Disasters have been a favourite element of story tellers over millennia – and we science fiction writers have used more than our fair share, sometimes involving calamities beyond our home planet.

In my own novels and short stories, I have imagined many and varied disasters that happen at the most inconvenient moments, just when everything is going according to plan. A tsunami arrives towards the end of the story in Childhood’s End (1953). In The Ghost from the Grand Banks (1990), an ambitious plan to raise the Titanic is wrecked by a massive storm in the north Atlantic. And The Songs of Distant Earth (1986) suggested a planetary rescue plan for the ultimate disaster: the end of the world when our Sun explodes.

|

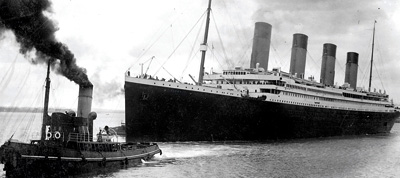

| The Titanic leaving Southampton on her ill-fated voyage on April 10, 1912. AFP |

In real life, however, I have been enormously lucky not to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when Nature unleashes her fury, or humans bungle matters on their own.

But two tragedies that happened 92 years apart have left deep impressions in my mind: they illustrate how communications failures can compound the impact of a disaster.

I was born five years after the biggest maritime disaster the world had known: the sinking of the ‘unsinkable’ HMS Titanic while on her maiden voyage. My home town Minehead, in Somerset, was not more than a couple of hundred kilometres from Southampton, from where the Titanic set off. All my life, I have been intrigued by the Titanic disaster.

I have been particularly interested in what happened to the Titanic’s distress call after she hit the iceberg at 11.40 pm on the night of 14 April 1912. When Captain Smith gave the order to radio for help, first wireless (radio) operator Jack Phillips used the Morse Code to send out "CQD" six times, followed by the Titanic call letters, "MGY".

It was the second wireless operator, Harold Bride, who suggested half-jokingly, "Send SOS -- it's the new call, and this may be your last chance to send it." Phillips, who perished in the disaster, then began to intersperse SOS with the traditional CQD call.

Responses to this distress call came too late to save the ship’s 1,500 passengers and crew who perished. A series of unfortunate factors compounded the disaster. The most ironic among them was that the wireless operator on the Californian, located closest to the Titanic, had shut down for the day just 30 minutes before the first distress call was sent out. Had the Californian been listening, it could have responded hours before the Carpathia, the eventual rescue vessel.

Official enquiries into the disaster revealed that the wireless operators on the Titanic had, in fact, received alerts from other ships about massive icebergs in the vicinity. But the operators, overworked transmitting private messages of the ship’s wealthy passengers, failed to pass that vital information on to the bridge.

The Titanic disaster prompted the shipping community to introduce a 24-hour radio watch on all ships at sea. It also consolidated the role of maritime radio in distress signalling and rescue operations. We can only guess how many thousands of lives at risk have since been saved thanks to timely warnings or distress calls.

|

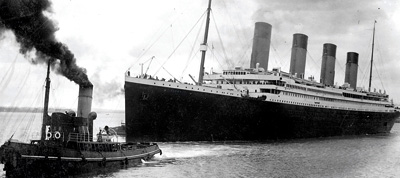

| Tsunami 2004: An aerial view of the destruction in Kalmunai |

But the absence of a timely warning once again characterised the second disaster to touch my life. Arriving 10 days after my 87th birthday, the Asian Tsunami of December 2004 left a massive trail of destruction in my adopted country Sri Lanka and several other countries bordering the Indian Ocean.

Astonishingly, a full century after the invention of radio, the Tsunami arrived without any public warning.

The disaster’s death toll could have been drastically reduced if its occurrence -- already known to scientists -- was disseminated quickly and effectively to millions of coastal dwellers living on its predictable path. Even a half hour’s notice would have allowed people to run away from the coast, and in many affected locations there was just enough time to get to safety. But alas, that didn’t happen -- and tens of thousands perished.

What happened, how and why has been analysed repeatedly since then. It is now known that the failures were human, not technological. To ensure better results next time, we need to achieve an optimum mix of technology, management systems and community preparedness -- not just for tsunamis, but for many other hazards that we live with. We have to remember that delivering credible early warnings to those who are most at risk is both an art and a science.

The tsunami also reminded us how disasters can make our information society vulnerable. When electricity and telephone services -- both fixed and mobile – went down in the worst affected areas, a century old technology came to the rescue: amateur radio enthusiasts restored the first communication links with the outside world, sometimes using the Morse Code to economise the power of car batteries.

Courageous and resourceful ‘radio hams’ were at the forefront of relief efforts in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India, and Hambantota in Sri Lanka.

In those early hours and days, Marconi’s faithful followers helped save lives and allowed a rapid appraisal of damage. As the President of the Radio Society of Sri Lanka remarked, “When all else is dead, short wave is alive.”

Communicating disasters -- before, during and after they happen -- is fraught with many challenges. Today’s information and communication technology (ICT) tools enable us to be smart and strategic in gathering and disseminating information. But there is no silver bullet that can fix everything. We must never forget how even high tech (and high cost) solutions can fail at critical moments. We can, however, contain these risks by addressing the cultural, sociological and human dimensions.

The lessons of history are clear: if we are not careful, we can easily lull ourselves into the same kind of false confidence that doomed the Titanic. |