Slavery in our own backyard

Prof. K.D. Paranavitana, well-known historian, takes us back to a murky

past during Dutch Ceylon in the 17th and 18th centuries

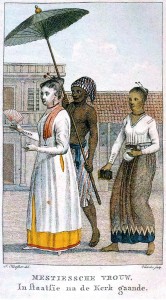

Strange would have seemed the line of people making their way to church on a sunny Sunday morning. Dressed in their Sunday best, the line would be led by the ‘master’ or ‘mistress’ followed by their slaves – one carrying a parasol, another a box of betel and a spittoon and a third a chair on which the master or mistress would sit during the service.

Was this in America notorious for its slaves and slave trade? No, this was Dutch Ceylon in the 17th and 18th centuries and what more proof do we need but the very area that many of us pass through without batting an eyelid or work in without giving a second thought to its name – ‘Slave Island’ in the heart of Colombo. Or for that matter the collection of different types of chairs which the slaves had carried, which at the demise of the masters had been donated to the Wolvendaal Church in Colombo and can even be seen today.

It is before we plunge into the murky dregs of slavery in Ceylon with Prof. K.D. Paranavitana, well-known expert on all that is Dutch, that he shows the Sunday Times drawings by famous Dutch artist Jan Brandes on “exotic” subjects, all with the essential detail of slaves.

The exquisite drawings of ‘this Dutch traveller in Batavia, Ceylon and Africa’ include an Elephant Kraal in Ceylon with slaves going about hither and thither carrying thick rope to tie up the captured wild elephants and coconut fronds to feed them and a European being carried on a palanquin.

Among the more mundane are a painting of a ‘Mixties’ (the offspring of a European and a local woman) on her way to church dressed in all her finery, while a male-slave shades her from the sun and a female-slave steps up behind her with the betel box and spittoon. Then there is also a sketch of a domestic scene, with an infant crawling on the floor under the watchful eye of a slave who is sewing.

“Slavery was foreign to Ceylon and even during the period of the Dutch was not an arbitrary institution,” points out Prof. Paranavitana when we meet him on Monday, as he makes ready to deliver a lecture on this subject to the Ceylon Society of Australia, Colombo Chapter, at the Organization of Professional Associations on Friday.

Reiterating that slavery in Dutch times cannot be compared to shameful Afro-American slavery, he says the concept was somewhat different in the eastern world. Even before Dutch times, it was an accepted practice in Arabic countries.

“All the hard or unpleasant work of the master was performed by slaves,” he says, adding that it was much later that slaves became a commodity to be bought and sold. Even when the Portuguese first arrived in Ceylon, they had brought African slaves with them but there is no trace of them.

It was when the Ceylon Society of Australia invited Prof. Paranavitana to deliver a lecture on slaves in Ceylon during the Dutch period a couple of months ago that he turned his attention to this interesting topic. “I had heard about slavery in Dutch Ceylon, but not seen documentary evidence,” he says, but then began in earnest to look up original sources at the National Archives.

The establishment of the port cities first by the Portuguese, followed by the Dutch led to the birth of a new society in Colombo, Galle and Jaffna. In these new “fairly lively port cities”, according to Prof. Paranavitana, there emerged a luxury and lascivious class of people. The new society was of ‘triple formation’ — Europeans, Eurasians and Asians. In the east, around the second half of the 17th century, the Europeans had a considerable number of household slaves at their beck and call and were entirely dependent on them, not even bothering to pick up a handkerchief from the floor.

Although the Dutch East India Company (VOC) considered “slavery to be despicable in principle, in practice it was considered a necessary evil”, for slaves were used to build fortifications, for domestic work and to engage in agriculture.

Quoting from his findings, Prof Paranavitana says that the policy of the Dutch East India Company was not to enslave local subjects residing in the territory under their rule. Views about local inhabitants are well expressed by German traveller Wintergerst in 1668 who remarks that the local people were reluctant to be slaves: “… I was once sent with two other Europeans and 63 Malabar slaves (since the Singlese will die rather than become slaves) to go 11 miles inland into the king’s territories to bring wood.”

The urbanites of those times comprised Company servants, European free citizens and the mixed population which included Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims, Chitties, slaves and convicts. The population in Colombo in 1688 according to ward superintendents (wijkmeesters) was 7,500, excluding lascorins (hired local soldiers), Company personnel in the barracks and company slaves. Company servants alone numbered about 1,500 and Company slaves some 1,520.

Prof. Paranavitana: Tracing slavery

Some Company slaves had been put to work in the immediate vicinity of Colombo and they laboured at fortifications, loading and unloading of ships and felling trees. Records also reveal that some slaves were brought from South India to meet the increasing demand for labourers and cultivators, he says, pointing out that as the slave trade was considered illegal, the Company refrained from making any direct statements in its documents.

“Therefore, information on slaves has to be gathered from indirect sources,” he points out, citing the cases of the vessel, ‘Slot ter Hoge’, which had left Batavia in 1783 with at least 25 slaves and the boat ‘Haasje’ in 1790 with 27 crew and 17 slaves.

