Today’s middle class: An insight into the contemporary middle class of Sri Lanka

Introduction

Sri Lanka is a country with a population of over 20 million people. Its economy is considered as one in the stage of transforming to a middle income economy. The country has recorded on average 6.7 per cent percent of economic growth over the last decades Key macroeconomic variables have shown signs of stabilization. The country’s per-capita GDP has increased. The economy has undergone a structural transformation due to increasing importance of the tertiary sector. New job opportunities have resulted in lower rates of unemployment. Increasing incomes from migration from primary sectors to tertiary sector employment due to the growth of the services sector have resulted in higher levels of per-capita incomes. This subsequently leads to changing expenditure patterns. As a result, Sri Lankan society is experiencing a shift of the composition of social classes. This can be evident from migration of a large majority that was considered earlier as poor to the middle class although classifications based on household incomes and/or expenditure has indicated quantitative evidence for this shift. The  contemporary middle class in Sri Lanka today is diverse and its structure is complex. Further, the change in the social value system from occupation and education to consumption and possessions has indicated a hazy class structure that requires scientific exploration.Understanding the characteristics of the social dynamics that differentiate the new class and determinates of different sub-classes of it needs to be done using appropriate research methods. Thus the study conducted in Sri Lanka was with the the general objective of exploring and understanding the composite characteristics of the population that can be used to segment the society into different classes. The specific objectives were, a) identify the pattern of expenditure among the general population, b) segment the population into different classes based on expenditure definitions, and c) to identify discriminatory factors that segment the middle class into its sub-classes.

contemporary middle class in Sri Lanka today is diverse and its structure is complex. Further, the change in the social value system from occupation and education to consumption and possessions has indicated a hazy class structure that requires scientific exploration.Understanding the characteristics of the social dynamics that differentiate the new class and determinates of different sub-classes of it needs to be done using appropriate research methods. Thus the study conducted in Sri Lanka was with the the general objective of exploring and understanding the composite characteristics of the population that can be used to segment the society into different classes. The specific objectives were, a) identify the pattern of expenditure among the general population, b) segment the population into different classes based on expenditure definitions, and c) to identify discriminatory factors that segment the middle class into its sub-classes.

The conceptual framework for the study was developed through a review of literature. Thoughts of Karl Marx – class structure and system of social relations, Emile Durkheim – social morphology and classification of social types, Max Webber – types of class struggle, Talcott Parsons – Socialization, George Herbert Mead – symbolic interactionism and Pierre Bourdieu were included in the key literature used in this context.

Background

Social stratification is a key concept in sociology. This refers to the ways that the society categorizes its members into different sub-groups based on characteristics possessed by individual memb ers. Widely used characteristics in social stratification includes, income, wealth, occupation; power, and race.

Social stratification is a key concept in sociology. This refers to the ways that the society categorizes its members into different sub-groups based on characteristics possessed by individual memb ers. Widely used characteristics in social stratification includes, income, wealth, occupation; power, and race.

The concept of class in modern sociology can be traced back to Karl Marx. He asserted that the society comprises two great classes – a) the capitalist class that owned the means of production and b) the working class that possessed labour power. For Marx the lack of power of the workers was the source for the class conflict. Later Max Weber argued that class refers to economic interests. Class as asserted by Weber is a collection of individuals with comparable set of lifestyles.

Although there are large disagreements about the number of social classes and their respective characteristics, the general consensus about five broader social classes were a) upper class-elite, b) upper middle class, c) lower middle class, d) working class nd e) poor.

The simplest interpretation of the middle class is functionally the class between rich and poor or group between working and upper class. The  middle class is considered as the driving force of the economy. Adelman and Morris (1967) and Landes (1998) observed that societies with smaller middle class are generally extremely polarized and Easterly (2001) spoke of ‘middle class consensus’ which is relative equality and ethnic homogeneity in a society that facilitate economic growth by allowing society to grow on the provision of public goods critical to economic development.

middle class is considered as the driving force of the economy. Adelman and Morris (1967) and Landes (1998) observed that societies with smaller middle class are generally extremely polarized and Easterly (2001) spoke of ‘middle class consensus’ which is relative equality and ethnic homogeneity in a society that facilitate economic growth by allowing society to grow on the provision of public goods critical to economic development.

The most widely used quantitative measure to identify the membership of the middle class is based on per-capita daily expenditure. The actual values used in defining the middle class using the absolute incomes vary. Banerjee and Duflo (2008) considered middle class consumption to be between US$2 – 4 and $5 – 10, excluding outlier values. Birdsall (2007) defines a person who consumes $10 or more per day but who is below 90 per cent percentile in the income distribution as having membership in the middle class.

