A writer of everywhere

Michael Ondaatje. Pic by Basso Cannarsa

There is a reason one doesn’t often ask the writer Michael Ondaatje for an interview – not only because of a sense that he prefers living offstage, but also in fairness to his own quiet manner of supporting writers, artists and their cultural landscape.

In recent years, I have come across a number of writers to whom Michael Ondaatje has given generously of his time and detailed reading, more time that one would dare to ask for. A few years ago, I was invited to a literary festival in Toronto to speak about a book I had published – I could not think the organisers would have heard about the book, I assumed it must have been Michael who tipped my name into the hat. When I was sent the schedule for my events at the festival, I discovered that on my final day there I would be speaking in the biggest hall, interviewed by Michael Ondaatje – a sure way of ensuring that an unknown writer was heard by over a hundred people. Michael had never mentioned to me that he offered or agreed to do this. Indeed, though we prepared for the interview in detail, again because he chose to take it very seriously, we have never spoken of his act of kindness.

Reading online, I discover that Michael Ondaatje was among a small group of writers who withdrew from a literary gala organised by PEN America in 2015, to make a special award – the Toni and James C. Goodale Freedom of Expression Courage Award – to the magazine Charlie Hebdo. The writers denounced the brutal attack that had been visited on the magazine’s staff and office, following its mocking portraits of the Prophet Mohammed, but they said they could not applaud the publication for goading an ‘already marginalised, embattled and victimised’ part of the French population. They said: ‘The inequities between the person holding the pen and the subject fixed on paper by that pen cannot, and must not, be ignored.’ Salman Rushdie was among those who criticised the abstaining writers. Reading about this controversy after the fact, I remembered another story I had heard – that years ago, after the fatwa announced by the Ayatollah Khomeini that sent Salman Rushdie into hiding, preparations were made in secret for Rushdie to make his first public reappearance at a PEN Canada event in Toronto in 1992. Given security concerns and protocols, Rushdie could not be put up at any hotel and the event was only made possible because Michael Ondaatje and Linda Spalding invited him to stay at their house. These are also stories I have never heard Michael Ondaatje tell, himself. What we did discuss in the run up to this interview was how we would manage to talk about books and writing while preoccupied and worried by the current escalation of events in Sri Lanka.

Michael Ondaatje’s most public act of supporting writers in Sri Lanka has been to set up the Gratiaen Prize, to support and encourage writers in the place he was born, and which he left at the age of 10. Using winnings from his own Booker Prize for The English Patient in 1992, Ondaatje created an endowment to pay for the prize, gave it his mother’s name and entrusted its running to its appointed trustees in Sri Lanka. The Gratiaen Prize is awarded each year to the best work of creative writing in English submitted in any genre, with unpublished manuscripts and published books both being considered. Every other year, the H.A.I. Goonetileke Prize for Translation is awarded alongside.

As the Gratiaen Prize celebrated its 25th year in 2018, there also came a redoubled award for the book that spawned it, when readers voted The English Patient their favourite Booker Prize winner in the 50-year history of that prize, choosing from a decade-by-decade nomination made by a panel of literary judges. In his speech when he accepted this Golden Booker, Michael Ondaatje noted a host of extraordinary writers and books who were never awarded the Booker Prize, once again with his characteristic sense of proportion, principle and literary fellowship.

Nonetheless, the coincidence gave us at the Gratiaen Trust an excuse to ask Michael Ondaatje if we could sit down again and reflect on the longer story. The full version of the conversation will be available on the Gratiaen Trust’s website later this year – here follows a short extract from it.

*****************************

SG: What is it like to win one of these ‘summing up’ prizes?

MO: Well you know, on one level it’s fine. [He laughs] On another level it’s very embarrassing. I mean who decides this? I know my sister’s bridge club in Colombo was voting for me! I just find it very strange – when you’ve got writers like Naipaul and Penelope Fitzgerald and others and of course a lot of writers who were never even considered for the Booker. Like Sam Selvon – his book The Lonely Londoners is I think one of the great English novels of that period.

SG: It’s hard enough to award a prize in one year, let alone then try to pick from 50 years?

MO: It’s crazy, it’s like some mad horse race.

