World War One: Those postcards to and from Hell

While sorting out some antique picture postcards recently I came across two vastly divergent examples from World War One (WW1). Almost every conceivable subject about the conflict can be found in contemporary picture postcards. My subjects, however, are confined to romance and propaganda.

Before the outbreak of WW1, the trade in picture postcards was firmly established. Thus, when hostilities began in August 1914, postcards were the perfect medium to provide a link between the servicemen, mainly soldiers fighting in the horrendous conditions of the Western Front in France, and their families, friends and lovers at home. They were postcards to and from hell.

The most striking form was silk embroidered postcards, known to collectors as “WW1 silks”, which were bought by soldiers serving on the Western Front. Local French and Belgian women embroidered the different motifs, which often featured floral designs and military insignia meaningful to the soldiers, onto strips of silk mesh. These were then sent to factories for cutting and mounting on postcards. There were two kinds of card. One had a mounted piece of embroidered silk and the other had two pieces of silk sewn and mounted to form a pocket to contain a message or a silk handkerchief. Regrettably I found no such examples.

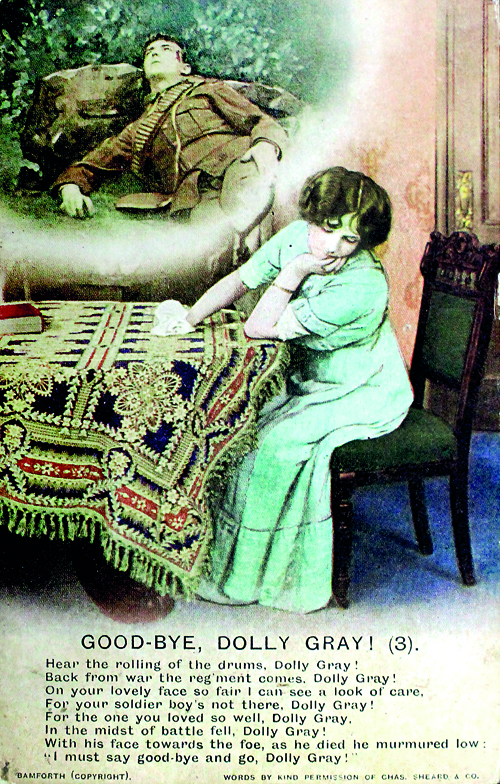

The Goodbye Dolly Gray postcard

But among the postcards in our family collection was a romantic and distinctly sentimental set titled “Songs”; the reason being that beneath the pictures of wistful, lovelorn young ladies gazing out of windows and into fireplaces is a verse from a popular song. A typical example is the music-hall piece Goodbye, Dolly Gray by Will D. Cobb (lyrics) and Paul Barnes (music), written during the Spanish-American War (1898). Of interest is that it featured in Noël Coward’s play Cavalcade (1931) and three diverse 1960s movies: David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Lewis Gilbert’s Alfie (1966) and George Roy Hills’ Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

The “Songs” set was published by Bamforth & Co. Ltd. of Holmfirth, West Yorkshire. As a film historian, Bamforth is of significance to this writer, for although the business was best known for its wide ranging postcards – including the “saucy” seaside variety – it became an early film production company as well. From 1898 to 1900 a number of short films were produced, including The Kiss in the Tunnel (1899), said to have pioneered narrative editing: in other words creating a story rather than stringing together random shots of street scenes, etc., of the genre known as “topicals”. However, production ceased until 1913 when a renaissance occurred, dozens of popular films were made, and West Yorkshire of all places had a vibrant film industry that rivalled Hollywood’s productivity until 1918 when the last film was made.

WW1 inspired many to create haunting poetry of the savagery and futility of the conflict, some of the best known exponents being Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, Robert Graves, and Rupert Brooke. On another less creative level, many servicemen wrote romantic poetry to send to their sweethearts or wives which never became public or lauded. Imagine my delight, then, when I found that four postcards in my incomplete set of 21 had hand-written verses on the reverse, all ending with “From Corporal Clayton”.

But there is a mystery, for the set belonged to Clayton as some are stamped with his name. So it looks as if the verses were never posted to the person of his desire, unless he married that person and the ones sent were combined with those without verses. If that was not the case then was he too shy? Or was the person a fiction?

