Red, the colour of his childhood

View(s):As the colourful, slogan-shouting and flag-waving May Day processions take to the streets on Friday, in the minds of the older generation would be created the image of the ‘Father’ of the Labour Movement in Sri Lanka, Alexander Ekanayake (A.E.) Goonesinha.

This is the man whose statue, depicted wielding an upraised hammer, adorns the entry to Goonesinhapura just beyond Pettah, straggling uphill towards the august Supreme Court complex at Hulftsdorp.

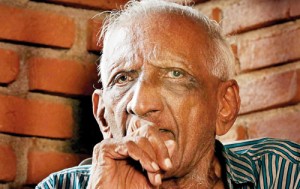

Reflecting on the past: Ananda talks about his father A.E. Goonesinha. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Much has been written about the public life of Labour Leader A.E. Goonesinha, who was the pivot around which the workers’ movement grew and spawned trade unions and who was instrumental in forming the Ceylon Labour Union way back in 1922.

What of his private life?

It is to find out who this man behind the workers was that we make our way to the home of Ananda Goonesinha in Malabe on Tuesday. Fondly referred to by his loved ones as ‘Ana’, he is the one and only son of A.E. Goonesinha, with two sisters, Lalitha and Iranganie, after him.

While Lalitha lives in Colombo 7, it is with a tinge of sorrow that Ana recalls the untimely death of their youngest sister, “a brilliant singer and actress” a while ago.

Ana then reaches into the innermost recesses of his memory to create in our minds a picture of his father, dubbed the ‘Maha Kalu Sinhaya’, who stood up for the rights of workers in the face of much hostility from the British colonial rulers.

As he himself says “90 and a half” he may be (his birthday is on October 13), but life as a child in the family home of A.E. Goonesinha and Caroline Adeline Rupesinghe is still vivid. Ana was born in 1924.

Laughingly acknowledging that sometimes their surname is spelt wrong, he reminisces about how “extremely well-dressed” A.E. Goonesinha was, always in English lounge suits topped off by a topee with a red band around the side. “The topee which was a hat which the British wore later became ‘thoppi’ in Sinhala,” he smiles.

The memories flow forth about his father owning one car earlier and then two, a big one and a small one, and before touching on his trade union activity, he dwells on how he was a strict disciplinarian. Kandyan dancing, he wanted Ana to learn, while also bringing in musicians to teach him to play the violin. Whenever his father could spare the time which was rarely, he would stop awhile and listen to Ana play, with waltzes, especially the ‘Blue Danube’ being his favourite.

All set for May Day: The statue of the Labour leader gets a wash-down

There were no crowds in their home (down Theatre Road, Wellawatte, then Flower Road), for A.E. Goonesinha had a building for the Labour Union and all his work and meetings were there. He battled for the rights of workers when there was no such thing as trade unions. “He was supporting and helping the workers,” says Ana, adding that he had a penchant for it.

Soon after leaving school, A.E. Goonesinha, who had been born in Kandy and had his early education at Dharmaraja College there, then at St. Joseph’s College and Wesley College, Colombo, did a stint at the railways, before gravitating towards journalism. He immersed himself in editing a paper called the ‘Search Light’ in support of the National Movement for Freedom.

The flame to fight for workers’ rights was sparked after he vehemently opposed the poll tax, says Ana, explaining that every adult male had to pay two rupees, “a lot of money” at that time per year, to the colonial government. A.E. Goonesinha stood firm with a resounding ‘No’ to the tax and the British government’s penalty was ordering him to perform labour work on the roads.

It was then that people rallied around A.E. Goonesinha, with the numbers swelling from 20 to about 20,000 as more and more joined and worked by his side. “The British didn’t have enough tools to give all of them,” says Ana, explaining that his father also had a couple of strong supporters including George E. de Silva of Kandy. This protest led to the abolition of the poll tax in 1923.

However, not much did A.E. Goonesinha talk about his activism at home, but Ana does recall how, when his father introduced ‘Labour Day’ (as May Day was known then) along with the colour red for everything associated with it in 1927 though, he was a little boy but tagged along in the procession. “Red was the colour of the workers and not any political colour,” says Ana, going back in time to bring out memories of fun and dancing that accompanied the processions which ended with a concert at a public playground.

It was much before his son was born that in 1915 A.E. Goonesinha not only formed the Young Lanka League, along with lawyer Victor Corea, to battle colonialism, but would also moot the Lanka Workers’ Association which would be the torch-bearer for worker organizations and trade unions. This was also the year that he would be imprisoned having been implicated with the riots.

