News

From ‘dark ages’ to conservation: Evolution of Zoos

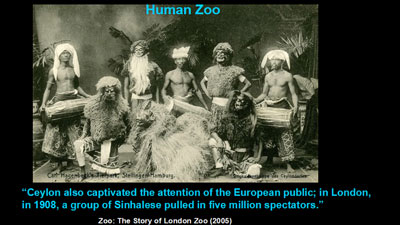

Human Zoo – Ceylon captures European attention (Courtesy Prof. Jayawickrama’s presentation)

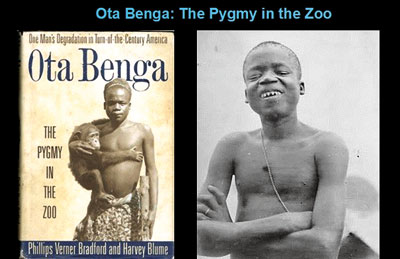

Stark are the images portraying the dregs to which humanity can sink — diminutive pygmy Ota Benga from the Congo being “displayed” for gawking crowds in the New York Zoological Gardens, Bronx, in the United States of America (USA).

While many are aware of this shocking aberration in the name of ‘ethnological exhibits’ in 1906, not so long ago, most may not know that among the “human exhibits” paraded around the world were also a group of drummers and dancers from Sri Lanka.

It is Ota Benga’s story that environmental expert Prof. Lalith Jayawickrama, Professor of Environment Science and Nutrition, Department of Natural Sciences, University of Dubuque, Iowa, US, lifts up from its murky dregs to highlight the “lowest point” to which zoos could sink, before stressing the invaluable role played by zoos currently.

And this important role that a zoo could play was also the vision of Lyn de Alwis, in whose memory the first-ever Lecture titled ‘The role of modern zoos in education and wildlife conservation’ was delivered by Prof. Jayawickrema on Friday evening at the auditorium of the Sri Lanka Foundation Institute, Colombo 7. The Memorial Lecture was organised by Lanka Nature Conservationists and the Lyn de Alwis Memorial Wildlife Trust.

Who better than Prof. Jayawickrama to deliver this lecture, for he had known Lyn de Alwis, “a celebrated Director of the National Zoological Gardens, Dehiwela” from the time he (Lalith) was a toddler and learnt his early lessons on the environment from this visionary. When Lyn de Alwis established the Young Zoologists’ Association (YZA) in the early 1970s, Prof. Jayawickrama was right there, being enrolled as one of its members.

“Sustainable zoos are the need of modern times, for they have a vital role to play in the aspects of ‘Conservation and re-introduction’ and ‘Environmental education’ while ‘Entertainment’ comes last,” says Prof. Jayawickrama, recalling how Lyn de Alwis was ahead of his times. He launched the March for Conservation — a powerful lobby for the protection of the environment being destroyed by the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Programme — born in the late 1970s within the National Zoological Gardens in Dehiwela which was then headed by Lyn de Alwis and the YZA was for environmental education.

Prof. Lalith Jayawickrama in Colombo. Pic by Indika Handuwala

When the Sunday Times meets up with Prof. Jayawickrama a day before he delivers the Memorial Lecture, he reiterates that what is missing in most modern zoos is ‘re-introduction’ of endangered species into the wild after evidence-based scientific conservation research which could be conducted either ‘in-situ’ – doing research at the zoo itself — or ‘ex-situ’ – doing research outside the zoo.

Referring to significant conservation carried out by the National Zoo in Washington DC, part of the Smithsonian Institution, he cites several examples, one in which he himself had been involved. They are:

n The highly endangered golden lion tamarin (golden marmoset), a monkey in the South American Amazonian forests. The National Zoo took the leadership in research and raised a family of golden marmosets, while conducting genetic studies to make sure they had the right genetic pool. Trained how to look for food, this family was later taken to Brazil, habituated with the wild ones and then released into the wild.

* He has been personally involved in the research and conservation at the National Zoo of the desert tortoise of Las Vegas, Nevada. With the loss of the unique habitat of Las Vegas to the glitter and glamour of casinos, the desert tortoise was endangered and highly threatened and research on various types of diets suitable for it was conducted, with Prof. Jayawickrama analyzing what they ate, to help determine what they should be fed while being raised in captivity. (Incidentally, in the ongoing Smithsonian Primate Research Project being conducted at Polonnnaruwa by Dr. Wolf Dittus, the nutritional analysis was done by Prof. Jayawickrama.)

