What footballers had to endure 100 years ago!

View(s):Florida, Dubai, Las Vegas are today’s Premier League footballers’ holiday destinations of choice. But 100 years ago, World War One descended across Europe, taking the sportsman of England — with varying degrees of rapidity — to the killing fields of France and Belgium.

Earlier this year a delegation of English football luminaries stood in a cold, windswept corner of northern France. They saw Lochnagar Crater where Second Lieutenant Donald Bell, a full back with Bradford Park Avenue, won his Victoria Cross.

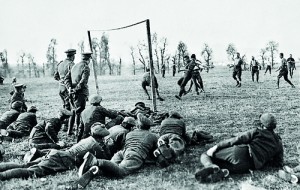

Hard life: Offices and men play a game of football during the war

He had filled his pockets with grenades and attacked an enemy machine-gun post. Writing home, he said of his deliverance: ‘I am glad I have been so fortunate for Pa’s sake, for I know he likes his lads to be top of the tree.

He used to be always on about too much play and too little work, but my athletics came in handy this trip. We are out of the trenches at present and I am perfectly fit. The only thing is I am sore at elbows and knees with crawling over limestone flints. I believe that God is watching over me and it rests with him whether I pull through or not.’

Five days after his bravery won him football’s only VC of the Great War, he undertook a similarly brave raid and died, aged 25. His letter had yet to reach England. Bell’s wife of one month, Rhoda, was presented with his medal by King George V.

But, for all its many conspicuous war heroes, football’s reluctance to stop playing as the conflict started damaged the sport’s standing in public esteem.

WG Grace: Regarded as the inventor of modern batting. Scored 1098 Test runs for England between 1880 and 1899.

The first shot of what turned into war came with the assassination in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914 of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg Empire. Yet the 38,000 spectators at the two-day Eton-Harrow cricket match were more concerned with the state of the pitch than the affairs of mainland Europe.

Soon, however, cricketers had hung up their pads to fight. A remarkable 34 first-class cricketers died during four years of fighting that started on August 4, 1914. One of those was Percy Jeeves of Warwickshire.

He was a fast-medium bowler, tipped on the evidence of just one sighting by Plum Warner — the Middlesex captain and one of the most important cricket figure of the age — as a future England player.

But it was another Plum who gave Jeeves immortality. PG Wodehouse saw Jeeves play for Hawes CC in Yorkshire and thought the name perfect for a resourceful valet, hence Jeeves and Wooster. The real Jeeves was 28 when he died at High Wood near Montauban on July 22, 1916.

FALLEN HEROES

The war also accounted for WG Grace. The most famous sportsman of Victorian England, suffered a fatal heart attack when a Zeppelin dropped a bomb on his patio in 1915.

It was Grace’s intervention, along with the heavy death toll of the Battle of Mons, that brought a cessation to the cricket season after initial opposition from government and the MCC, who decreed that ‘no good purpose can be served at the moment by cancelling matches’.

Yet the position was becoming unsustainable. Grace wrote in a letter to The Sportsman: ‘The time has arrived when the country cricket season should be closed, for it is not fitting at a time like this that able-bodied men should be playing cricket by day… I should like to see all first-class cricketers of suitable age set a good example and come to the help of their country without delay in its hours of need.’

The last first-class cricket match was played at Hove on September 2. The MCC declared ‘the continuation of cricket is hurtful to the feelings of a section of the public’.

First-class cricket resumed in 1919. By then 210 cricketers had fought, including the Indian Hardit Singh Malik, the ‘flying hobgoblin’, an Oxford golf blue, who wore his flying helmet over his turban.

The spirit that sportsman took on to the battlefield was usually inculcated in the public schools, the mood of which was summed up in Henry Newbolt’s poem: And England’s far, and Honour a name/ But the voice of a schoolboy rallies the ranks:/‘Play up! Play up! And play the game!’

In their book Public Schools and the Great War, Anthony Seldon and David Walsh tell the story of Captain Billie Neville, of the East Surrey Regiment, a former captain of hockey and cricket and head boy at Dover School, who bought four footballs for each of his platoons so they could kick their way across No Man’s Land. Neville was as relaxed about the war as he might have been about a house match.

In a letter to his parents he said: ‘As I write the shells are fairly haring over; you know one gets sort of bemused after a few million. Still, it’ll be a great experience to tell one’s children about.’ Aged just 21, he died on July 1, 1916 at Carnoy, yards in front of the German wire.

Valour took many forms. Noel Chavasse, who ran for Britain in the 400metres at White City in London’s 1908 Olympics, was the son of an Anglican bishop and graduated from Oxford. He is also one of only three men to have been awarded the VC twice — for saving lives.

‘His courage and self-sacrifice were beyond praise,’ read the citation in The London Gazette of his first VC, when he treated wounded soldiers at Guillemont in sight of the enemy.

That evening he searched No Man’s Land for four hours. The following day he rescued three people from a shell hole 25 yards from the German trenches.

As the current edition of the Olympian newsletter reports, the citation read: ‘Although he was severely wounded while carrying a wounded soldier to the dressing station, he refused to leave his post and for two days not only continued to perform his duties but went round repeatedly under heavy fire to search for and attend to the wounded.’

Thirty Scottish rugby internationals died. Rugby was responsible for founding one of the most distinguished sporting battalions, Mobbs’ Own, the idea of England back Edgar Mobbs, drawn from Northampton and Bedford. The Mobbs Memorial Match is still played to this day between the British Army and the Northampton Saints.

From other sports, Tony Wilding, the New Zealander who won the Wimbledon gentleman’s singles four times, died. Grand Prix racing driver Georges Boillot, of France, was shot down in a dogfight against five German Fokkers. He crashed near Bar-le-Duc and died of the injuries.

Football matches were played by soldiers, occasionally of opposing sides, as at Christmas in 1914, which prompted the current FA to commission a floodlit pitch to be built at Ypres. But, back home, our national sport had a mixed war. Of course many men contributed greatly to the war effort, but not immediately.

Speaking to an Army battalion, Field Marshall Lord Roberts of Kandahar summed up a growing anger at football’s slowness in abandoning its fixture list, saying: ‘I respect and honour you more than I can say. How different is your action from that of the men who can still go on with their cricket and football, as if the very existence of our nation were not at stake.’

– Courtesy Dail Mail