Easterly et al (2001) adopted a definition based on relative incomes of a society in identifying the class membership. According to them, persons included in the middle class have incomes within 2nd, 3rd and 4th quintile of the distribution of the per capita consumption expenditure of the society studied. Birdsall, Graham and Pettinato (2000) define it as an individual earning between 75 per cent and 125 per cent of the society’s median per capita income. The exact definition and thus the identification of membership in a particular society are difficult.

The Asian Development Bank considers the middle class as persons whose daily expenditure falls in the range, $2 -$20 based on 2005 purchasing Power Parity (PPP) (ADB, 2010). The ADB also estimate that almost 56 per cent of 3.4 billion people lived in Asia in 2008 belonged to the middle class and the cumulative expenditure by the Asian middle class in 2008 was $4.3 trillion. This value is expected to grow to $32 trillion by 2030. The broader middle class based on expenditure definition can also be divided into three sub-classes as a) Lower Middle Class (LMC), b) Middle Middle Class (MMC), and c) Upper Middle Class (UMC). The ADB considers persons with expenditure between $4-$10 a day as MMC, and persons with incomes less than this and those with higher than that within the broad income range of $2 – $ 20 a day as LMC and UMC respectively.

There is also a distinction between the local middle class and the global middle class. Kharas and Gertz (2010) consider households having persons whose daily expenditure ranges from $10 and $100 based on PPP terms as “global middle class”. The interest on studying the middle class arises mainly as it is considered as the “consumer class” income elasticity of demand for this segment of the society exceeds unity. The economic interpretation is that rising prices of a product would lead to increasing revenue to the supplier. The interest on tapping the middle class in export destinations and within the country through demand led growth is often highlighted in discussions on potential business growth all over the world.

According to the Household Income and Expenditure Survey conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka’s mean monthly household expenditure rose from Rs. 22,952 in 2006/07 to Rs. 31,331 in 2009/10. Average family size in 2006/07 was 4.1 and that in 2009/10 was 4.0. The size of the middle class in Sri Lanka in 2009/10 was estimated by Arunatillake (2013) as 18.5 million. 0.8 million people in Sri Lanka are considered as belonging to the global middle class.

According to the Household Income and Expenditure Survey conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka’s mean monthly household expenditure rose from Rs. 22,952 in 2006/07 to Rs. 31,331 in 2009/10. Average family size in 2006/07 was 4.1 and that in 2009/10 was 4.0. The size of the middle class in Sri Lanka in 2009/10 was estimated by Arunatillake (2013) as 18.5 million. 0.8 million people in Sri Lanka are considered as belonging to the global middle class.

Conceptual framework

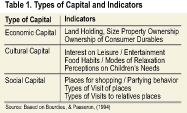

The conceptual framework of this study is based on thoughts of Pierre Bourdieu which explores the middle class in the context of three types of capital. They are a) economic capital, b) cultural capital, and c) social capital. Economic capital includes w ealth and income that can be immediately converted into money. This may be institutionalized in the form of property rights. Cultural capital is the ability to consume cultural goods and variations and educational gains. Cultural capital in certain instances is convertible into economic capital and may be institutionalized in the form of educational qualifications. The third form of capital is social capital. Contacts of a person that creates social network made up of social obligations are known as social capital. This form of capital usually is institutionalized in the form of title of nobility. Both cultural capital and social capital may be convertible in certain conditions into economic capital. The possession of three types of capital described above in the Sri Lankan context was identified using the indicators presented in Table 1.

Study Methods

The study used both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The unit of analysis is the households. A total of 1544 households representing all nine provinces were surveyed using a structured survey schedule administered by trained enumerators. Respondents answered questions about the households they belonged to. Expenditure values in local currency were converted to US$ based on the average exchange rate for the survey month. The survey schedule included questions related to household size, expenditure levels, dwelling ownership; dwelling characteristics; consumer durables and vehicles ownership and type of use; health and personal care; food habits; computers; social networking; and travel behaviour. Questions about current status and attitudes on education and attitudes about the work ethics were also included. Findings were subsequently triangulated through 36 focus group discussion sessions conducted in representative locations. The study was conducted during December 2012 and June 2013.

Membership of a household in the broader middle class was identified based on the responses recorded. Households were first identified as having membership in the middle class or otherwise based on household expenditure criteria. A household had to report daily per-capita expenditure between $2 and 20 were considered as middle class households. In the next stage, households identified as in the middle class were identified into three sub-classes based on per-capita daily expenditure thresholds. Based on the responses on expenditure questions, three sub-classes were identified as, a) the lower middle class (LMC), b) the middle-middle class (MMC) and, c) the upper middle class (UMC). The respective expenditure levels were $ 2-4, $ 4-10 and $10-20. After the inclusion into sub-classes, the possessions of socio-economic factors by households were used to understand the factors that lead to discriminating among sub-classes.

