Sunday Times 2

Dancing in the darkness of a climate crisis

Globally, Sri Lanka ranks as the sixth most vulnerable to climate change. But this reality has not taken hold in Sri Lankan polity. This is partly because we do not have sufficient analysis of climate change impacts nor a communication strategy to help public and policymakers understand it better.

When many countries are planning large-scale interventions based on specific localised impact assessments, we are literally dancing in the dark.

When many countries are planning large-scale interventions based on specific localised impact assessments, we are literally dancing in the dark.

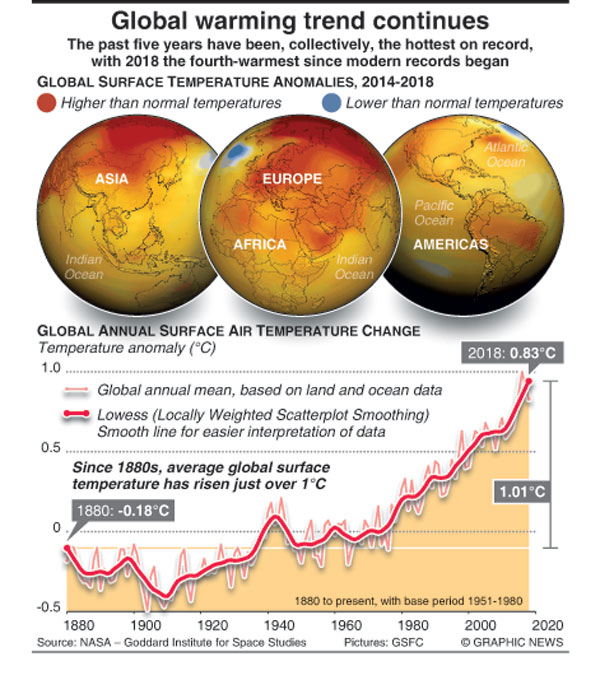

The four years from 2015 to 2018 were the warmest globally since records began in 1880, a trend mirrored in Sri Lanka. This country saw a sharper rise in temperature between 1960 and 2000 than the global trend while 2016 was the highest recorded. The impact has been substantial.

There is significant bleaching of coral reefs globally. Both Pigeon Island and Bar Reef in Sri Lanka were severely affected. We still have a few vibrant coral reefs left, mainly off Mannar, but their survival is questionable beyond the next heat wave that hits us.

The IPCC’s (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) recently released report titled ‘Global Warming of 1.5oC’ indicates why. The probability of coral reefs surviving under a 2oC temperature rise (the target scenario for Paris climate agreement) is less than one percent. If the world ends up with an increase of 1.5oC (the aspirational target), it will result in a 70-90 percent decline in existing reefs. This does not sound promising for the few remaining local coral reefs.

Why does this matter? More than 40 percent of marine species spend part of their lifecycle in coral reefs. Their destruction will result in a massive marine-extinction event rippling to fisheries and industries like tourism. Our tourism sector is eager to market our natural heritage, but is conspicuously silent on its own existential crisis.

But there is a different question, about who we are as a people, as a civilisation, and the morality of our actions or inactions. Are we still human in a world without coral reefs? Do we have the capacity to grieve for the ongoing and impending loss?

Those who grieve the most are the ones engaged in conservation. I had been working with Dhanushka Mahanama on mangrove conservation. I was always charmed by his love for his work and the energy he puts towards educating local students on the value of mangroves. He is a giant of a man, with a booming voice, yet gentle and jovial. When he wanted support for re-growing coral reefs that died out in the South, I was dismissive, noting that South-Western Sri Lankan coral reefs cannot be made anew due to sea temperature trends.

I saw the resignation on his face, still marked by steely determination. The brutality of my dismissal of his efforts crippled me afterwards. I felt like an executioner, making decisions about who and what should live.

A global revolution is emerging, led by teenage girls fighting for the future of the planet. Inspired by Greta Thunberg, thousands of schoolchildren have been walking out of schools since August 2018 as part of coordinated action on climate change.

They are facing a world marked by an unstable climate system, mass extinctions, ecosystem collapse, rising sea levels, and refugees that will come out of this chaos. This is not something in the future, but what is happening now, which will exacerbate in the future. What climate change will herald to their future cannot be undone by anything taught at school.

They are facing a world marked by an unstable climate system, mass extinctions, ecosystem collapse, rising sea levels, and refugees that will come out of this chaos. This is not something in the future, but what is happening now, which will exacerbate in the future. What climate change will herald to their future cannot be undone by anything taught at school.

Human civilisation emerged in an era of stability in the global climate system across 7,000 years. Greenhouse gas emissions since the industrial revolution have already destabilised the climate system, and are triggering changes that are difficult or impossible to reverse.

Global surface temperatures have already increased by about 1oC. It is felt through melting of glaciers, destruction of vulnerable ecosystems such as coral reefs, rapid extinction of species, changes to habitats and extreme climate events. Reading any report on climate change, the panic among scientists is evident.

And when scientists start panicking, it is past the time for us to be merely concerned.

The basic premise of sustainable development, the often misunderstood phrase, refers to protecting future generations. Any climate observer will know that we have spectacularly failed in this. So the children of the planet are right to strike, urging us to act.

We have a short period to reverse the trends to save our ecological heritage.

When scientists are becoming alarmed, and teenage girls are walking out of their schools to march for their future, and conservationists grieve about mass extinctions, it is time for us to panic.

(The writer is a sustainability and energy specialist)