SG: It’s hardly surprising to me that you would accept an award by talking about the other writers who could have won it just as easily. In your books – perhaps in The English Patient most of all – you pay constant homage to other writers, to jazzmen, to songwriters, to painters. What has it felt like gradually to be considered a master yourself?

MO: I really don’t think about that too much. I mean, I take it with a grain of salt. I think because I find myself, as a writer, very aware of my limitations. My limitations of knowledge, say about history, literature and so forth. The real pleasure and excitement for me is to learn. I was much happier as a student than as a teacher and I did teach for a long time.

SG: What is it like returning to a book you wrote a long time ago?

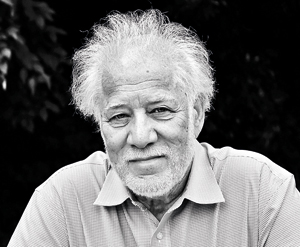

Michael Ondaatje with his friend Ian Goonetileke, after whom the H.A. I. Goonetileke Prize for Translation is named

MO: I don’t usually re-read my books once they’re finished. Once you’ve actually done the final-final-final version, you can’t bear it and you’ll never know anything more about this book than what you know now. The thing is I could never write Coming Through Slaughter now, and I feel good about that book, it was the best book I could write at that age and I would never be able to write it again. With every new book you want to write something that you cannot write; something that at that moment, at the beginning, you are unable to write.

SG: When you are writing a new book is it a similar impulse or instinct that begins them all, whichever way they then go, or do they come from very different places?

MO: I think for me it goes back to being a poet as opposed to a novelist. When you first start to write a poem it’s such a tentative thing. You have a possible first line which may get dumped and you go forward, and you’re going on more of a sort of reconnaissance in motion and in language. And when I wrote novels, I wanted to keep that element. When I began The English Patient, I had a little scene with a nurse and a patient talking at night and so I went with that and that’s all I had; that scene got built up and then there was a scene about a thief having a photograph taken of him and having to steal it back.

SG: I’m not surprised that it’s a poet’s instinct – because it’s also a poet’s voice that we hear. By the way I did want to ask, are you still a poet?

MO: I would like not to give up my licence [he laughs]. It was very difficult for me to go back to poetry after The English Patient. I’d done two books – In the Skin of a Lion and The English Patient– and I hadn’t written any poetry during those years. Then going back to writing poetry was like re-training about the line break, as well as how much you say.

I think one of the interesting things for me, which enlarged something in my writing, was that when I came to Running in the Family, after The Collected Works of Billy the Kid to Coming through Slaughter, I found I was writing not about one person but a group of people,there were other voices. When I was writing the book, I talked to everyone about Lalla, my grandmother, and they would tell me stories but I couldn’t hold it together. And then the actress Chandi Meedeniya (Irangani Serasinghe), a wonderful person, had come over for tea and I was asking her about Lalla, because she knew her, and she said, ‘listen this is important, this is how she spoke’. And then she talked for about five minutes the way my grandmother spoke. And it was the thing that opened up the whole book, not just the grandmother. I now knew the voice, the manner of speaking, and the exaggerations, the bull…t, all that kind of stuff now became easily available to me. And I could take what other people had said and put it into that voice that Chandi had given me.

**********************************

MO: I know writers who research the hell out of their books before they even start writing the first word. Which would be a problem for me, I’d be a bit bored because I’d already know all that stuff. And if that were the case there would be less pleasure for me. I usually begin with a kind of landscape, a time period and maybe a hint of one or two characters and then gradually X will become a forensic anthropologist or a horse-rider or a bomb disposal person. The profession obviously becomes very important and then at that point I will do research on say bomb disposal. With The English Patient, Kip didn’t come in till say page 120 or something, so there was no awareness of that being an important part of research until he came in. Then I did quite a bit of research but it had to be research only up to the year that Kip was in –1942 – it couldn’t be before or after that, it had to be up to that point. The research occurs simultaneously sometimes to the writing.

SG: It’s a huge relief to hear you say this because, as a beginner writer, you have that feeling you’re being a bit dilettantish to start writing, you don’t know enough yet. But perhaps you can’t possibly accumulate before you begin everything that you’ll eventually need?