Results and discussion

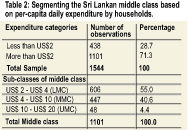

Forty-seven per cent of the respondents were males. 76 per cent of households were Sinhalese. This closely follows the ethnic and gender composition of the society studied. 88 per cent of the respondents were married and 80 per cent had children. 28 per cent of the respondents had reported per-capita daily expenditure of their respective households as less than $2 per day and subsequently were not included in the middle class. Based on reported expenditure 71 per cent of the sample were included in the middle class. Table 2 presents the sample by daily per-capita expenditure categories that served as the basis for segmentation of the Sri Lankan society into classes.

The study identified that the Lower Middle Class (LMC) is the dominant sub-class within the Sri Lankan middle class. Its share is 55 per cent of the middle class. MMC accounts for 41 per cent while the UMC accounts for a meagre 4 per cent.

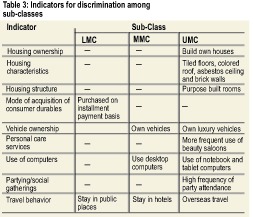

A detailed analysis of the data leads to identify discriminatory factors that are possessed by households belonging to three sub-classes within the middle class of Sri Lanka. Table 3 describes the discriminatory factors identified.

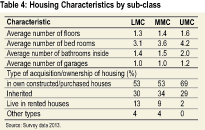

According to Table 4, all four characteristics indicate increasing average values as the sub-class standing moves upward. A typical house from the LMC has on average three rooms while a UMC house has on average, four rooms. The size of the land of the house on average is 16.6 perches. The type of acquisition of housing show significant difference among sub-classes.

Members in the UMC have a higher probability of living in a house built by them or purchasing a readymade house when compared with other sub-classes. In this regard, having tiled floors, colored roof, asbestos ceiling and brick walls are discriminatory. While all houses have reported the presence of kitchen, dining, and living rooms, the UMC members have reported having purpose built rooms such as office rooms, TV rooms, and rooms for domestic aids. The percentage of UMC households that had built their own houses was higher. About 13 per cent of households from the LMC lived in rented houses.

Ownership and acquisition of consumer durables

Possession of consumer durables is reported uniformly across all three sub-classes. Electric kettle, rice cooker, refrigerator, and gas cookers were the appliances reported by the majority of households. The type of purchase of consumer durables show discriminatory characteristic for LMC. These households have a greater probability of having acquired these appliances through installment purchases than the other two sub-classes.

Vehicle ownership and use: Approximately 75 per cent of households from the UMCs and from the MMCs own a vehicle. This percentage is higher when compared to 50 per cent of vehicle ownership reported by the LMC. Two-thirds of UMCs own luxury or semi-luxury vehicles. 39 per cent of LMC households used public transport while 56 per cent of MMC households had a motorcycle.

Cooking energy: Respondents reported that their households used firewood and LP gas as the most dominant types of cooking energy. The use of firewood is higher among the LMCs. However, more than half of LMCs, more than two thirds of MMCs and three fourth of UMCs use LP gas in their day to day cooking. Use of both LP gas and firewood for cooking is practiced across all three sub-classes and no distinction among sub-classes is observed.

Type of food: The type of foods and when it is consumed differentiates the sub-classes. The choice of fish for breakfast and dinner is more frequent among UMCs and MMCs. Less than 10 per cent of respondents reported variation in their meal plans. The practice of having pre-prepared foods of eating-out is also prevalent only among less than 10 per cent of respondents.

Health care: Three fourth of all middle class visits private hospitals. The choice of hospitals implicate less than half of UMCs, two thirds of MMCs and three fourth of LMC patronize state hospitals. Hence class distinction is subjected to the choice of sate hospitals.

Personal care services: The practice of obtaining personal care services does not show significant differences among sub-classes. Just about half of the respondents obtained the services of a salon once a month. The frequency of usage of salons by UMCs is slightly higher than the other sub-classes.

Personal care services: The practice of obtaining personal care services does not show significant differences among sub-classes. Just about half of the respondents obtained the services of a salon once a month. The frequency of usage of salons by UMCs is slightly higher than the other sub-classes.

