A roller coaster ride of people and places

View(s): John Gimlette’s journey to Sri Lanka starts in a seemingly dangerous part of the world where rival Tamil gangs roam slicing each other with machetes. In one year, he writes, 15 gang members died and the city did not notice.

John Gimlette’s journey to Sri Lanka starts in a seemingly dangerous part of the world where rival Tamil gangs roam slicing each other with machetes. In one year, he writes, 15 gang members died and the city did not notice.

The book begins in a temple where fallen leaders of a ruthless terrorist movement are venerated. The author enters into a fragrance of incense, the sight of a dozen half naked priests and his eye is drawn to a notice where worshippers are asked to donate ten thousand pounds (about USD 15,000). He does not mention having made any donations and perhaps sensibly so as he writes that the temple has been accused of terrorist financing. He lives in a neighbourhood which has been a hotbed for the formation of rival armed groups that killed civilians and each other.

Where could this be? In the year 2015, it may come as a surprise that this is in Britain (and alarmingly for me around seven miles as the crow flies to where I live). Therefore it must have been with some relief that he left his neighbourhood of Tooting in the suburbs of London and travelled to Sri Lanka which he says is the ‘most beautiful country in the world’ echoing the sentiments of an illustrious pedigree of travellers from Marco Polo to Mark Twain. The dust jacket states he has travelled to 80 countries and such a claim is therefore not one to be taken lightly.

However, beautiful as it may be, this country too must stand the test of Gimlette’s ‘rogues test’, and his at times withering portrayal of people in power. Gimlette could have chosen to start his book from any one of a thousand choices of tropical settings from romantic to idyllic. But a journey begun from his gentle Tamil neighbours in suburban Britain, supporting a terrorist group overseas, shows his eye for the bigger picture; an ability see the unexpected.

The book is a roller coaster ride of people and places, delivered with varying pace and style. From the fast paced beat after arriving in Colombo, it deftly weaves a complex tapestry of pace and anecdote, swerving from journalism to poetic prose, nostalgia and an examination of the human condition. The way he writes about how the human torrent carried him along at the holy city of Kataragama reveals that at the heart of a good travel writer lies a mastery of creative writing. This is not a book that sets out to answer a specific question or to offer solutions. It is like a fine Sri Lankan meal of curry; a mix of spicy dishes to be consumed slowly and pleasurably. It’s a skilful mosaic of past and present with the ghosts of the past lingering wherever he casts his eyes.

This book is a patchwork story of people with an eventful recorded history stretching back over 2,000 years, seemingly in a never ending flux of wars and glorious civilisations that die away, to start all over again. A country where its people are now enmeshed in an interwoven global community of economic migrants. He warns that most people leave Sri Lanka feeling that they understood it better than when they arrived. But Gimlette seems to do better because he travels with an open and enquiring mind. In recent years, Sri Lanka’s literature in fiction and non-fiction has been greatly added to after the Tsunami and both during and after a 30 year war with separatists. This is understandably so, as these are important and tragic events and provide a conduit to explore what makes us human and what unleashes the demon within us.

It is often the case that a writer has a hypothesis or a true story to tell and when delivered as a travel book, he uses his travels to add flesh to the bones of a story. Gimlette’s book is not a quest to reveal a particular story of what happened; rather he despairs at times whether anyone will understand the country. But in not trying to explain, it is a refreshing viewpoint as he is not travelling to research and fill gaps in a hypothesis, but instead for the country to tell its stories to him. He is a traveller collecting beads of stories which he elegantly strings together to make a whole. This is no easy task, and he skilfully assembles it with empathy and an intellectual curiosity to provide context to the varied viewpoints, fractured lives, inspirational and often sad people he meets. It is a wonderful travel book imbued with a gentle sense of humour as well as acid observation.

Gimlette is a master of metaphor and pithy phrase. Colombo, he says, is a city built by invaders and besieged by commuters. I can think of no shorter sentence that brings together the city’s historical past and its present urban planning problems. Gimlette is a barrister by profession and is trained to take stock and summarise succinctly. Give this weapon to a travel writer and there are piercing analyses to those alert enough to pick up on it. Every page ripples with skilful metaphors where words paint imagery, dissects a nation and is occasionally gently scornful.

He has a good measure of its commercial capital, and he writes that the commuters arrive ‘as a twitching mass of neurosis’ and ‘they are already late and a light panic settles over the city’ and when they leave they are a ‘hot angry reptile snaking out of town’.

The amount of research Gimlette does before a book like this is extraordinary. He typically takes three years to research his subject and makes multiple visits to the country. But for those who know the country, his eye for detail and the ability to grasp the metabolism of the country is evidenced in short comments like ‘outside I could hear sweeping, the signature sound of a new Sri Lankan day’. A travel writer on a short, one-off visit would not pick up on things like this. Nor would a person who was not constantly receptive to the rhythms of a country.

I am not without a few minor quibbles about his views and comments. Some things in the book are at odds with my personal experience. He claims that former President Mahinda Rajapaksa is known to the faithful as Vishva Keerthi Sri Thri Sinhaladheeshwara or the Universally Glorious Overlord of the Sinhalese. I had never heard this before. A theme in his conversations with the great and good who invited him for their parties in Colombo was that they did not travel much out of Colombo, sometimes not venturing beyond the suburbs. This contradicts with my experience of Colombo’s cocktail circuit. But as I said, these are minor quibbles and and more importantly there is evidence in abundance that he often sees things that locals will overlook.