The poetry appears on the first four postcards of the set, which feature those lovelorn ladies, with verses from the song mentioned earlier, Goodbye, Dolly Gray:

My heart is calling you

My dreams the whole night through are all of you

My arms are waiting and waiting to press you near

Near to the heart that is calling for love and you

Cast me not darling from thy loving heart

But keep there a corner for me

Bright eyes may grow dim, fair faces may fade

But love that’s true cannot die

the Aesop’s Fable postcard by Spanish artist Sancha

Can’t you see I am as lonely as can be?

For I want you only, there’s no one else for me

Sometimes dear I wonder why you keep away

Leaving me so lonely; lonely night and day

My heart is thine forever

Do give yours to me

We’ll lock them up together

And throw away the key

So now Corporal Clayton’s work is made public roughly a century after it was created. I hope he wouldn’t object. I just wish he was able to clear up the mystery of the verses.

********

In contrast, I also discovered two propaganda postcards by the celebrated British firm Raphael Tuck & Sons, “Art publishers to their Majesties the King and Queen”, from a series of six titled “Aesop’s Fables Up To Date”. They were created c.1917 by the Spaniard Francisco Sancha y Lengo (1874-1936), who signed his work “F. Sancha”. The postcard set was developed as a propaganda tool with German leaders inserted as fable characters. The reverse of the postcard provides a synopsis of the fable.

The postcards are from an extensive collection of sets called the Oilette Series, which was a type of card used by Tuck’s from 1903 with a surface designed to appear as a miniature oil painting. All cards in the same set had the same number (mine are both numbered 8484), and would have been issued at the same time. Early Oilettes had a brush stroke simulation, but the vast majority, like those I discovered, have a smooth surface.

The first postcard is a version of Aesop’s familiar Hare and the Tortoise fable. The picture shows a hare-like German Crown Prince Wilhelm with a satchel (or letter?) labelled “Lies” and canisters labelled “Liquid Fire”, “Poison”, and “Asphyxiating Gases” slung from its back. The hare chases the tortoise, probably a representation of a British soldier, which is laden with conventional weaponry and munitions. Allied countries are chalked on its carapace: Belgium, England, France, Russia, Italy, Serbia, Roumania (sic), Portugal, etc. The tortoise has won the race to a collection of Allied flags emblazoned with the triumphant tag, “Victory”. As the American flag is not present, this postcard was most likely issued before April 6, 1917, when America declared war on Germany.

On the reverse of the card is the statement: “Germany, after years of deliberate preparation for war, had the advantage over the Allies at first, but now that they are steadily surpassing her in the supply of munitions, it is they who are in sight of victory.”

The second postcard, described by collector Steve Shook as “incredibly stunning”, is a retelling of the Dog and the Shadow, a not so familiar Aesop fable in which a dog, carrying a piece of meat in its mouth, sees the reflection of it in some water and, snatching at the shadow, loses the meat. The picture features a wooden model of a dog – a German dachshund – complete with a Pickelhaube, a spiked helmet, with a label on its hind leg that reads, “Made in Germany”. There is a backdrop of an artillery battery with smoking barrels. Shook believes this symbolizes German industry, possibly along the River Ruhr.

As with the other postcard the dachshund is laden with bottles of “Liquid Fire”, “Poison”, and “Asphyxiating Gases”. It is standing by a pool of water and has dropped a typically fat German sausage labelled “Prosperity”. As it falls towards the water its shadow bears the message “World Dominion”. The card declares, “Germany has lost the propensity she had so laboriously acquired, in the vain endeavour to obtain the mastery of the world.”

This postcard is probably a second edition, for on the internet there is Spanish version (“Dominio del Mundo” for “World Domination”, “Prosperidad” for “Prosperity”, etc.), which was probably the work of the Spaniard Sancha. Later Tuck’s must have believed that an English translation was required.

According to the Raphael Tuck & Sons website there are four other postcards in this series: The Fox and the Grapes, The Hen that Laid the Golden Eggs, The Tortoise and the Eagle, and The Wolf and the Stork.

********

To finish, as a counterpoint to Corporal Clayton’s somewhat cloying romance I quote Siegfried Sassoon’s visceral “Suicide in the Trenches” to emphasize the hell postcards travelled to and from:

I knew a simple soldier boy

Who grinned at life in empty joy,

Slept soundly through the lonesome dark,

And whistled early with the lark.

In winter trenches, cowed and glum,

With crumps and lice and lack of rum,

He put a bullet through his brain.

No one spoke of him again.

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.