* With bison in the prairies of Iowa being slaughtered, gradually it had been noticed that the prairies were dying. This was because the bison were very much a part of the eco-system there, for they kept the grasses down by feeding on them and also passing out the seeds after digestion which led to the re-generation of the prairies. Many zoos linked up to conduct genetic studies, using technologies for artificial insemination etc., to raise a big population of bison which were then released back into the wild.

* The American wolf has been portrayed as ‘big and bad’, from the time of the tale of Red Riding Hood. Being hunted down ruthlessly in their very domain, the Yellowstone National Park, it took a while for the authorities to realize that the National Park itself was dying. The reason was simple – the ecological balance had gone awry. With the wolf out of the picture, its prey — the elk population — was proliferating chomping up all the plants, making the invaluable willow and aspen to dwindle. The beavers in the streams flowing through this National Park were left without wood to perform their stream-damming activities. In its wake, came flooding of the National Park which destroyed other fauna and flora.

Realizing the important role played by wolves, the authorities re-introduced a small pack of wolves, amidst vociferous protests by the farmer-lobby which even went to the extent of killing the wolves and hanging their skins on fences. But with the re-introduction of the predator-wolves, the elk population which had gone back to its defensive behaviour, munching on the plants but at the same time attentive to any lurking dangers, led to the National Park being saved from the brink of extinction. The authorities also educated the farmers to see the bigger picture – even if it meant losing one or two sheep to the wolves, as against saving the Yellowstone National Park itself!

Amidst the rejoicing over such projects, Prof. Jayawickrama, however, issues a word of caution, citing other examples where things have gone in a different direction. Many zoos conducted research, conservation and re-introduction of the American alligator which was endangered earlier, to Florida. But now these alligators have become a menace and licences are being issued to hunt them down, as a culling measure to keep the numbers down.

Lamenting the rapid loss of the natural environment, he says that modern zoos are now acting as repositories of exotic species. The Pere David’s deer (milu or elaphure), native to Mongolia, has no members living in the wild and are found only in zoos. When the National Zoo in Washington wanted to re-introduce them into the wild, it found that the deer’s natural environment was gone.

“So the last-stop for endangered species is the zoo,” says Prof. Jayawickrama, adding that the one and only Tasmanian wolf died in the zoo. The ‘ideal’ is to raise such species and re-introduce them into the wild. But the natural habitat should be there. The natural habitat is being lost faster than such re-introductions can take place. Zoos are also a good education tool for children on conservation, who will then take the message home to their parents that the old ways of destroying the natural habitat is wrong. “We still have time. It’s not too far gone yet. If we don’t look after our environment, we will need bigger and better zoos.”

This is why, the Sunday Times learns, that some zoos, such as those in San Diego and Los Angeles, have embarked on the ambitious approach of the ‘frozen zoo’ concept where tissues, embryos and eggs of highly vulnerable species are being preserved thus.

Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo (Courtesy Prof. Jayawickrama’s presentation)

Earlier, Prof. Jayawickrama leads us down the corridors of time to the 16th century, with the origins of the zoos being “menageries” (Oxford Dictionary: A collection of wild animals kept in captivity for exhibition; while the French had described it as an “establishment of luxury and curiosity”) or an assembly of animals to entertain the aristocrats. They were formed as an extension of colonial power, with exotic species of animals and plants being collected from the occupied countries and considered ‘prized’ possessions, be they living or even dead. Even the museums as well as the circuses which exhibited not only monster-like animals but also men, women and children including Ota Benga from the Congo (who committed suicide after being released into a community living in Virginia), the drummers and dancers from south Ceylon, an Eskimo Inuit family and more from India and Africa, were part of this network.

While Ota Benga had been traded by Dr. Samuel P. Verner, another name oft mentioned with animal dealing and human trading was John Hagenbeck. His brother, Carl, an animal trainer who supplied animals to the zoos of Berlin and then Hamburg, Prof. Jayawickrama points out, also set up shop in the US in 1883 and founded a circus in 1887. Carl had exported 700 leopards, 300 elephants and much more in shiploads to menageries.

And these brothers two, John and Carl, were also inextricably linked to then Ceylon, for an internet search done earlier by the Sunday Times revealed that the Ceylon Zoological Gardens Company in Dehiwela was theirs. When they went bankrupt in 1936, the colonial government of Ceylon had acquired it. The Hagenbecks had used the area as a collecting depot for captured wild animals to be sent to European zoos.

By the 17th century, however, the rumblings against such heartless activity in menageries and travelling circuses had begun in France, with strident calls in the early 18th century that it was not right to have private menageries and the masses should have access to them, bringing in their wake the opening up of zoos to the public.