MO: I don’t think you can. I mean I know John Milton planned everything before he wrote Paradise Lost, but we’re not in such a stable universe now. Things change too fast. And we are influenced not just by our own city and personality but by other forms of literature and art. Donald Richie, I don’t know if you know him, he’s a very interesting American who has lived in Japan most of his life. He wrote a wonderful essay talking about how in Japan they prize the quality of indecision in the structure of a novel. It was such a relief to read that!

SG: How far into the writing of each book – and it must vary from book to book – do you feel you know what it’s about?

MO: Quite honestly, I’m never quite sure. Sometimes you realise even during editing that you have to take something out and have a blank there. Or you’re just saying too much.

SG: And in terms of your writing and editing, have the things changed that are difficult – over the years and over the books?

MO: No, I think it’s just as hard to write a book now as it was for me at the beginning. There’s still this uncertainty about whether one can write a book. You’re in a completely new landscape and time period and you yourself have changed so utterly that you can’t go back and redo something. I begin with a hint of a character or two, I know the location, I know the time period. That’s always been the grounding. And then you’re writing. Characters are crucial for me because characters evolve and more characters enter the room or into the story and then they breed. They breed argument, they breed opinion. You’ve got the nurse, you’ve got the patient and then Caravaggio comes in and then Kip comes in, so now you’ve got a community of people who are falling in love or in argument. There’s a line of John Berger’s I’ve used as an epigraph which is ‘never again will a single story be told as though it were the only one’. And that has been very central so The English Patient is not just about Kip, it’s not just about Hana, it’s about a group of them, it’s not just an aesthetic, it’s a political statement. I can’t just have a one-point-of-view killer like Billy the Kid anymore, I need an evolving community.

It is exhausting and it’s also a huge pleasure to write and to make something and to make it deviously so it will work dramatically as well as emotionally.

SG: I’m not sure whether it is a relief or a terrible disappointment to hear you say this. One hopes that at least it gets a little easier over the years.

MO: I know! What I’ve had to do over the years is when I’ve finished a book, I need to do something completely different, for instance using different utensils. Early on, after I wrote Billy the Kid, which was my first long book, I made a documentary film about a poet. I needed to go and immerse myself in a different technique. And thereby learn something: just learning another craft was in some ways very helpful to me. The discovery is what the other thing is that you can do – it has to be something, if you had another life you could do this.

SG: If you had another life, what else might you have been?

MO: Well I guess my fantasy as a young person was I would want to be a doctor. One of the gifts. That would have been exhausting, moral, all those things are there.

MO: Well I guess my fantasy as a young person was I would want to be a doctor. One of the gifts. That would have been exhausting, moral, all those things are there.

MO: You said something about being a writer from everywhere and that to me is such an interesting thing, if one can be that. I’m obviously from Sri Lanka, lived in England, moved to Canada, so there’s a certain element of that. But there’s an interesting openness to being from everywhere that I like a lot.

SG: I remember when The English Patient won the Booker Prize, when it was going to be made into a major film, I lived in Sri Lanka and there was the great swell of pride here that our boy had done this. Feelings that are so ironic in so many ways. How have you negotiated being claimed in one place or another?

MO: You know, I’m very happy to be seen as Sri Lankan, or Sri Lankan- Canadian or something like that. For me the problem has always been with being a representative. I think that’s something I tried to avoid or distance myself from. Especially I think when Anil’s Ghost came out, people would try to turn me into a representative, an official voice, so I could talk about Sri Lanka. And I said no, there are a lot of books written about this and those are books by people who were there. And I’m not a representative – I’m one individual with this response to what happened. That was the pitfall I tried to avoid. But certainly, I think I was given a gift, that I was born in Sri Lanka, that I lived in England and then in Canada so I could have a perspective that was not just one dimensional.

SG: And in terms of your relationship with this island has the writing of those books –Running in the Family or Anil’s Ghost – transformed your relationship with the place? Because of course you left very young.

MO: I don’t know if it transformed it. I know that when I wrote Running in the Family I came back and I was refocusing my life, recapturing it. First of all, I hadn’t been back for years, so I really wanted to return and discover who I was. And then I was trying to see if I could write something – there was an ocean of stories there for me to hear about. When I came back some years later to write Anil’s Ghost, I very intentionally did not stay with my family the whole time. I was interested in not just seeing it or telling it through the window of this one family. In that sense I wanted a larger perspective, I guess.