The slaves were brought to Ceylon from two South Asian ‘circuits’, he has found. Malabar, Tanjor, Kanara, Bengal in South India and Arakan (Myanmar) Malaysia, Indonesia,

The sketch of a European being carried on a palanquin reproduced from ‘The World of Jan Brandes (1743-1808)’

Sulavesi, Java, Bali and Ambon. However their identification turns out to be a difficult task for they were not baptized, had been renamed by the master/owner, there was no mention of their ethnic background or their sex and only their first name was used. Some had been given classical names such as Cleopatra, Leander and Aurora; Biblical names such as Catherina, Daniel and David or named after the months of the year or days of the week such as January, March, April and Saturday.

The ‘ownership’ fell into the three categories of Company slaves, private slaves and purchased slaves and there was no barrier to buying a slave from an owner at a public auction or after the death of the owner. While a slave was equivalent “to movables, gold, silver, trinkets, debits and credits”, the owner could, however, decide on emancipation or manumission through a deed as a reward for faithful service or by paying to the Poor Fund Rix 10 for release from bondage. Conditional freedom could also be won by a slave by working for a prescribed number of years in the master’s household.

The slaves’ duties were wide-ranging and onerous, says Prof. Paranavitana, with men between the ages of 20 and 60 years being considered capable of heavy work, while a majority were employed in the kitchen and lived in the master’s house with his family. They were also used to carry palanquins, as gate keepers or porters, in repair works, public works, fetching grass for stables, carrying water and firewood and for the upkeep of fortifications.

“However, the Moors and Chitties were considered foreigners and obliged to perform oeliam or compulsory services. Schweitzer in 1680 stated that he met the Ambassador Mierop on his way to Kandy at Sitavaka ‘… accompanying among other gifts …two black Persian horses covered …with green velvet and twenty falcons carried by so many black Malabarian slaves…’,” quotes Prof. Paranavitana.

While frequent instances of cruelty to slaves such as chaining, tormenting, torturing, mishandling, whipping and even murder have been recorded, there had also been a “fascinating” criminal case in 1781 in which a master had accused a Malay slave woman of murdering her own son…….. “On the day of this grisly event she (Deidamie) had taken a knife which was on the kitchen-table and driven her younger child to the outhouse where she stabbed him in the presence of her elder child. Van Cuijlenburg heard this noise and pounded on the door commanding her to open it. A Sinhalese carpenter who was nearby broke open the door. Then they found the boy lying on the floor with a stab wound on his back.”

Murder over an amulet had finally led to Deidamie being sentenced to death by strangling.

This Sunday scene has been reproduced from the ‘Early Prints of Ceylon’ by R.K. de Silva

Interestingly, Prof. Paranavitana has found in the Dutch plakkaats orders for Heathens and Muslims to give up their slaves; non-Christians being debarred from having Christian slaves; and Roman Catholics prohibited from baptizing their children and slaves.

With regard to punishment, slave-owners had been warned against meting out heavy punishments to male and female slaves without permission from officers, while a serf who engaged in adultery with a woman of free origin was liable to do public work for life. If a slave was found guilty of abusing the master’s wife or daughter, it was the ultimate punishment of the death sentence.

Finally, Prof. Paranavitana picks on the tale of Slave Island, the largest island of the Beira Lake in the days of yore where the slaves of the VOC from the Fort area were segregated at night after a slave murdered the Dutch master’s entire family.

This is how Captain Thomas Ajax Anderson of the 19th Foot Regiment in his ‘Wanderings in Ceylon’ (1819) long after the Dutch had left the shores of this country wrote:

Hence, let the eye a circuit take

Were gently sloping to the lake,

A smiling, lively scene appears,

A verdant isle, its bosom rears,

With many lovely villa grac’d

A mid embow’ring cocos plac’d!

Have once, to all but int’rest blind,

The Colonists their slaves confin’d;

But now the name alone remains,

Gone are the scourges, racks and chains!

After the passage of time, the slaves metamorphosed into coolies and then to migrant labour and indentured labour. In the modern world, the scourge of slavery has re-emerged as illegal human trafficking, adds Prof. Paranavitana.

Great civilizations rose from the blood, sweat and tears of the slaves

The word ‘slave’ derives from the ‘Slav races’ of Eastern Europe, members of which were kidnapped and sold in large numbers by merchants to the slave markets in the Moslem East in the Middle Ages, according to Prof. Paranavitana.

Explaining that most of the ancient civilizations in the near East and the Mediterranean were based on slavery, he is quick to point out that it was the blood, sweat and tears of the slaves that saw the mighty Pyramids rise up on the Eyptian skyline.

Even in the Greek state of Sparta, the majority of the inhabitants were slaves and Aristotle, the philosopher, regarded it as ‘natural’ that those barbarians should be the chattels of the Greeks. By the 17th century, slaves were a commodity open for trade and Dutch Minister Francois Valentijn in 1724 remarked that it is “…the oldest trade in the world”, adds Prof. Paranavitana.