Sunday Times 2

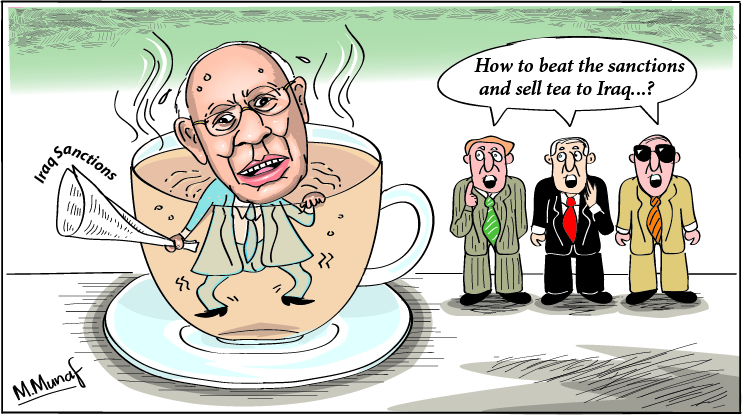

Tea without sympathy for our witty envoy

View(s):UNITED NATIONS – After Iraq’s invasion of neighbouring Kuwait in August 1990, the UN Security Council hit back with rigid economic and military sanctions against the Saddam Hussein regime in Baghdad. In the arid, water-starved Kuwait, there was a joke that every time the Kuwaitis dug for water, they struck oil. So the boundless oil riches were too great a temptation for the Iraqis, who were planning to annex Kuwait and declare the sheikhdom an integral part of the Republic of Iraq. And that’s an unforgivable sin at the UN — unless you are Israel protected by the US.

But at the United Nations, there was a remote Sri Lankan angle to the Iraq story. Ambassador Daya Perera, a hot-shot criminal lawyer of his generation, was Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representative (1988-1991). He was saddled with a problem at the tail end of his diplomatic career — to ensure our tea shipments were exempted from the UN embargo. Iraq was one of Sri Lanka’s thriving tea markets in the Middle East earning millions of hard-to-get foreign exchange. We just couldn’t afford to lose that market.

But at the United Nations, there was a remote Sri Lankan angle to the Iraq story. Ambassador Daya Perera, a hot-shot criminal lawyer of his generation, was Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representative (1988-1991). He was saddled with a problem at the tail end of his diplomatic career — to ensure our tea shipments were exempted from the UN embargo. Iraq was one of Sri Lanka’s thriving tea markets in the Middle East earning millions of hard-to-get foreign exchange. We just couldn’t afford to lose that market.

A terse but light-hearted telex message landed on Daya’s desk, direct from the Presidential secretariat, requesting him to find a speedy solution: “Either you get us an exemption, or else the Sri Lanka Mission staff will be paid next month’s wages in tea.” But clearly no sympathy.

At the staff meeting next day, Daya gave the bad news with good-humoured grace: “If we fail, I will have no choice but to send you guys hawking Sri Lankan tea in the streets of New York to prevent us from going on the dole.” And that’s short of waiting on a street corner with a begging bowl presumably covered by diplomatic immunity.

The Security Council resolution, however, had an apparent loophole — depending on how you would interpret it. The economic sanctions exempted “foodstuffs” and “strictly for humanitarian purposes.” Can tea be categorised as an essential foodstuff and does drinking tea serve a humanitarian purpose? Like a skillful defence lawyer in court, he did convince that our tea, a staple food in Iraq, necessitated an exemption from the embargo.

The Security Council resolution, however, had an apparent loophole — depending on how you would interpret it. The economic sanctions exempted “foodstuffs” and “strictly for humanitarian purposes.” Can tea be categorised as an essential foodstuff and does drinking tea serve a humanitarian purpose? Like a skillful defence lawyer in court, he did convince that our tea, a staple food in Iraq, necessitated an exemption from the embargo.

As a high priced lawyer, Daya grudgingly practised the art of “free speech” because every single sentence he uttered in court cost his clients hundreds and thousands of rupees in cold cash (before inflation). By sheer accident, the very first day Daya walked into the UN, he was pressed into service on an unexpected assignment. Since Sri Lanka was one of the vice-presidents of the General Assembly, the UN’s highest policy making body, he was called upon to preside at one of the sessions at short notice. As he climbed down the podium at the conclusion of the meeting, the irrepressible Daya turned to one of his deputies and said jokingly: “This is the first time I spoke without charging a fee.”

Perhaps one of his remarkable achievements was his successful campaign for the election of Justice Christopher Weeramantry as a judge of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague (1991-2000). But the judge’s superlative credentials made Daya’s effort relatively easier. As part of the lobbying, Daya personally met with ambassadors from virtually all of the member states, one-on-one.

The (ICJ) is the principal judicial body of the UN composed of 15 judges elected both by the General Assembly and the Security Council voting simultaneously so that the decision of one body does not influence the other. Being a lawyer himself, Daya was aware of the significance of the ICJ and how prestigious it was for Sri Lanka.

While on a daily campaign trail at the UN, Daya got one of his junior staffers to accompany him carrying several publications authored by Justice Weeramantry. As he was canvassing an African ambassador for his vote, the envoy mistakenly looked at the junior staffer and told Daya: “Mr. Ambassador, don’t you think your candidate is too young to be on the International Court of Justice.” “No, no, no”, said Daya,”he is only my staffer. Our candidate is not here.”

As Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representative, Daya chaired the Ad Hoc Committee on the Indian Ocean and also the UN Committee on Israeli Practices (dealing with human rights violations in the Occupied Territories). As chairman of that Committee, he held court at least twice a year, in Amman, Damascus and Cairo, where Palestinians lamented the sufferings they under went in Israeli occupied territories in Gaza and the West Bank.

A strong supporter of the Palestinian cause, Daya, like all our ambassadors who chaired the same committee, was strongly critical of Israeli treatment of Palestinians, as reflected in his reports following visits to Arab capitals.

At the UN, I built a close working and personal relationship with Daya during his tenure in office (and later as Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner in Canada). I was once in his office when he dumped on my lap a file marked “Confidential.” But even before I could open the file, I had visions of several lead stories in the Sunday Times, including perhaps details of the rumoured friction and bitter battles between Daya and his Foreign Secretary.

But as I opened the file, he looked at me and said in characteristically Sri Lankan jargon: “You bugger, you can read, but you cannot write.” He was riding a fine line between a friendship and the ethics of confidentiality — and having the best of both worlds.

Still, I think I had the last word when I told him: “Daya, you are treating me like a eunuch in an Arabian Nights harem. I can see all what’s going on, but I cannot do anything myself.” He broke out in loud laughter.

The write can be contacted at thalifdeen@aol.com