‘Bad boy’ of Lankan lit is no more

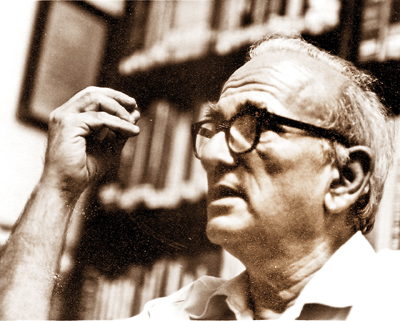

Carl Muller (file photo). Pic by Shehani Fernando from the Sunday Times Mirror Magazine of June 8, 1997

Having spent the last chapter of his life in his eyrie up in Kandy, ensconced in his beloved den of books, Carl Muller, the literary enfant terrible of Sri Lanka, is no more.

On December 2, the first Sri Lankan to be internationally published breathed his last, surrounded by family.

With gimlet eyes behind horn-rimmed glasses Carl delighted in kicking the hornet’s nest with his novels depicting uproariously salacious Burghers. (“There are skeletons in every cupboard. It’s not fair for me to rattle these skeletons about, but if they make a damn good story then why not?”). To the end he would be a pugnacious fighter with a dry wit.

But he was at the same time a devoted family man- and losing his son Destry in 2001 aged 21 dealt a blow he would never recover from. Carl would bring forth a collection of Destry’s poems which would win a State Literary Award posthumously- an award he himself won for the historical novel Children of the Lion.

Once I would meet a younger relative who sadly shook his head over ‘Uncle Carl’. “It was rather too bold” was the gist of his take on the oeuvre which exposed a hilarious, incestuous, licentious clan- the railway Burghers who – other relatives irately claimed- were really very respectable. But Carl, coming from a family of 13 children, always maintained that a lot of Burgher life remained unspoken amidst the breudher, the bolo fiado, the love cake and the milk wine- and the von Bloss saga in truth was a hyperbole of that darker vein.

Carl would point out also that he also showed how “while the other buggers are throwing bombs at each other, we Burghers are getting on without any problems… All I did was celebrate Burgher life”.

Carl Muller the literary Goliath is best known for the Burgher saga- the Jam Fruit Tree trilogy, the first of which won the Gratiaen in 1993. Two separate von Bloss novels and historical novels followed, while he also produced poetry, short stories, and children’s books and even consulted his crystal ball, writing the science fiction novel- Exodus 2300.

Carl like his Carloboy von Bloss of the Burgher novels was expelled from three schools before entering Royal College and drifted to the Royal Ceylon Navy, the Ceylon Army and then the Port of Colombo as a pilot station signalman.

Through his Burgher saga, Muller wove into English literature a fresh voice- the rhythm of Sri Lankan English at its most native- though somewhat caricatured- a distinct leap from characters who spoke as if they had stepped out of a Jane Austen drawing room.

In 1992, the year of the Jam Fruit Tree, this diction fresh in print came as a great revelation to a young boy called Shehan Karunatilaka–who would later go on to win the Gratiaen award himself–so, “literature didn’t have to be aristocratic and elegant. It could be mad, bad and filthy. Who knew?”

Certainly Muller would light the way for so much later genius in Sri Lankan writing.

His own literary avatar was Carloboy, a young ‘Amden’ if ever there was one- whose misadventures endeared him to countless readers- an autobiographical renegade braving the high seas of adulthood. He also worked in advertising and travel, and was a journalist in the Middle East and Sri Lanka.

When The National Institute of Fundamental Studies named three newly identified goblin spiders after famous authors, Carl was the only resident writer- alongside Michael Ondaatje and Shyam Selvadurai so honoured. Brignolia carlmulleri must be the most enduring ode paid him.

Carl is survived by wife Sortain (née Harris), and children Ronnie, Michelle, Minette and Jeremy and grandchildren. In his later years, he battled dementia and was cared for devotedly by his family.

| The tribe remembers | |

| Some literary figures reminisce on Carl the rebel and literary trailblazer. Prof. Walter Perera: Carl Muller’s The Jam Fruit Tree which was declared the joint winner of the inaugural Gratiaen Prize transformed what some considered a ‘diffident’, sterile Sri Lankan English literary landscape forever. The novel unabashedly described sexual scenes, skilfully employed the everyday language of the railway Burghers, and introduced uproarious humour which was rarely found in Sri Lankan English fiction hitherto. In a sense, he unshackled the “mind forged manacles” which had prevented many writers from fulfilling their talents. Muller, the man, was generous in hosting friends in his Kandy home, a conversationalist without peer, and always obliging when asked for a review which I did often during my years as editor of The Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities. Shehan Karunatilaka: I divide Sri Lankan fiction into BCM and ACM: Before Carl Muller and After. Or more accurately Before Jam Fruit Tree and After. That book and the ones that followed gave Sri Lankans permission to sound like ourselves when we wrote. You can see its influence in everyone from Ashok Ferrey to Manuka Wijesinge to Andrew Fidel Fernando to my own ramblings. I visited his book-filled home in Kandy a few times and found him every bit as colourful and as wise as you’d expect the chronicler of the Von Bloss family to be. We’re lucky to have had him. Madhubashini Disanayaka-Ratnayake: The world of English writing in Sri Lanka is a very small one. When I began writing, around 1991, it was smaller still and we knew the giants. When Carl Muller appeared on the scene with his Jam Fruit Tree, we were introduced to a text that sparkled like wine – words glinted and winked on the page like diamonds. A whole ethnic group came alive with a rambunctiousness not encountered in Sri Lankan English fiction before. I had imagined a large wild figure as the author, some walking chaos – but when I actually got a chance to meet him in Kandy, who I saw was a quiet and thoughtful man. His manuscripts were handwritten in the smallest, neatest handwriting possible – straight unwavering lines–in no way could one imagine the boisterousness they were describing. He was also something else. He was a very kind man to young writers. When my second collection of short stories came out, and I asked him if he could write a review for me, in the post came a handwritten document from Kandy. I read it with fascination. He had given my stories meanings that even I hadn’t thought of – that was the first time that I realized how external to the writer, writing could be. That kind man is no more. And I grieve with the rest of my tribe. Carl could make champagne out of water. Suddenly the world seems to have run out of sparkling stuff. Ashok Ferrey: He opened the doors for so many of us. Raconteur, wit and lovable old rogue: I am eternally grateful to him! |