What you see is what you know. In his journeys he notices the spoil heaps in Mannar of the pearl fishing industry where in a peak year 80 million molluscs were harvested and their bodies left to rot on the seafront. He deftly weaves the past and the present. One moment you are on a navy gunship and on the same page you feel the presence of the Portuguese rag bag army wandering around the coastal towns half clothed and hungry. He has a gift of seeing the past in the present and evoking their ghosts onto the page. This book is not a conventional travel narrative with a clear chronological thread with an identifiable beginning and end, with people met on the way providing the human interest in the manner of the ‘The Snow Geese’ by William Fiennes. It’s a series of separate journeys premeditated to take form in a book but sculpted in a way that most chapters can be read as independent essays.

The journeys and stories are threaded together not necessarily to make sense of what Sri Lanka is, but to observe with empathy. The people he meets are central to his style of narrative. A former President who charms him with her charisma, a senior minister in whose presence his entourage is too overawed to speak, a campaigner against child sex abuse who sets him off to launch his own investigation, a former gunboat commander who holds no malice to his enemies and so on. Gimlette is a literary chameleon, morphing into the landscape he is in. As he travels up to Kandy he is a military historian who paints a vivid picture of how war was waged by the Kandyans against the British; in the highlands he is empathic, subtly conveying the loneliness of the British colonial tea planters. In the East he is a war journalist picking his way through a ruptured city and the survivors of a brutal civil war, and in the countryside he is a creative writer where every sentence seems exquisitely crafted.

I wondered what this book was about as I read it and what motivated the writer. Insightful, painterly and with sharp observation, but unusual in that I could have shuffled the order of the chapters and not lost much of the quality of the book as it did not need a definite narrative direction. This is not a quest to uncover a secret or the desire to explain the genesis of a war or revolution or the chronology of social injustice that led to a multitude of these. As I was reaching the end of the book I think I understood how I could draw an analogy to what this book was about. Imagine a naturalist swimming over a vast reef and pointing out how in one part of the reef the fish are solitary and in another part of the reef they live in large schools; they are differently coloured and differently shaped, but they co-exist, at times in apparent harmony and at times in conflict. Gimlette is snorkelling along a vast reef inhabited by people and evoking vivid portraits of individuals and groups; he is a literary anthropologist. His vignettes of people cast people in the context of their physical landscape and circumstances in way that is accurate and masterfully economic. For example, some of the people he sees in the Vanni evokes dried-up souls with an aristocratic demeanour.

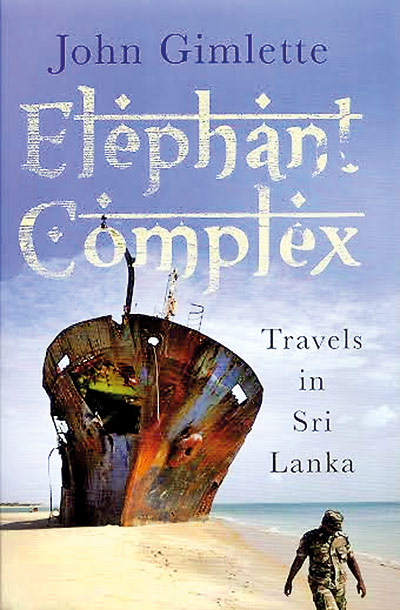

| Book facts: Elephant Complex by John Gimlette. Quercus Publishing Limited: London. Hardback. 518 Pages. Published in 2015 Reviewed by Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne |

Gimlette’s journeys take him all over the island. Kandy, the last to fall to foreign powers, Galle in the south – now partially fallen to foreign hands as the island opens up quite rightly to foreign direct investment, and Nuwara Eliya and Haputale in the highlands, the East in search of the last aboriginal people, war torn Jaffna and the picturesque islands off the northern peninsula. People reading this book, will I am sure, be inspired to visit some places that they may not have considered otherwise. If they have time to reflect, it may change how they perceive a place. But this book is not a travel guide to shortlist your list of places to see and post your selfie on social media. At its core, it is a work of literary writing, a complex tapestry beaded together with detail, acute observation and a gift to evoke a sense of place. Page after page is illuminated with luminous writing where even buildings – shattered and spent in war – come to life.

W. G. Sebald in the ‘Rings of Saturn’ travelled through landscapes which were grey and melancholy and looked at the world with sad eyes. In Elephant Complex the story is narrated largely through people who have been through the grey filter. People damaged and bruised with war or social injustice who seem to live in a state of constant upheaval or half-existence. Towards the end of the book Gimlette meets again the spiritual leader of the Tamil temple in London. He boasts that he would send ‘KP’ (a procurer of arms for the Tamil Tigers) British Pound Sterling 300,000 (approximately USD 450,000) in a pop to fund a bitter war that saw the Tamil Tigers forcibly conscript children. But several chapters later nearing the end of the book, the spiritual leader is on the run, pursued by writs from British Tamils.

In his closing chapter Gimlette walks on a lonely sand promontory where the war funded by the spiritual leader ended. He leaves feeling rage at the thought of the civilians trapped between two armies being mown down by shelling. But as he travels south, something remarkable happens. He falls in love with the country again and acknowledges that he feels guilty about it. Although we see in the acknowledgements that he has made many friends, they do not figure prominently in the main story. The book is largely filled with people he met on the road. We can see with writers whether it is Gimlette or Sebald that a person’s affection for a country or place is indefinably complex with physical landscape and history just as important as the people who presently occupy it.

Gimlette deftly weaves between different strands of the human story with a curious cast of characters. Through Gimlette’s lens, many are baffling and strangely disconnected with western sensibilities. Skilful as his portraits of people and places were, I wondered if gaining a measure of Sri Lanka would elude him as he had warned about writers before him. But maybe he has understood what this multi-layered reef-like nation of people is about. As he visits an underground military complex of the defeated Tamil Tigers, he writes ‘One day, people will wonder what it was for, and then, perhaps, they’ll fight its battles all over again’.