work.

The trade unions also stressed that the statutory 15% allocation for Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) and Employees’ Trust Fund (ETF) based on their daily wage should not be included when revising the wage.

A CWC source who took part in the talks also said it is opposed to new incentives proposed by the companies which are detrimental to worker benefits.

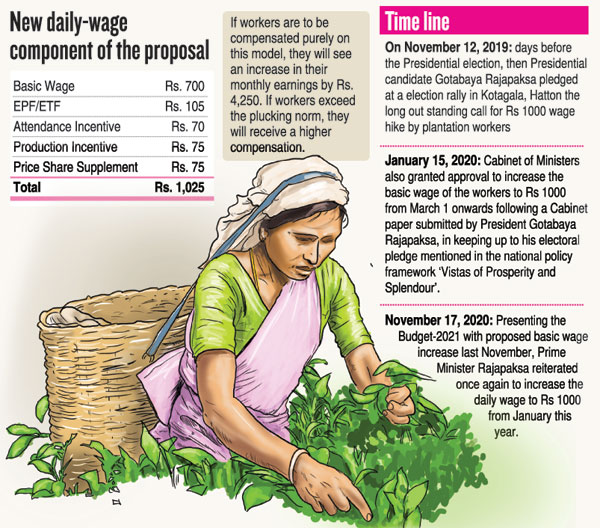

On November 12, days before the presidential election, then-candidate Gotabaya Rajapaksa pledged at an election rally in Kotagala, Hatton that the longstanding demand by plantation workers for a Rs 1,000 wage will be delivered when he takes office.

Last January, the Cabinet approved the increase in the basic wage to Rs 1,000 from March 1.

The Cabinet paper was submitted by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, in keeping with the elections pledge in his national policy framework, ‘Vistas of Prosperity and Splendour.’

Later, his office reiterated the need to increase the minimum daily wage of estate workers since the government has taken several initiatives such as tax exemption and fertiliser subsidy.

Presenting the Budget-2021 with a proposed basic wage increase last November, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa reiterated that the daily wage will be raised to Rs 1,000 from this month.

He also stressed mismanagement where companies have failed to pay taxes even though the government continues to provide basic facilities such as hospitals, schools, houses, roads, electricity, and water.

“Under these circumstances, steps will have to be taken to encourage plantation companies that have become more successful and to review the privatisation agreements of unsatisfactory plantation companies and to setup alternative investments that can be commercially developed. I intend to present to Parliament in January a legal framework that will change the management agreements of plantation companies that are unable to pay this salary and provide opportunities for companies with successful business plans,” Mahinda Rajapaksa said in his budget speech in November.

The average prices at the Colombo tea auctions have increased compared with last year. The average price in November (2020) was Rs 641.66 compared with Rs 596.67 in November (2019).

Mr Ramanthan recalled a position taken by RPCs during previous wage talks where companies held that the basic wage could be increased up to Rs 1,000 if only tea prices went up to Rs 738.

“If we go with that same logic, by that time [2018], tea prices were Rs 594, therefore they should have offered workers Rs 804 as basic wage, but they did not. Now, when the tea price is at Rs 629.94, they can comfortably agree for Rs 853, but they are not willing to do so,” Mr Ramanathan stressed.

Meanwhile, small-scale tea plantations have become a success story with significant contribution to exports over the years as large-scale Regional Plantation Companies only contribute nearly 25 percent, according to data from the Treasury.

Ahead of the next round of talks, the RPCs proposed a hybrid mechanism of a daily wage model and the productivity-linked earnings system, similar to the smallholder sector arguing it can be implemented with great success.

The RPCs proposed through the Planters’ Association of Ceylon, that a fixed daily wage will be offered with the re-introduction of attendance and productivity incentives.

The proposed mechanism is a mix of three days of daily wage and three days of productivity-based earnings.

The first alternative under the productivity-linked proposal is a system where workers are paid Rs. 50 for every kilo of green tea leaf plucked (inclusive of EPF/ETF), the planters body said, indicating workers have the potential to earn more.

Under the new daily-wage component of the proposal, workers will be paid Rs. 1,025 for a day’s work including EPF and ETF.

The breakdown is as follows: basic wage – Rs. 700, EPF/ETF – Rs. 105, attendance incentive – Rs. 70, production incentive – Rs. 75 and price share supplement – Rs. 75.

However, most of the plantation companies are of the view that if the trade unions agree with their proposals, they would abandon the collective agreement and approach the Wages Board to finalise the basic wage with workers directly.

Hayleys Plantations Managing Director Roshan Rajadurai told the Sunday Times that companies could not meet the trade unions’ wage hike demand since they were also going through a crisis, with oversupply of tea in the global market due to the pandemic.

“We have already informed the Prime Minister and the Presidential Secretary of our position on why we cannot implement this wage hike. If there is no agreement reached at talks, we will go to the Wages Board directly with the proposals so the workers can choose a wage model on their own,” Dr Rajadurai said.

Responding to the allegations by unions that the proposed models would put more workload on the workers, Dr Rajadurai said that on average Sri Lankan tea pluckers pluck 30-35 kg of tea a day and the proposed models were designed in a way to enable workers to earn more than Rs 1000 depending on their capability.

P Muthulingam, director at the Institute of Social Development (ISD), a non governmental organisation based in Kandy that focuses on policy research in the plantation community, said companies are trying to keep the profit margin high by increasing the workload.

“Plantation companies also don’t reinvest in the estates by re-planting crops as they used to decades ago. They totally depend on the government fertiliser subsidy and other benefits. How can the workers bring in 20 kilos [a day]?” Mr Muthulingam asked.

For most plantation workers, a basic wage of Rs 1,000 per day remains a long shot.

Arulappan Idayadevi, 41, a mother of three from Bogawantalawa estate lower division, feeding the family with the wages of two people has become increasingly difficult, more so following the coronavirus epidemic’s economic devastation.

“Even Rs 1,000 as a basic wage is not enough for a family. Prices of rice and coconut went up recently forcing us to reduce meals for our children. We feel, we got cheated by these empty promises for years. We just need the wage increase for our survival,” said Ms Idayadevi, who is part of a workers led collective called Plantation Workers’ Rights Movement advocating a decent wage.