The day Ana and Rachel signed on the dotted line: From left are sister Iranganie, father A.E. Goonesinha, mother Caroline, the groom and the bride

In 1922, to fight against poor worker wages, A.E. Goonesinha formed the Ceylon Labour Union, with a membership of only 25. This heralded organised trade unionism in the country. He also established the Ceylon Mercantile Union which would grow into the Ceylon Mercantile, Industrial and General Workers’ Union led by the late Bala Tampoe.

A.E. Goonesinha, the doughty upholder of rights, we learn from other sources, had held the first Labour Day in 1927, with the introduction of processions with bands, drummers and dancers later. This vibrant procession would wind its way from Price Park to Galle Face Green. May Day had been declared a public holiday much later in 1956 by the then Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike.

Fresh in the minds of the older generation is also the tramcar workers’ strike where A.E. Goonesinha compelled the owners of the tramcar service, Whittall Bousteads, to settle the strike, after mobilizing tramcar users to boycott the service and students to join the strike.

Our chat with Ana digresses to take in a little about his own life…….attending the Baby Class at Ladies’ College, joining Royal Prep and Royal College. When he got promoted to the big school it was the Centenary Year of 1935, he says and he and his classmates are known as the ‘Centenary Group’. Matter-of-factly, he points out that “all are dead” except himself and Walter Mendis of distillery-fame.

Thereafter, Ana entered the University of Ceylon in 1942 — the year that this institution of higher learning had a name-change from University College – securing a ‘free-studentship’ as he had topped the batch which sat the examination to secure places for the Arts Faculty.

After passing out from the university, having come under the influence of the Trotskyites, Ana had been reluctant to sit the Civil Service Examination and become “a slave under the British”. Instead, taking the share of money bestowed on him by a maternal aunt, he headed to the Inner Temple to read for the Bar in England. By this time he had met pretty Rachel Wickremesinghe (first cousin of Esmond Wickremesinghe, father of Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe) at a matinee of ‘Stormy Weather’ at the Regal.

“When I went in late, cycling from home to the cinema, there was only one seat left and it was next to Rachel. The moment I sat beside her I was enamoured,” says Ana. Suddenly breaking into song with a few lines……..‘Don’t know why….There’s no sun up in my sky’, sung by Actress Lena Horne, he says the “amazing thing was that it was a fortuitous juxtaposition”.

The registration of the marriage having taken place, “signing on the dotted line’, in his words, before his departure to England, Ana concedes that he “wasted time and money” over there, returning home after being issued an ultimatum through an air-letter by Rachel that if he did not come back she would divorce him.

The summons brought “immediate sanity to my temporary insanity,” he says with wry humour, after which he engaged in different jobs, mainly in the shipping field and also looked after his young family of a daughter and a son. There is a note of pride when he speaks of how he “put the house in order” at the Ceylon Shipping Lines which was in the doldrums, at the behest of then Shipping Minister Lalith Athulathmudali. The deadline was three months but he got the job done in a month.

The history of Sri Lanka and also his father’s life, meanwhile, had changed course. Ana recalls a grand tea-party that his father hosted when he was Mayor of Colombo in 1940. A special guest at their home on Rosmead Place was Governor Andrew Caldecott who did not want tea, only whisky. With his father being a teetotaller, his uncles had been despatched to get the choice of drink of the Governor.

After Sri Lanka had gained independence, by 1951, A.E. Goonesinha was the Minister of State in charge of Ceylonization which was to provide more employment to Ceylonese in the private sector which up to that time was dominated by foreigners. With his father losing the election in 1952, after contesting the Colombo Central seat, he had been sent to Indonesia followed by Burma, as Ambassador.

In his absence, he “made” Ana take up the trade union work that was very close to his heart. Ana’s mandate was to look after the interests of the Labour Union as well as the Bank Clerks’ Union, including overseeing a strike and negotiating with bosses to win workers’ rights and get a fair deal, which he did with general knowledge and common sense.

Even after A.E. Goonesinha’s return, he once again faced defeat at the next election, as he had lost touch with the people.

In the 1960s, Ana’s father’s health was on the decline after two heart attacks. It was in 1967 that he suffered a third. Admitted to the Colombo General Hospital and treated by Dr. Wickrema Wijenayake, Ana had gently been told by this doctor who was his classmate that there was “nothing critically wrong with my father but he seems to have lost the will to live”.

A.E. Goonesinha, who changed the lives of thousands of workers for the better, never recovered. He was dead at 76.

Asked to describe this powerful personality who could persuade workers to down their tools at the ‘drop of a thoppi’ Ana says…. “He was a determined innovator of assistance to workers and obtaining their rights. Nothing and no one could stop him.”

It is ironic that Workers’ Day or May Day as it is called now, when those who toil and labour all year round come out onto the streets in their thousands, is the day that A.E. Goonesinha was born back in 1891.