Computer usage: The use of desktop computers and dongles is notably higher by the MMC members than the other sub-classes. This can be considered as an indicator to differentiate the sub-class as a significant proportion of LMCs believes that IT is yet a luxury. The UMCs are prominent users of laptops, I-pads and tablets. 60 per cent of MMCs reported using a desktop computer. 65 per cent of MMCs had a landline telephone and 35 per cent of them had ADSL/Broadband Access.

Banking and finances: A significantly higher proportion of UMCs and MMCs consider banks to be a tool for managing finances. The People’s Bank is used by the majority of the LMCs. Bank of Ceylon is the bank for about two-thirds of the MMCs. Subscription to insurance personal schemes is yet another indicator of UMC.

Socialization: More involvement in class based socialization in terms of frequency of parties/functions attended is evident in the UMC sub-group. 48 per cent of UMCs reported that they participate in social activities at least once in two weeks. The percentage of MMCs having this behaviour is 31 per cent and 21 per cent for the MMC and LMC respectively. This clearly indicates the differences of behaviour in UMCs with respect to the other two sub classes. Similarly style and attitude towards clothing is a clear indicator of class within middle class.

Use of media and entertainment: The readership, listenership and viewership are an indicator that subjectively differentiates the class. However, this study revels by and large; the attitude towards entertainment is relatively homogeneous with a lower distinction between UMC and MMC/LMC. 88 per cent off UMCs read newspapers while 71 per cent and 66 per cent of MMCs and LMCs respectively reported as reading newspapers. 50 per cent of UMCs watch home movies. This behaviour is considerably low among the MMCs and LMS as the values reported by the respective sub-classes are 42 per cent and 32 per cent.

Leisure and social relationships: The interpretation of leisure and places chosen vary by sub-class. This is evident through attitudes of respective sub classes. In this context interest to go out with the nuclear family is high among UMCs. The members of this social sub-class in general stay in semi luxury or luxury hotels. In contrast LMCs prefer to travel in groups.

They stay in houses of known people or in public resting places. The practice of vacations in overseas and local destinations is significant among UMCs. Visiting relatives was less frequently practiced by UMCs when compared to two other sub-classes.

Educational status and interests: The current levels of education and interest on further education clearly differentiate LMCs, MMCs and UMCs. In this regard, the attainment of education to levels of G.C.E Advanced Level or above is highest among MMCs folowed by UMCs and LMCs respectively. The language spoken at home does not clearly indicate the class distinction as a minority percentage of the UMCs primarily speaks the native language whilst a similar proportion of MMCs speaks English in their day to day activities.

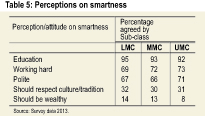

The survey also included questions about the perception on the characteristics of a smart individual. Respondents were asked to reveal their perceptions about, education, work behaviour, politeness, respect to culture and wealth. Findings are tabulated in Table 5.

The large majority of respondents from all three sub-classes indicated that education makes a person smart. Only about one-third of respondents had the perception that attitudes on respecting culture is an important determinant of smartness. Interestingly only 8 per cent of UMCs believed that wealth has something to do with smartness. However, the percentage of respondents among the LMC and MMC having this perception was higher than that of UMC.

The qualitative research design that has been used to triangulate the quantitative research identified lifestyle perspectives that implicate the emergence of LMCs into the aspired classes with the evolved status of economy. It was revealed that the majority focused on the economic achievements by way of trade, industrial or skilled employment. Those who chose education as a means of reaching the aspired class has entered the professions of high status including, medical, legal, accounting and academia and has acquired greater purchasing power. The dynamism of the evolved LMCs is such that this study recognizes them as Emerging Middle Class (EMC) a cohort which has potential to reach classes above in years to come either through wealth and/or intellectual capacity. With the increasing economic conditions the EMC can be a dominant social group of the country.

The MMCs on the other hand are being seen grouping into two segments as, a) traditional middle class (TMC), and b) the urban middle class (UMC). The former is more inclined to traditional values and are therefore keen on holding on to selected traditional values inherited from parents. They depict intellectual evolvement than material and believe in modest living with relatively lower level of conspicuous consumption. They tend to command respect in the society through an academic and professional status, establishing a cultural capital as a means of status.This segment consists of members for administrative service, and academics in state education etc than in the world of business. The rest of the MMCs have either acquired or inherited urban lifestyles and are enjoying the benefits in the contemporary world to the fullest capacity. They have greater exposure to western societies and are inclined to Sri Lankan post modernist values. Their lifestyle clearly depicts an urban Sri Lankan behaviour with heavy dependency on modern trade (supermarkets), eating out and leisure in star class hotels. This group seems to have contributed to the growth of international schools and overseas education. Some of the youth in this cohort have a lesser intention of returning to Sri Lanka as they are quite at ease in western cultures. The youth of this group of MMCs are a mix of corporate employees and entrepreneurs who are keen on excelling in chosen careers. Hence, one can see a relatively high conspicuous consumption among them in terms of vehicles, holidays, mobile communication, house ownership etc. In this context, the current study divides the MMCs into two groups, as, a) traditional middle class (TMC) and b) urban middle class (UMC) since there is a distinction between the two cohorts within the MMC even though per capita per day expenditure is somewhat similar among the cohorts.