SG: I’m struck that The English Patient in particular has such a long legacy in Sri Lanka because it led to your setting up the Gratiaen Prize. Although you describe yourself as someone who comes and goes, your presence is here, through that prize. I’d love to hear you talk about setting it up and what made you do that, especially looking back after 25 years.

MO: The lightning strike of being given the Booker was a complete surprise, and it was a gift and I just saw myself as being able to do something with that gift. I visited Ian Goonetileke one afternoon and we thought about how we could do it as a prize of poetry, or fiction, or non-fiction. As well as the idea of having a translation prize, which was to me as important. What I wanted to happen was – it seemed to me we could almost create a publishing house that published books as well, for instance translations of Sinhala books to Tamil and English and vice versa. I wish that could have happened much more. But also, I think the important thing that happened was we were going to give a prize for the best book in all of these fields. Then, after a few years, someone said ‘but the best books are not published, people find it difficult to get a book published’ and at that point it was decided the prize could allow unpublished books to be considered. I think in fact since then most of the prizes have gone to unpublished books – which I think is great, that’s something very important for us to recognise. And you know I wanted the prize to be something that in its own way would make public that unknown literature – an important thing for a culture.

SG: I know you’ve chosen, I think very wisely, to let it run locally. You haven’t been heavy handed, perhaps also conscious that if you did speak, your voice would weigh disproportionately and that you’d be shaping it from afar. But it’s still very interesting to hear your thoughts, any reflections that you’ve had over the years, or any thoughts or wishes that you’d have for the prize going into the next period.

MO: It’s difficult – in many ways you and the others are much more aware of what should be done, what needs to be done. I do wish that the Trust could also have been a publishing house and publish the books that won which so far had not been published. And to have had more of an awareness of books being translated between the three languages – much more of that. But that seemed to be difficult to do. Also, I think that whole idea of opportunities for writers to meet editors and publishers – some from within the country and some from outside the country – I think that would be a really valid thing to try and grow.

SG: And to take the question away from just the Sri Lankan context – do you think that the world has changed for writers? Has the cult and culture of authorship changed over the time that you have been a writer yourself?

MO: Well it should change, you know, and I think it has. There’s a public role for the writer that wasn’t there before, though it also was obviously there before. I think the problem now is more to do with media and the fact that media governs the frame. So, it might be Mick Jagger, Mick Jagger, Mick Jagger, and nobody else in that field of music. There’s the whole thing about writers becoming famous and then they’re the one person that is referred to all the time, as opposed to much more interesting younger and lesser known writers. I think that’s a problem now and I don’t know what one does with it. It feels like everything is completely governed by the media or Amazon or something.

SG: It’s also that feeling that the noise around books distracts you from the reading of them.

MO: No, no, I know. In the last few months, I’ve gone back to reading books from an earlier time, say 20 years ago, or more. The present world of publishing feels like rush hour, with all the constant media that you are being handed.

SG: I must let you go. I suppose there is a last question – to me, reading your work, I feel that you’ve really allowed your voice to change and deepen over the years. Maybe that’s not something one is in control of. But looking back over your work, do you feel that your voice has changed?

MO: Oh, I hope so, I hope so. Not that I would want to change the voice of some of those earlier books. I think there’s pacing – not just pacing, it’s a voice. I do think the voice in Warlight is very different to the voice in The English Patient, and I don’t think I could have had that voice without The Cat’s Table. But something changed – maybe with the voice of the young person, or the narrator who is both young and old in both of those books. Even with Divisadero, which a lot of people couldn’t stand, I don’t think I could have got to The Cat’s Table without Divisadero. There is a series of tunnels one goes through to get to the next one and you’re not quite sure if it’s working or not, but I would hate to remove that risky path. But yes, my books have changed. I hope so.

- Michael Ondaatje’s latest book is Warlight, published in 2018.

- Sunila Galappatti is stepping down today after six years as a trustee of the Gratiaen Prize.

- The Gratiaen Prize and HAI Goonetileke Prize for 2018 will be announced tonight.