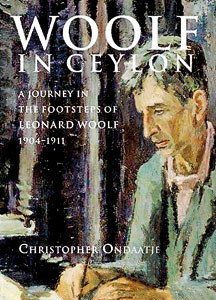

The seminar opened with a series of projected photographs including a portrait of Leonard Woolf painted by Henry Lamb in 1912 when Woolf was 32 as well as several illustrations from ‘Growing’, Woolf’s autobiographical memoir of his seven years in Ceylon, plus a number of photographs from the collection of Sir Christopher Ondaatje, used in his book, ‘Woolf in Ceylon’, and kindly lent by the author.

The photographs provoked discussion on the sensibility and values with which Woolf arrived in Sri Lanka and the extent to which he can be called an imperialist, or indeed an anti-imperialist. The distinction was drawn between racism and imperialism, and it was agreed that Woolf was certainly not racist, due perhaps to his own Jewish background. He was described as “a very specific individual in a very specific set of circumstances”, and it was suggested that it was necessary to beware of generalisations about his cultural attitudes, which were essentially contextual.

|

Jan Kostowski pointed out that Woolf was a working civil servant, as well as a Jew, and as such “a loner in a prestigious position”. It was notable for example, as explained in his autobiography, that on his first posting to Jaffna, Woolf spent most of his time with his 40 volumes of Voltaire and his fox terrier, thereby avoiding the “execrable” society of his British fellow-residents. One of the photographs in ‘Growing’ shows Woolf with his two favourite dogs. Mr. Sivasambu raised the subject of Woolf’s lifelong attachment to dogs which he found anomalous. Dr. Jane Russell, on the other hand, found it completely normal for Woolf to be so fond of dogs. She mentioned that Woolf had taken his fox terrier with him to Jaffna all the way from England, and that his love of dogs merely exemplified his Englishness.

Another illustration shown was a painting of a Sri Lankan religious festival from the early 20th century. Mr. Sivasambu noted that Woolf had been in charge of both the Kataragama Festival while AGA Hambantota, as well as the Kandy Perahera during his posting to Kandy. He queried Woolf’s use of the word “tom toms” to describe Sri Lankan drums. Rohan de Saram spoke about the different kinds of drums depicted in the scene and others in the audience commented that Woolf, although not an imperialist by nature, nonetheless unquestioningly used the language of the imperial context in which he found himself. As Dr. Russell noted, Woolf was not an orientalist: on the contrary, he was steeped in western culture, in Greek and Roman civilisation, and therefore he had no special interest in Sri Lankan culture.

Ian Griffiths of the Virginia Woolf Society also spoke of Woolf’s “intellectual remoteness” from Sri Lankan culture which he attributed to his “Cambridge education”. He suggested that Woolf had a different aesthetic which meant he did not appreciate the subtleties of Sri Lankan drumming nor the sculptures of the Hindu temples, describing them in ‘Growing’ as “florid”. However, the extent to which this lack of understanding can be described as ‘imperialist’ is debatable. He said Woolf‘s idea that the British colonial government should compensate Sri Lankan farmers for the loss of their cattle from rinderpest in 1910 was considered radically “socialist” at the time. Woolf could therefore be described as a “benevolent or caring imperialist”.

Madame Micha Venaille, Woolf’s French translator, took up this point. She said that Woolf was both “generous and intelligent”. Woolf talked to the village people who were deprived of language because they were deprived of power. He listened to them and reproduced their thoughts and ideas in his book, ‘Village in the Jungle’. In this way, he gave a voice to the voiceless. She maintained that he continued with this later on when he engaged with the slum dwellers of Manchester in the 1930’s. She said, “He sat under a kumbuk tree and talked to the villagers: he listened to them and later he talked to women in the slums of Manchester. He had an empathy with people who were different from him. He was not a snob in the sense of class – he could talk to and listen to anybody. His empathy with the ordinary people was very anti-Cambridge... it was outside his own class.” Others suggested that this was possibly linked to his self-effacing demeanour and to his Jewishness.

Woolf’s enduring trait of self-effacement was discussed by Ian Griffiths in relation to Woolf’s relationship with his first wife, the novelist Virginia Woolf (nee Stephen). He agreed with Jane Russell that this had been a platonic relationship based on an artistic venture which was centred on the writing of Virginia’s many novels as well as other publications associated with their publishing house, the Hogarth Press. (This included the works of Freud in English).

Griffiths said, “Virginia was sexually abused as a child by a young relative and this left her very highly strung. Woolf was a methodical man and he became the spine of Virginia Woolf’s novels: he organised her days and nights so she could write. It is heretical – the (Virginia Woolf) Society won’t like me saying it - but without Leonard Woolf, there would have been no Virginia and without Virginia Woolf, there would have been a great loss to 20th century literature.”

Jan Kostowski took up this point. Woolf, he argued, had a history of supporting vulnerable outsiders, whether they were the villagers of jungle hamlets in Hambantota district or the out-of-control Virginia. “Woolf,” he stated, “was a great humanist but it is difficult to relate to the extent of his humanism unless you know Sri Lanka.”

Finally, Nathan Sivasambu summed up Leonard Woolf’s contribution when he says in his paper “that Woolf was and remained of the Cambridge enlightenment whose values were those of rationality and humanism”. |