The UMC is the minority (4 per cent) cohort of middle class in Sri Lanka, who by and large is keen on driving the economic and/or cultural capital of the country. They seem to have either inherited or acquired wealth in terms of land, property, investments, businesses, etc. Those who had inherited wealth depict relative sustainability and modesty in their outlook towards society. The cohort who had acquired wealth in the UMC seems to have driving social conformity and recognition by way of tangible acquisitions and networking. This behaviour complements the thoughts of Meads symbolic ‘interactionism’ favouring ‘me’ values over ‘I’ values. UMCs are associated with entrepreneurs who excel in business and trade and who has a greater command of purchasing power. This study identifies this cohort as MSC as it has potential to move further up by effectively using economic and social capital. There is a high chance that siblings of MSCs have the capacity to move the wealth to higher order than the parents through their networking capabilities.

Summary

The study has identified four distinctive cohorts within the middle class of Sri Lanka. They are, a) emerging middle class, b) traditional middle class, c) urban middle class, and d) middle super class. Characteristics of identified groups are consistent and can be discriminated. Of which, the emerging middle class is intriguing as it has certain characteristics similar to the middle super class. The traditional middle class indicates a greater interest towards education while the emerging middle class and middle super class are skewed towards business and entrepreneurship. The urban middle class implicates a good mix of traditional and middle super class values. The research emphasizes the proportional growing aspect of the middle class and the necessity of identifying the middle class through various types of capital, which provides a holistic approach to define the class.

References

• Asian Development Bank 2010, Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific, 4th edn, Manila, Philippines.

• Arunatilake, N 2013, How Large is the Sri Lankan Global Middle Class?, Talking Economics, http://www.sundaytimes.lk/141207/, viewed 10 August 2014,http://http://www.sundaytimes.lk/141207//talkingeconomics/2013/07/01/how-large-is-the-sri-lankan-global-middle-class/

• Birdsall, N, Graham, C,& Pettinato, S 2000, Stuck in the Tunnel: Is Globalization Muddling the Middle Class? Working Paper No. 14, The Brookings Institution Center on Social and Economic Dynamics, Washington DC.

• Bourdieu, P, & Passeron, J 1994, Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, 2nd edn, Sage, London.

• Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka, various years, Household Income and Expenditure Survey.

• Fielding, N, & Gilbert, N 2000, Understanding Social Statistics, Sage, London.

• Kharas, H, & Gertz, G 2010, ‘The New Global Middle Class: A Cross-Over from West to East’. Ch2, in Cheng Li (eds), China’s emerging middle class: Beyond economic transformation. Brookings Institute Press, Washington D.C.

• Morrison, K 2006, Marx, Durkheim, Weber: Formation of Modern Social Thought, 2nd edn, Sage, New Delhi.

• Richardson, J.E 1986, Handbook of Theory of Research for the Sociology of Education, Greenword Press, London.

• Seale, C 1998, Researching Society and Culture, Sage, London.

• Silverman, D 2004, Qualitative Research. 3rd edn, Sage, London.

| Process of study undertaken Traditional and contemporary societies are heterogeneous in social, economic and cultural aspects of its members. It is often required by academics and policy makers to identify characteristics that help identify different criteria in order to segment the society into several homogenous groups. The concept of class provides a basis to segment the society into several strata based on assets and attitudes. Middle class is generally considered as the group in between the rich and the poor. Definition of the middle class used by different researchers varies, but identifying exact characteristics of the middle class would be useful in designing social and economic policies. This study was done to identify the factors that differentiate different sub-classes of the Sri Lankan middle class. The widely accepted absolute expenditure measure of identifying the middle class and its sub-classes was used. A structured survey schedule was used to collect data from households selected randomly from different parts of the country. Data was used to identify the size of the middle class and the size of sub- classes. Factors contributing to identify the membership of each sub-class were studied through qualitative research design. |

(The writer is a well-known researcher and marketer. His research study was published during the recently concluded, professional sessions of the Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science – SLAAS, where Mr. Bamunusinghe served as a sectional President in 2013)